Italian Renaissance Art - Humanism

The philosophy of Humanism was a key element that helped to shape the artistic development of the Italian Renaissance.

ANDREA MANTEGNA (1431-1506)

'The Triumph of the Virtues - Minerva Expelling the Vices from the Garden of Virtue', 1502

(tempera on canvas)

The revival of Classical learning inspired the philosophy of Renaissance Humanism, a key element that helped to shape the intellectual and artistic development in Italy and across Europe from around 1400 to 1650. It fostered the idea that an individual’s faith was not totally governed by institutional religion, thereby freeing artists from the influence of the clergy.

While Naturalism had more influence on form in Italian Renaissance art, Humanism had more influence on its subject matter.

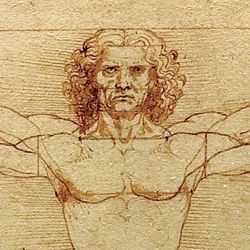

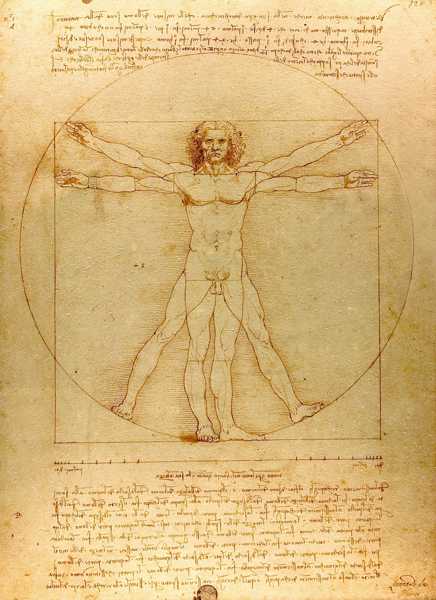

LEONARDO DA VINCI (1452-1519)

'Vitruvian Man' (c.1490)

Renaissance Humanism could be defined by Protagoras' [1] statement that 'Man is the measure of all things'. In simple terms, this meant that any individual could shape their own character and influence their own future by the way they lived their life. Humanism also placed a greater emphasis on the pleasures and social values of the here and now as opposed to the spiritual values that prepared for a better life to come.

This was the mindset that had contributed to the success of the great Classical civilizations and it was believed that its spirit could be resurrected to regenerate Italian society. A new wave of rational thought and critical analysis challenged the civil and religious authorities of the medieval Italy and revitalized both education and religion by creating a greater respect for intellectual freedom and individual expression.

Unlike later forms of Humanism, the Renaissance humanists did not deny their Christian faith. They simply wanted a more direct line to the Almighty, missing out some of the middle management of the Church. Their aim was to increase the responsibility of the individual in determining their own destiny.

Classical Subject Matter

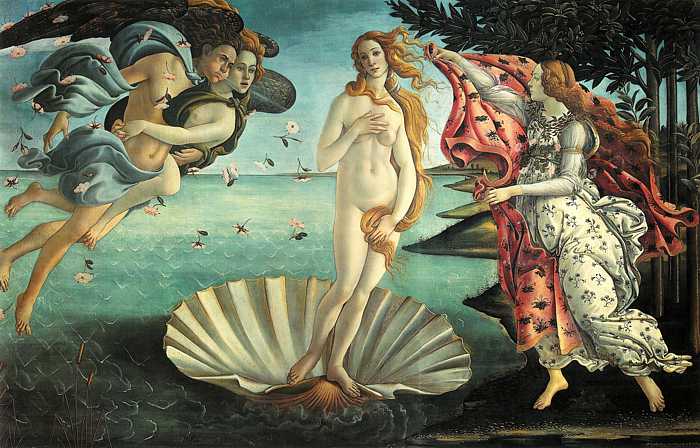

SANDRO BOTTICELLI (1445-1510)

'The Birth of Venus', 1484-86 (tempera and oil on a poplar panel)

Artistic subject matter at the start of the Early Renaissance was exclusively inspired by Christian doctrine as it was commissioned by the Catholic Church. However, as the influence of humanistic values grew, artists' focus gradually widened to include some secular subjects that were inspired by the epic tales from Classical mythology, a theme that reflected the personal interests of private patrons and collectors.

The study of Classical literature was considered to be an honorable academic pursuit among the educated and wealthy, who in turn commissioned artists to produce allegorical images based on the Greek and Roman classics. Consequently, artists who had previously been regarded as no more than craftsmen, were elevated to a similar status as scientists, writers and musicians due to the greater analytical and intellectual content of their work.

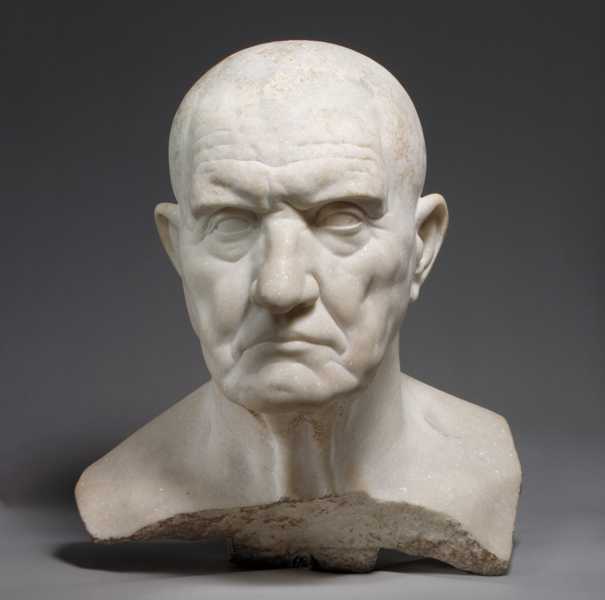

Marble Bust of a Man - An Example of Verism in Roman Art

Roman, 1st Century A.D. (marble)

© Metropolitain Museum of Art

Portraiture was another subject that emerged as a genre during the Renaissance. Very few painted portraits had survived from Antiquity so artists looked to Roman and Greek sculptures for their inspiration. Portraiture in Ancient Rome was a ‘warts and all’ realism called ‘verism’ (from the Latin word ‘verus’ meaning ‘true’) whereas Classical Greek portraiture was an idealized art searching for a perfection of the human form. Both styles were influential in the development of Renaissance portraiture.

Portraiture in Ancient Rome was a highly naturalistic art form based on humanist ideals and used to celebrate military and civic achievements or as propaganda in support of Republican values. The Romans looked on a furrowed brow or a wrinkled skin not as imperfections, but as humanistic features of distinction, a kind of facial road map of experience and wisdom that only comes with age.

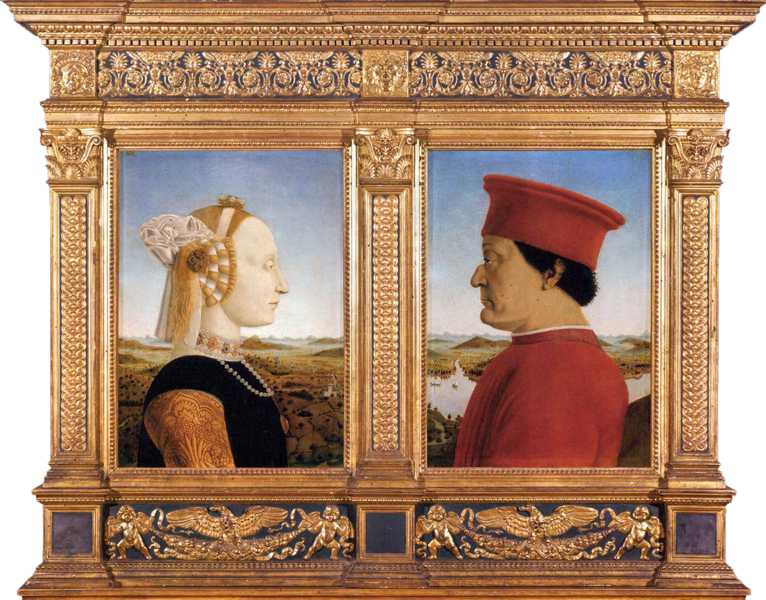

Piero della Francesca (1416-92)

'The Duke and Duchess of Urbino',

1465-66

(tempera on panel)

Some Renaissance artists, inspired by Classical humanism, adopted a Roman 'verist' approach to portraiture. In Piero della Francesca's commemorative portrait of The Duke and Duchess of Urbino (Federigo da Montefeltro and his wife Battista Sforza) the artist does not disguise Federigo's disfigured profile. This is his badge of honour, the result of an injury sustained during a tournament in which he lost his right eye and the bridge of his nose. Continuing the Classical influence, the strong profiles in this work echoes the profiles found on Antique medallions and coinage, popular among collectors at this time.

LEFT: Hellenistic Female Head, c.150 BC

RIGHT: 'La Belle Ferronière', 1490 by Leonardo da Vinci

Other Renaissance artists absorbed the influence of Classical Greek art into their portraits. Leonardo's 'La Belle Ferronière' reflects the idealized beauty of a Hellenistic carving of Aphrodite to create an image which is both introspective and graceful. The self-absorption of the subject mirrors the serenity that arises from the harmonious balance of form in Ancient Greek sculpture.

RAPHAEL (1483-1520)

'Pope Leo X with Cardinals Giulio de’Medici and Luigi de’Rossi', c. 1518

(oil on panel)

All patrons of Renaissance art, both religious and humanist, commissioned portraits. Having your portrait painted was a symbol of your power and success and a method of recording that for posterity.

Leon Battista Alberti, the architect and contemporary writer on Renaissance art, states in his essay 'On Painting' of 1435, that portraiture ‘makes the dead seem almost alive. Even after many centuries they are recognized with great pleasure and with great admiration for the painter. . . . . the face of a man who is already dead certainly lives a long life through painting.’

ANDREA MANTEGNA (1431-1506)

'Madonna della Vittoria', 1496

(tempera on canvas)

Renaissance portraiture often had a two-fold function with a built-in insurance policy against the collapse of humanist values. On one hand the ruling classes and prosperous merchants had their portraits painted to display their fame and fortune; on the other, they commissioned donor portraits as an endorsement of their religious faith. Donor portraits were paintings of the person or family who commissioned the work, usually kneeling to give thanks to a patron saint or the Holy Family. They were presented as gifts to the Church and acted both as a memorial of the donor and as a petition for prayers for their immortal soul.

Humanism may have revived during the Italian Renaissance but it never quite managed to shake off that restless need to find a meaning to life outside of ourselves.