Italian Renaissance Art - Fresco Painting

Fresco Painting is a technique that we associate with large scale murals. It is a skill that dates back to Classical Antiquity but reached its peak as an art form during the Italian Renaissance.

MICHELANGELO BUONARROTI (1475-1564)

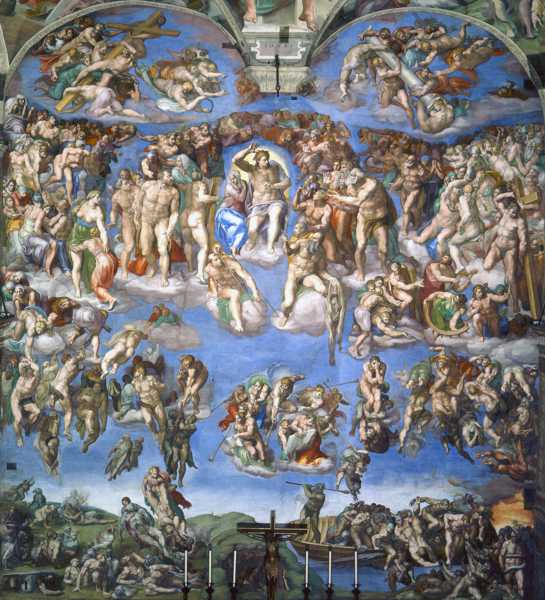

'Sistine Chapel Ceiling, 1508-12 and 'Last Judgement' 1536-41 (fresco)

Fresco Painting is a technique that we associate with large scale murals. It is a skill that dates back to Classical Antiquity but reached its peak as an art form during the Italian Renaissance. Many of the major artworks of the Early and High Renaissance were executed in fresco and are acknowledged as the pinnacle of artistic achievement. For the most part these were magnificent religious paintings that covered the walls of churches, inspiring the congregation by bringing scenes from the bible to life and creating a breathtaking atmosphere for spiritual devotion.

Fresco Painting Techniques

MICHELANGELO BUONARROTI (1475-1564)

'Delphic Sibyl' from the Sistine Chapel Ceiling, 1508 -12 (fresco)

Click the flip icon to view the Giornate

Fresco Painting is a technique that we associate with large scale murals. It is a skill that dates back to Classical Antiquity but reached its peak as an art form during the Italian Renaissance.

Buon Fresco (Italian for 'good fresco') is the most permanent method of fresco painting. It is an exceptionally difficult technique to master as you must work with confidence and speed. In fresco painting, the artist has to apply color pigment mixed with water onto a thin layer of wet plaster called the Intonaco (Italian for 'plaster'). As it dries the pigment bonds chemically with the plaster to create a durable image that lasts for centuries. Each day, an area of intonaco called a Giornata (Italian for 'a day's work') is applied to a section of the wall, which the artist must paint before it dries. There is no room for error and incomplete sections have to be cut back, re-plastered and painted again.

Fresco Secco (Italian for 'dry fresco') is a less permanent method of fresco painting where pigments are mixed with a tempera type binder and applied directly onto dry plaster. This technique has the short term advantage of producing more brilliant colors than 'buon fresco' but has a less durable finish as the paint eventually flakes off the plaster, often within the artist's lifetime.

Among the greatest examples of fresco painting during the Italian Renaissance are:

- The Sistine Chapel Ceiling and The Last Judgement by Michelangelo Buonarroti .

- The Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci in the Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan.

The former shows the art of fresco at its superlative best, while the latter displays the dangers of experimenting with a tried and trusted technique.

Michelangelo Buonarroti - The Sistine Chapel

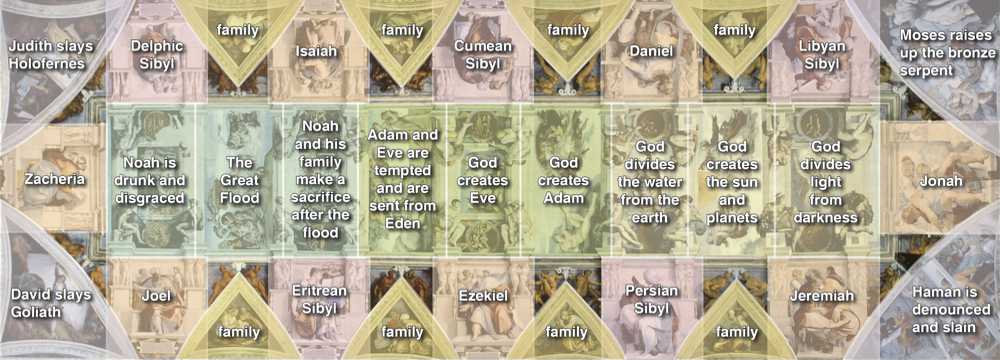

MICHELANGELO BUONARROTI (1475-1564)

'Sistine Chapel Ceiling', 1508 -12 (fresco)

Ceiling Plan © Begoon (click on flip icon to view)

In 1506, Pope Julius II first approached Michelangelo to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican. At first Michelangelo was reluctant to take on such a massive project as he saw himself principally as a sculptor and was unconvinced of his abilities as a painter. Not only was this an exceedingly ambitious commission but it was also an immensely demanding physical task. [1]

The scaffolding was eventually erected [2] and Michelangelo began the work on 10 May 1508. After as short period he dismissed his assistants and single-handedly resumed the commission to his own exacting standards. He devised an illusionistic architectural structure that framed nine central scenes from the Book of Genesis, incorporating the Creation and the Story of Noah [3]. As if the task of drawing and painting over 300 figures was not difficult enough, the inclusion of the architectural features increased Michelangelo's problems as their perspective would have to be distorted to compensate for the curve of the ceiling. Adjacent to each of the central scenes were the alternate figures of five Hebrew Prophets [4] and five Pagan Sibyls [5], each occupying their own throne. They in turn were interposed by eight ancestors of Christ [6] who were painted in trompe l'oeil lunettes. Above the throne of each prophet and sibyl sat a pair of Ignudi (idealized Classical nudes that represent angels) supporting bronze medallions strung from garlands and acorns [7]. To bracket the layout of his scheme Michelangelo painted four spandrels, one at each corner of the ceiling, illustrating dramatic stories of Old Testament heroes [8].

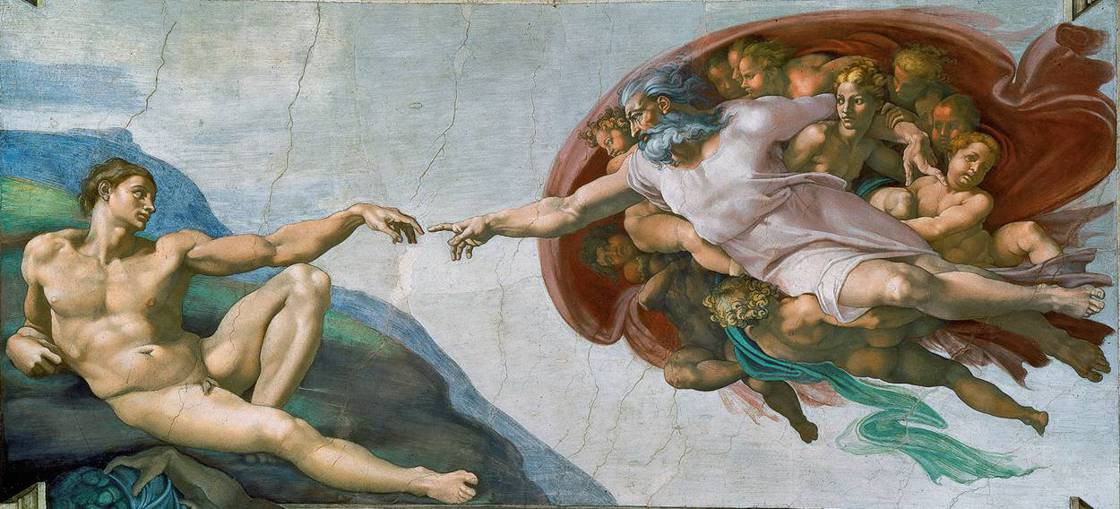

MICHELANGELO BUONARROTI (1475-1564)

'The Creation of Adam' from the Sistine Chapel Ceiling, 1508 -12 (fresco)

The most iconic image from the Sistine Chapel ceiling and also one of the most reproduced images in the history of art is 'The Creation of Adam'. It is a scene from the central vault that depicts the moment when the hand of God transmits life into the listless body of Adam. A surge of supernatural power is set to leap between God and Man as their index fingers touch in a mirrored movement which reflects the idea that 'God created man in his own image' (Genesis 1:27).

Michelangelo's God is a powerful Old Testament figure who flies around in a flurry of robes and angels. The compositional shape of this celestial group suggests the cross-section of a human brain subliminally linking the heavens to humanity.

From under the protective arm of God a gentle female figure stares directly at Adam with a greater curiosity than the other angels, who are more focused on supporting their Creator. Through that inquisitive gaze Michelangelo may be suggesting that this is the figure of Eve awaiting her own creation and thereby fulfilling the the passage from Genesis: 'So God created man in His own image; in the image of God He created him; male and female He created them.'

MICHELANGELO BUONARROTI (1475-1564)

'The Libyan Sybil' from the Sistine Chapel Ceiling, 1508 -12 (fresco)

The fact that Michelangelo saw himself primarily as a sculptor is evident in the drawing of his foreshortened figures, whose contours transcribe three dimensional form as they twist and turn through space. His fearless drawing and 'cangiantismo' rendering of form combined with an astonishing range of formidable poses demonstrate his breathtaking level of skill. The physical movement and muscularity of 'The Libyan Sybil' is a perfect example of these distinctive characteristics which were to have a major influence on the elaborate style of Mannerism.

The Last Judgement (1536-41)

MICHELANGELO BUONARROTI (1475-1564)

The 'Last Judgement', 1536-41 (fresco)

Twenty four years after the completion of the Sistine Chapel ceiling, Pope Clement VII commissioned Michelangelo to paint its 45ft. x 39ft. altar wall. According to Giorgio Vasari, the 16th century biographer of Italian Renaissance artists, Michelangelo revealed his fresco of the 'Last Judgement' on Christmas Day 1541. It was a terrifying image of damnation and resurrection that even managed to surpass the ceiling in its awesome virtuosity and the dramatic power of its narrative.

The radiant figure of a sovereign Christ holds the centre ground of the composition surrounded his apostles and the prophets. As he raises up his right arm to condemn the sinners to his left, his mother Mary recoils in fear at the thought of their eternal damnation. This is no longer the 13th century Christ of Giotto and St. Francis of Assisi who gently expressed the humility and humanity of Jesus. This is an apocalyptic and fearful Christ of fire and brimstone, who reflects the authority of the Church establishment.

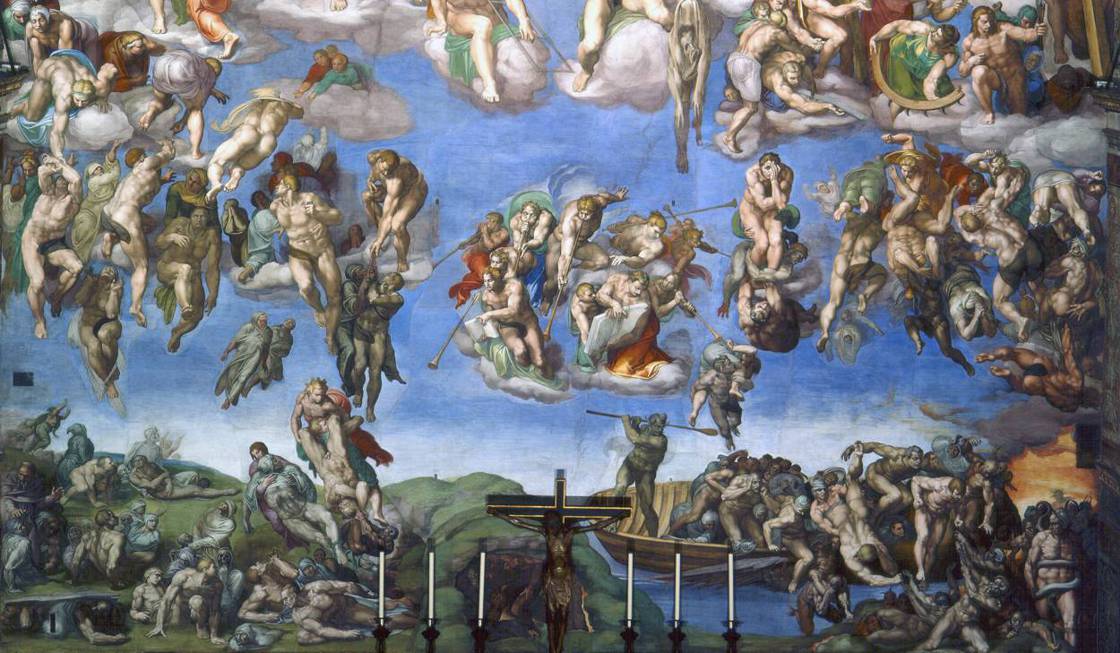

MICHELANGELO BUONARROTI (1475-1564)

Detail from the 'Last Judgement', 1536-41 (fresco)

Below the figure of Christ, the seven angels of the Apocalypse sound the call to judgement [9]. To their left as we look at the work, the saved souls ascend from their graves to their reward in heaven, although for some of them it appears to be quite a difficult climb.

To their right, the damned are dragged down by devils onto the banks of the River Styx where Charon and his demons violently herd their despairing souls towards the gates of Hell.

Even before his work was finished there were opponents to Michelangelo's vision of the 'Last Judgement'. These were mostly on the grounds of its nudity which may have been considered acceptable from the liberal standpoint of Renaissance Humanism, but against the backdrop of the Catholic Counter-Reformation many considered it inappropriate for the decoration of a church.

Pope Paul III, who continued to support the project after the death of Julius II, came to see the fresco as it approached completion. He was accompanied by Biagio da Cesena, the Papal Master of Ceremonies, and sought his opinion of the work. Da Cesena replied that it was an 'unseemly thing in such a venerable place to have painted so many nudes that so indecently display their shame and that it was not a work for a pope's chapel but rather one for baths or taverns.' [10] Michelangelo, understandably outraged at this remark, exacted his revenge on Da Cesena by painting him into the damned section of the fresco as the figure of Minos, the judge of the underworld, wrapped in his own demonic tail.

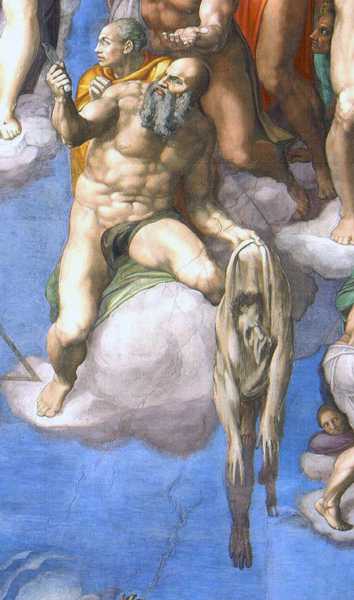

MICHELANGELO BUONARROTI (1475-1564)

Saint Bartholomew from the 'Last Judgement', 1536-41 (fresco)

However, Michelangelo's wry sense of humor was not one-sided as he also turned it on himself. Just below the figure of Christ, Saint Bartholomew can be found sitting on a cloud holding his own flayed skin (one of the legends surrounding his death was that he was skinned alive). Michelangelo, who had a deep insecurity about his own looks, painted his distorted self portrait as the face on Saint Bartholomew's sagging skin.

The year after Michelangelo died, Pope Pius IV issued instructions to paint over the more controversial areas of nudity, a job carried out by Daniele da Volterra gaining him the ignominious title of 'Il Braghetonne' (the breeches maker). Unfortunately the disapproval did not stop there as further alterations were carried out in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Despite the desecration of this masterful work, it loses none of its impact as a major work of art and continues to strike visitors today with as much astonishment as those who attended its unveiling in 1541.

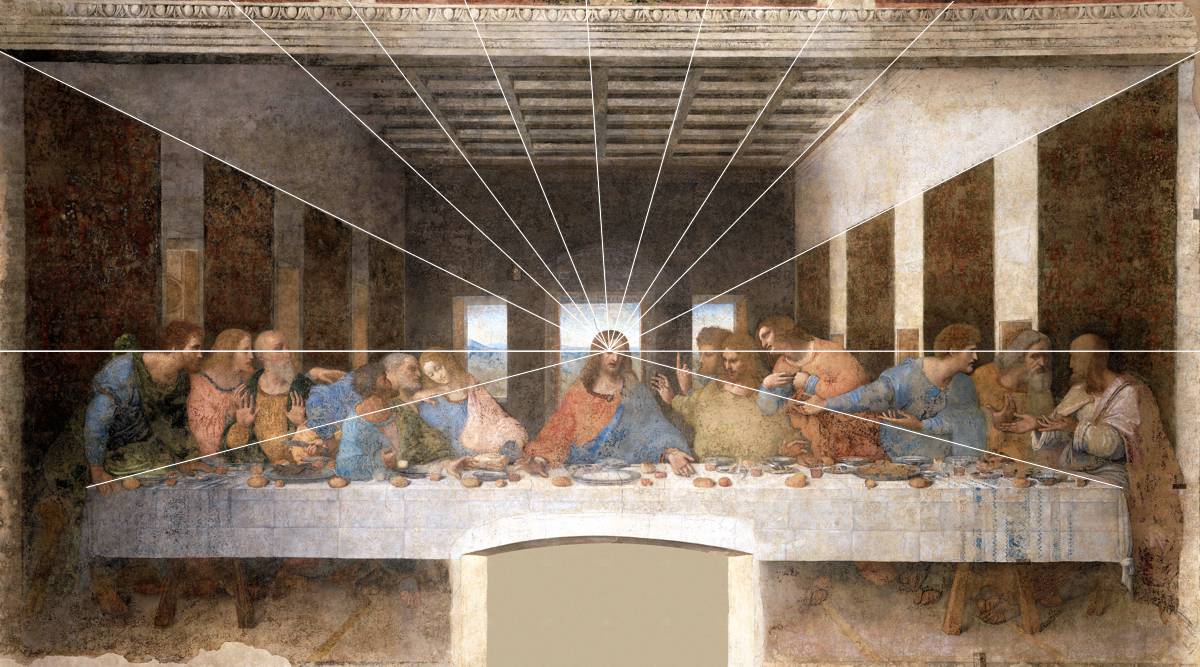

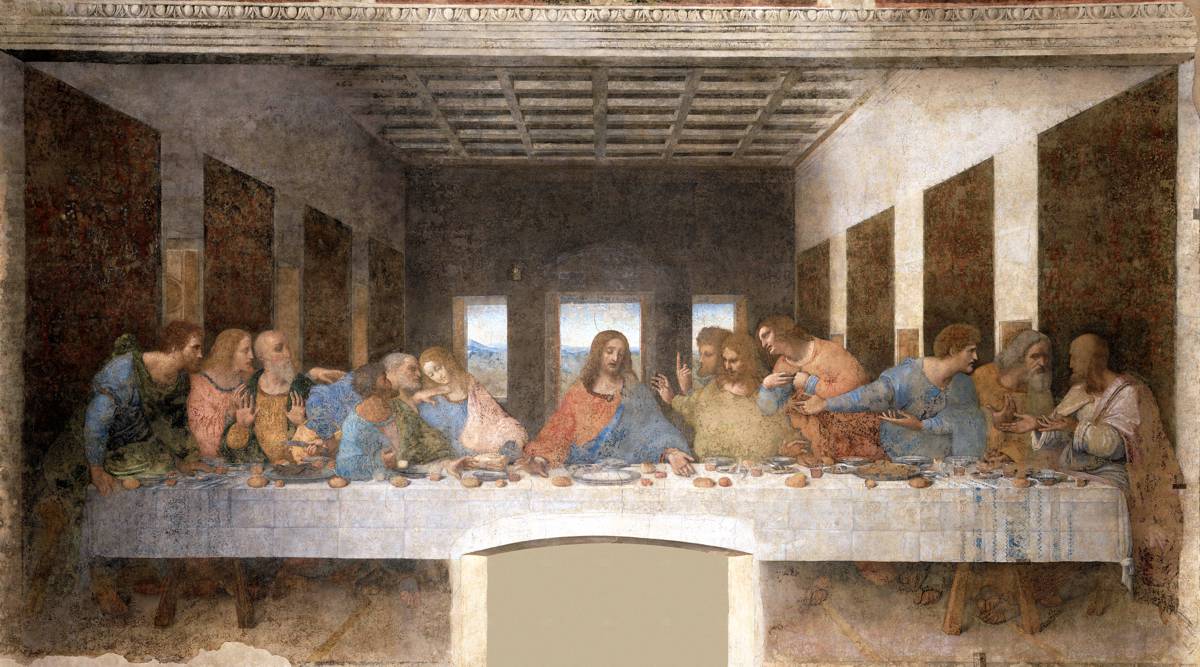

LEONARDO DA VINCI (1452-1519)

'The Last Supper', 1495-97 (tempera and oil glaze)

Click on the flip icon to view the perspective drawing.

The Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci is his largest painting and only fresco to survive. Leonardo, who personified the idea of the Renaissance man as someone accomplished in many fields, was noted for his spirit of experimentation. In this painting on the refectory wall (dining room) of the monastery of the Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, he deviated from the traditional method of fresco painting. His aim was to try to increase the strength of fresco color and tone. Instead of painting on wet plaster which forced him to work quickly, he employed an experimental 'fresco secco' technique, applying tempera with oil glazes on dry plaster. This increased the drying time of the medium which allowed him to create his characteristic blends of tone and make adjustments to his drawing. It was similar to a technique that he had used successfully on wooden panel paintings but it was not suited to the less stable surface of dry plaster. Unfortunately, the work began to deteriorate within the artist's own lifetime and what we see today is the sum of several restorations - some good and some bad. Nevertheless, 'The Last Supper' is arguably Leonardo's greatest work - an image which employs a range of visual and psychological devices that draw us into its drama:

-

Leonardo uses a dramatic one point perspective that creates a trompe l'oeil extension to the room in which it is painted. This allows us to perceive the scene as a continuation of our own space as if we are actually present at this great event. (click on the flip icon to view)

-

Leonardo uses a light source from the left which corresponds to the natural window light in the room reinforcing the reality of the scene.

-

Leonardo uses a vocabulary of body language in his figures who are responding to the psychological shock of Jesus' dramatic statement, 'Truly, I say to you, one of you will betray me.' They display a full range of emotions from surprise, disbelief, concern, sadness, fear and indignation.

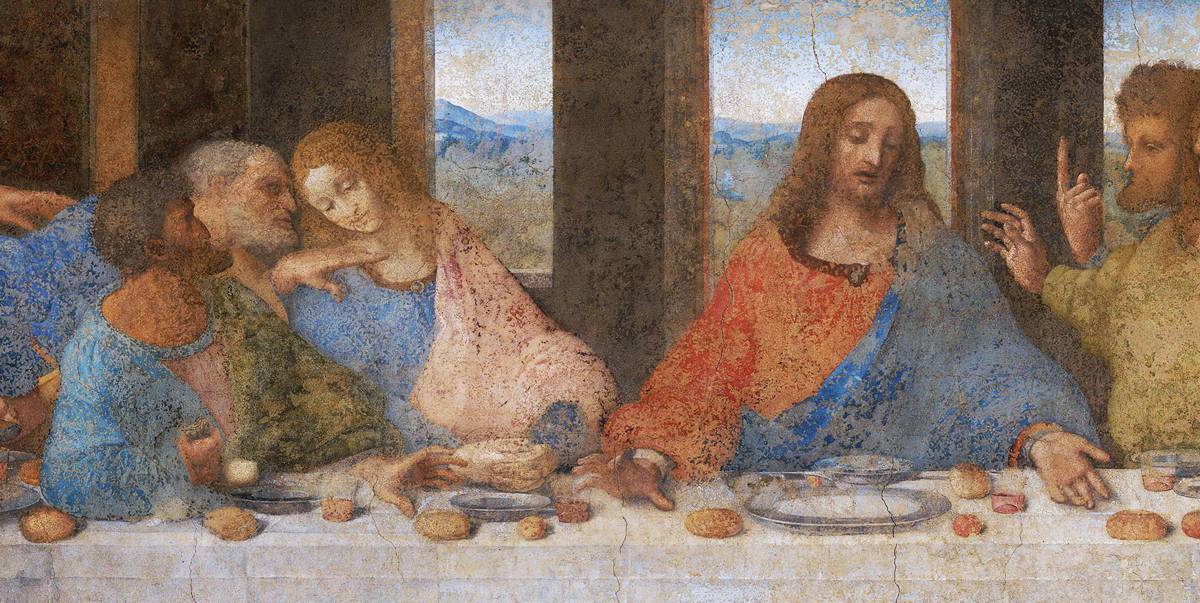

LEONARDO DA VINCI (1452-1519)

Detail of Judas, Peter and John from 'The Last Supper', 1495-97 (tempera and oil glaze)

Leonardo's version of 'The Last Supper' was the first painting of this subject where Judas sits among the other apostles. In previous versions by other artists, Judas traditionally sat alone on the near side of the table so that he could be easily identified by the viewer. There is no need for that here as Leonardo constructs a symbolic and psychological profile of Judas that leaves you in no doubt as to his identity:

- Judas has the lowest eye-level in the painting reflecting his low moral status.

- His shaded form contrasts with the lighter figures of the other apostles using the symbolic associations of light and dark as an indication of virtue or the lack of it.

- Judas draws back in a physical reaction to his guilt when he hears Christ's statement and accidentally spills the salt cellar, a symbol of his betrayal. [11]

- His clenched fist grasps a purse, the unmistakable attribute of his treachery.

Leonardo possessed an unrivalled knowledge and understanding of human anatomy, combined with a peerless painting technique, which enabled him to create perceptive portraits and compositions with an intellectual and psychological depth that was entirely new to art.