Paintings by Giotto

Giotto di Bondone was the most influential artist of the Early Renaissance in Italy. His paintings revived the naturalism of classical art which had been lost to the symbolism and superstition of the Dark and Middle Ages. He paved the way to a more realistic style of art, based on observational drawing, that flourished in the hands of Renaissance masters from Masaccio to Michelangelo.

GIOTTO (c.1267-1337)

'The Scrovegni (Arena) Chapel Frescoes', (1304-1306)

Giotto di Bondone was the most influential artist of the Early Renaissance in Italy. His paintings revived the naturalism of classical art which had been lost to the more decorative styles of the Middle Ages. Giotto drew his subjects from life which gave them a greater degree of naturalism, and his figures have a powerful emotional presence that was communicated through their body language and expressive features. Giotto's naturalism was not realism as we understand it today, but a style that was stripped down to its basic compositional elements of form, space, movement and balance, enhanced by emotive gestures and glances which combine to communicate a strong dramatic narrative.

It is generally agreed that much of the information we have on Giotto contains more fiction than fact, both of which come from the writings of Giorgio Vasari, the 16th century biographer of Italian artists. Vasari states that Giotto came from a humble farming community in Colle di Vespignano, a small village in the Florentine countryside. As a young boy about the age of ten, his father put him to work shepherding a few sheep. While they were grazing, Giotto would often pass the time by sketching on flat stones. One day, the artist Cimabue (c.1240-1302) was walking in the fields and came upon the boy who was scratching the image of a sheep onto a stone. He was so impressed by the accuracy of Giotto's drawing that he approached his father for permission to take him to Florence to work as one of his apprentices.

Giotto's apprenticeship in Cimabue's workshop would have lasted around a decade, in which time he would have been trained in the techniques of his craft: grinding pigments, preparing panels for painting, copying examples of artworks, and ultimately assisting his master by painting the background areas and the less important figures of a commission.

Artists at this time, unlike the celebrities of today, were thought of as humble artisans and not worthy of note. They were skilled craftsmen who neither signed their work nor viewed fame as an indicator of success. Any accolades they were due went to enhance the honour of their patron, the artistic grandeur of the setting, or the prestige of their workshop.

Giotto: The Revival of Realism

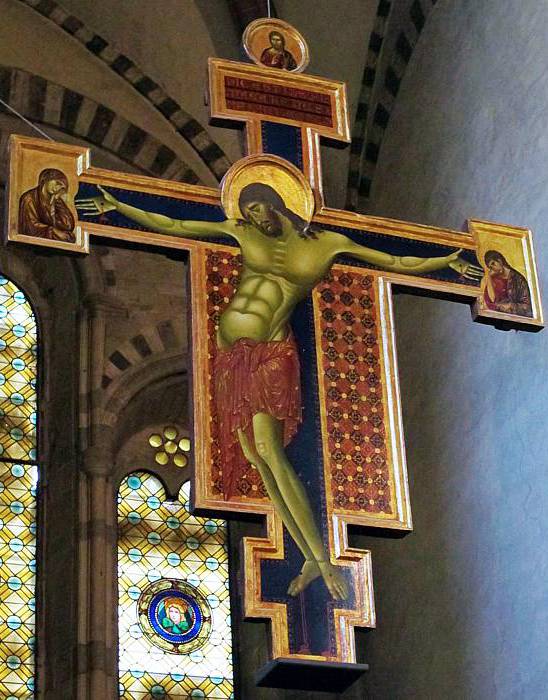

CIMABUE (c.1240-1302)

Crucifix from the Basilica of San Domenico, (1267–71)

On trip to Rome in 1272, Cimabue was inspired by the naturalism he saw in Roman and Greek antiquities. As a result, he became the first artist of the Early Renaissance to move away from the rigid traditions of the Byzantine style by enhancing the realism of his subject matter. Around 1285 Giotto followed in his master's footsteps to Rome where he was influenced by the frescoes and mosaics of the Roman artist Pietro Cavallini (c.1259-1330), whose natural rendering of form continued to challenge the conventions of Byzantine art. Giotto soon absorbed the ideas and techniques of both these masters but took them to a new level of realism.

This heightened level of realism is clearly illustrated when we compare Cimabue's Crucifix from the Basilica of San Domenico in Arezzo with Giotto's Crucifix from the Basilica of Santa Maria Novella in Florence.

The figure of Christ in Cimabue's work has a stylized form which is elegantly displayed against the backdrop of a cross. This is an idealized image that is designed to communicate a moving but refined version of Christ's passion and death.

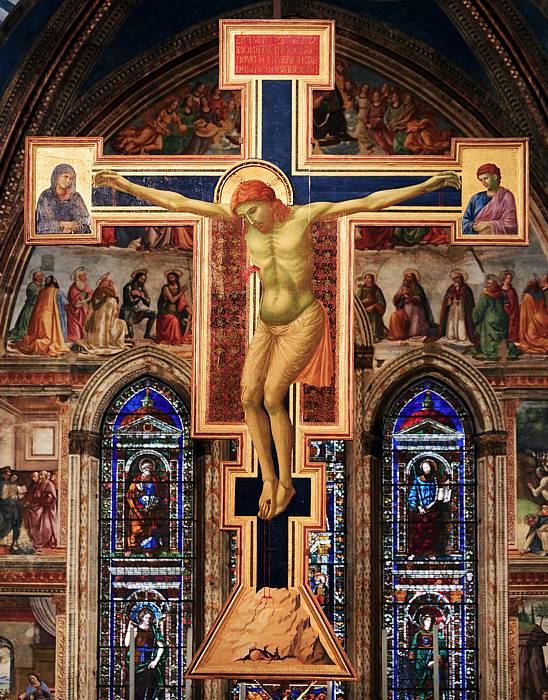

GIOTTO (c.1267-1337)

Crucifix from the Basilica of Santa Maria Novella, (1290-1300.)

In Giotto's crucifixion we feel the full and painful weight of Christ's body as he strains against its slow and agonizing collapse. The gravitational pull of his crucified form converges on the single nail that pins his feet to the cross. This is a radical departure from the separate nailing of each foot in traditional Byzantine art.

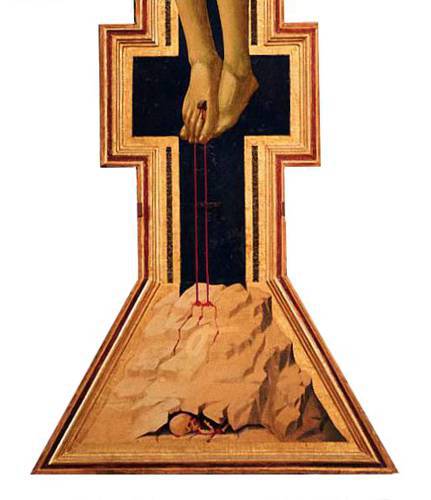

Detail of Giotto's Crucifix from the Basilica of Santa Maria Novella.

The blood that flows from Christ's feet is absorbed by the mound of earth and small skull in the trapezoid at the bottom of the cross. This shape represents 'Golgotha' which means 'the place of the skull', the site where Jesus was crucified (and according to the legend from the Greek theologian Origen, where the bones of Adam were buried). Giotto uses this story as a metaphor for redemption where Christ's blood washes away the sins of man, symbolized by the remains of Adam. His version is a more naturalistic attempt to portray both the raw humanity and the redemptive sacrifice of Christ's passion.

Frescoes in The Basilica of Saint Francis of Assisi. (1297-1300)

Giotto lived in an era when attitudes to art and religion were changing. The teaching of Saint Francis of Assisi, with its focus on the humanity of Christ and care for the poor, was growing in popularity. It generated a shift of emphasis where a reverence for the Majestic Christ of the Byzantine era was eclipsed by a faith in the living Christ of the ‘Sermon on the Mount’, where he blessed ‘the meek, the merciful, the poor and the peacemakers’ (Matthew 5-7).

This change of emphasis was also reflected in Giotto's art. Just as Saint Francis' piety was based on a 'spirituality of subtraction', where he renounced his worldly goods to deepen his commitment to God, Giotto renounced the flat, decorative formats of Byzantine art in favour of a naturalism based on observational drawing. This, in turn, led to the introduction of equally lifelike backgrounds that enhanced the depth of the picture plane and offered his figures the possibility of a narrative context.

The first three panels of the Life of Saint Francis in the Upper Church in Assisi.

He had the unique skill of being able to condense the essence of a story into a few simple images that brought the Bible to life. For the first time in the history of art, the illusionistic realism of Giotto's work allowed the spectator to inhabit a Biblical scene and thereby personalize their appreciation of its unfolding drama. No longer was it necessary to decode the stylization of an artwork to access its mystery. The economy of Giotto's space left emotional room for the spectator to participate in the scene, bringing them closer to the sacred and the sacred closer to them.

In 1296 Giotto was commissioned to paint a cycle of twenty-eight frescoes on 'The Life of Saint Francis' in the Upper Church in Assisi, the town where the saint was born and died. Each panel was illustrated with an episode from the 'Major Legend', a biography of Francis written by Saint Bonaventure. The paintings are arranged thematically around the lower section of the walls, each separated from the next by a trompe l'oeil column, forming a line of windows that look into his life. The figures are placed parallel to the picture plane and close to the front of each panel, moving from scene to scene along the wall with the clarity of a cartoon strip. The realism of Giotto's art encourages the spectator to imaginatively enter each scene, helping to direct and deepen their meditation. His compositions invite this level of interaction through their revolutionary arrangement of space, the scale and movement of their figures, and their use of local architecture for the backgrounds.

There is some confusion as to what panels were executed by Giotto himself and what parts were painted by other artists, as the Franciscan monastery records were destroyed in 1897 by Napoleon's troops who used the Upper Church as a stable for their horses. Some authorities have contested the attribution of these frescoes due to inconsistencies in their style; others have put it down to changes in the development of Giotto's style due to the maturing influences he absorbed from his repeated trips to Rome. However, in the light of their accomplished drawing and composition, most agree that Giotto worked on at least the first ten panels.

Giotto: The Basilica of Saint Francis Panel 1 - Homage of a Simple Man

GIOTTO (c.1267-1337)

'Homage of a Simple Man', 1297-99 (fresco)

The first panel from 'The Life of Saint Francis' is titled 'Homage of a Simple Man'. It tells the story of a poor man with learning difficulties who instinctively recognizes the good in Francis, and whenever he met him would lay his cloak at his feet as a sign of reverence. Francis makes a point of acknowledging the man's gesture and by doing so endorses his dignity as a brother in Christ. As always, he is teaching by example as contemporary society, represented by the quizzical attitude of the other figures, would not have accorded such respect to a poor or disabled individual.

Giotto cleverly uses the columns of the 'Temple of Minerva' (an ancient Roman building in Assisi that was used as a courtroom and jail in Giotto's time) to pace out the steps between Francis and the kneeling man, metaphorically closing the gap between them. The adjacent 'Tower of the People' on the left helps to confirm the date the work as it is missing its battlements which were not completed until 1305.

Although this is the first panel of the series, it was the last to be painted, probably due to the awkwardness of the architrave projecting from the wall.

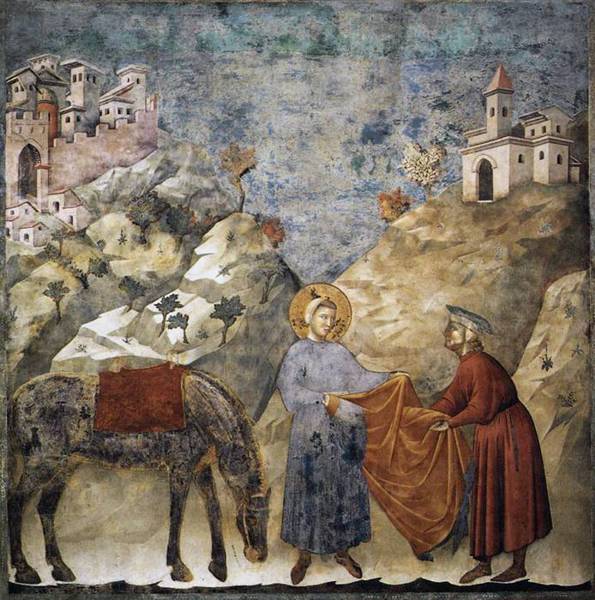

Giotto: The Basilica of Saint Francis Panel 2 - St Francis Giving his Cloak to a Poor Man

GIOTTO (c.1267-1337)

'St Francis Giving his Cloak to a Poor Man', 1297-99 (fresco)

In the second panel, titled ‘Saint Francis Giving his Mantle to a Poor Man’, he meets a knight who has fallen on hard times. This is illustrated by the man's lack of a surcoat, the outer garment that a knight wore over his clothes as a symbol of his nobility. Francis, who came from a wealthy background himself, understands the embarrassment of this man's descent into poverty and takes pity on him. He takes off his own cloak and gives it to the knight to cover his humiliation.

The scene takes place in front of two rocky hills, on whose peaks two different types of architecture represent the materialistic and the spiritual world - the world of the city on the left and the world of the cloister on the right. Their positioning is significant in biblical symbolism, “A wise man’s heart directs him toward the right, but the foolish man’s heart directs him toward the left.” (Ecclesiastes 10:2). The descending slopes lead down to the figure of the saint who is facing the monastery, indicating that he will turn away from his privileged life in the city and choose to lead a secluded life of poverty.

It is no coincidence that this and the previous fresco sit side by side. They are both non-judgemental responses to poverty irrespective of its cause: the first shows an empathy with those who are blamelessly and congenitally poor and the second is a compassionate understanding towards those who, for whatever reason, have descended into poverty.

Giotto: The Basilica of Saint Francis Panel 6 - The Dream of Pope Innocent III

GIOTTO (c.1267-1337)

'St Francis Giving his Cloak to a Poor Man', 1297-99 (fresco)

In the sixth panel of the series, titled 'The Dream of Pope Innocent III', we see Francis dressed in the clothes of his religious order which are still worn by his clergy today. His habit is brown, a humble earth color chosen to symbolise his abstinence from the gaudy distractions of the world. The cord around his waist, which substitutes for a belt, has three knots tied in it to represent his vows of poverty, chastity and obedience. In Francis' time, a belt was used to carry your money pouch and your sword, so in compliance with the Franciscan rule that they should live 'without property', the wearing of a simple white cord was a sign that you were a man of God who possessed neither.

On the right-hand side of the painting, Pope Innocent III is asleep in a ridiculously opulent four poster bed with two attendants dozing at his bedside. The left-hand side of the painting illustrates his dream where Francis supports the Basilica of Saint John Lateran which is about to topple over. This basilica was the official residence of the Pope and the seat of government of the Catholic Church from around 324 until 1309. When Francis requested authorisation to establish a new religious order, the Pope interpreted his dream as a sign that this poor friar had been chosen by God to support the papacy and reform the Catholic Church. As a result, the Order of Friars Minor (O.F.M.), which consisted of Francis and eleven more friars was officially approved in 1209. Today they are more commonly known as the Franciscans.

Giotto employs two clever compositional devices to animate the swaying church. First, he uses the bounce of the inverted arches on the canopy of the Pope's bed to amplify the precarious threat of the falling tower. Secondly, he links each side of the painting by echoing the sway of the tower with the arc of the curtain on the four poster and the strong white curve of the Pope's nightshirt, both of which act as visual shock absorbers to the pitching basilica.

The mathematical technique of perspective in the painting has not yet fully developed, and would not be perfected for another 140 years, but Giotto still manages to capture the three-dimensional qualities of the architecture with an intuitive understanding based on his observation. When you consider the technical difficulties of painting in fresco, the details of the buildings and their interior decoration are both meticulous and magnificent. If by any chance you have visited Rome and are thinking that the Lateran Basilica looks nothing like the building that Francis is supporting, the original church was destroyed and rebuilt after two fires in 1307 and 1361.

Giotto: The Scrovegni Chapel (Arena Chapel), Padua

GIOTTO (c.1267-1337)

'The Scrovegni Chapel', 1304-06

The West Wall Entrance with 'The Last Judgement'.

The Scrovegni Chapel in Padua is Giotto's masterpiece and one of the supreme monuments of Western Art. It is also known as the Arena Chapel as it was erected next to the site of an ancient Roman amphitheatre. This small private church was built by Enrico Scrovegni in atonement for the sins of his family. Both Enrico and his father, Reginaldo, were usurers (14th century money lenders), a heretical practice that was condemned by the Church as the exploitation of the poor. By virtue of his occupation, Reginaldo was portrayed in Dante's 'Inferno' [1] as a suffering sinner condemned to the inner ring of the Seventh Circle of Hell. In fear for his immortal soul, the Scrovegni Chapel served as Enrico's insurance policy against the fires of Hell.

GIOTTO (c.1267-1337)

Enrico Scrovegni Presents a Model of the Chapel to the Virgin Mary.

Detail from 'The Last Judgement'

1304-06 (fresco)

Enrico, himself, is depicted in the fresco of the Last Judgement personally pleading his case. He is optimistically placed on the side of the saved souls, presenting a model of his Chapel to the Virgin Mary, Mary the sister of Martha and Lazarus, and Mary Magdalene [2], asking for their intercession.

GIOTTO (c.1267-1337)

'The Scrovegni Chapel', 1304-06

The East Wall Altar.

Enrico commissioned Giotto, the greatest artist of the day, to decorate the interior of the Arena Chapel. Giotto devised a cycle of thirty-nine frescoes on three levels that sequentially documented the life of Christ. The narrative starts with the story of the Virgin's parents, Joachim and Anna, and chronologically follows the Life of the Virgin herself, the Life, Passion, Death and Resurrection of Jesus, finishing with the fearful Last Judgement. It was customary in medieval churches that the Last Judgement was painted on the west wall, which was traditionally the back of the church, so that the congregation would see the image on leaving. If you were not spiritually transformed by the sacred liturgy and inspirational artwork, you would certainly reconsider your theological stance when you turned to leave the church and were confronted by the devil and his demons feeding on the damned. This was the late Middle Ages where a theology of fear operated as the ultimate incentive for repentance.

Giotto: The Scrovegni Chapel - The Last Judgement (1304-06)

GIOTTO (c.1267-1337)

'The Last Judgement', 1304-06 (fresco)

GIOTTO (c.1267-1337)

Detail of the Saved Souls from 'The Last Judgement' (1304-06)

GIOTTO (c.1267-1337)

Detail of the Damned from 'The Last Judgement' (1304-06)

Giotto's fresco of the 'Last Judgement', which is said to be a source of inspiration for Dante Alighieri's 'Divine Comedy', covers the entire west wall above the entrance to the church. It is the largest painting in the building measuring approximately 33ft high by 28ft wide. Its composition is horizontally split into an upper and lower level by the cross-section of a floor which separates the spiritual realm of heaven from the terrors of hell.

The upper level is divided symmetrically by the figure of Christ, who is framed by a rainbow-colored aureole. His radiant aura is encircled by angels, four of which are sounding trumpets to announce his presence. Christ is by far the largest figure in the painting, signifying his omnipotence as the Supreme Being. To his right and left we have a mirror image of the twelve apostles who sit on their thrones overseeing this apocalyptic event. There are six on each side, with Matthias replacing Judas Iscariot, the apostle who betrayed Jesus. Above them are legions of angels in serried ranks, the front row of which are gradually rolling back the sky like a theatrical curtain to reveal the gateway to heaven.

The lower level is split into two halves representing the saved ascending to Heaven on Christ's right, and the damned descending into Hell on his left. An empty cross, a symbol of Christ's redemption, is supported by the archangels Michael and Raphael, marking the borderline between the two groups. Above the cross, Christ welcomes the redeemed souls and invites them to join him in Paradise. Some are still rising naked from their graves while others, who are already clothed, and are being shepherded by angels towards their Heavenly reward.

GIOTTO (c.1267-1337)

Portraits of Giotto and Dante from 'The Last Judgement'.

Among this latter group we can see the image of Giotto himself. He is fourth from the left on the first row wearing a white hat. This is the only self-portrait by the artist that we know of. Directly behind him stands his friend, the poet Dante Alighieri, who wears a laurel wreath on his head, a symbol of his distinction as a poet. Beneath the cross, Enrico Scrovegni humbly kneels to present the church to the Blessed Virgin in restitution for his sins.

In a single movement, Christ turns to greet the faithful with his open right hand, and simultaneously banishes the unfaithful with a sweep of his left hand. Flames start to ignite at the bottom of the aureole, building in heat and ferocity to form a river of fire that flows and propels the lost souls to their horrific fate in the blistering hot caverns of Hell. Satan, a bloodless blue horned devil, sits upon a flesh-eating dragon, pulling the condemned from their graves and gruesomely devouring and defecating their flesh. Those not suffering this torment are being tortured by his demonic acolytes who inflict an endless variety of obscene persecutions. The figure of Judas, who is missing from the ranks of the apostles, can be seen hanging on the left-hand side of our 'Detail of the Damned', but also appears on the right-hand side receiving a bag containing his thirty pieces of silver, the price he was paid for his betrayal.

Giotto's 'Last Judgement', like most depictions of the theme from the Middle Ages, is an image of social control. It depicts a reward-punishment system that is designed to modify your behaviour through fear. It is an example of institutional moralism in preference to humanizing mercy. In 2015 Pope Francis said, “How much wrong we do to God and his grace when we speak of sins being punished by his judgment before we speak of their being forgiven by his mercy. We have to put mercy before judgement,....”. There is great compassion in the words of Pope Francis which advocates restorative justice in preference to our history of retributive justice. They reflect the kind of world we aspire to but alas, they don't inspire the sensational imagery of our punitive past.

Giotto: The Scrovegni Chapel - The Flight into Egypt (1304-06)

GIOTTO (c.1267-1337)

'The Flight into Egypt', 1304-06 (fresco)

Despite the impressive scale, dramatic narrative, and complex arrangement of 'The Last Judgement', Giotto's best work is found in the smaller panels that depict the 'Life, Passion, Death and Resurrection of Jesus'. Their simple figures, whose body language, eye contact, and naturalistic appearance communicate intimate moments of human relationship, became the basic model for figure composition in Western Art for centuries to come.

'The Flight into Egypt', which illustrates the Holy Family's escape from Herod's 'Massacre of the Innocents', is painted in a naturalistic style that had not been seen in art for a thousand years. Giotto devises creative compositional techniques to tell a simple story that is accessible to all. He uses the eye contact between individual characters to supply a subtext to the story and the relationship between his figures and their background is designed to strengthen elements of that narrative.

Mary sits upright on the donkey focused on the pitfalls ahead, symbolised by the precipitous edge to their narrow path. The infant Jesus looks over her shoulder, providing a visual link to the group at the rear. Joseph who is apparently leading the group turns around to talk to his son, his line of sight deflected from the path ahead pulling our attention back into the picture. The angel above his head, who is guiding the group, is looking at Mary and pointing to indicate that they are travelling in the right direction. The group at the rear are also making eye contact with one another which enhances their interaction and implies their ongoing conversation as they progress on their journey.

The strong triangular shape of Mary and Jesus is echoed in the form of the mountain behind them, a symbol of stability that emphasises her resolve to protect the infant Jesus. Its outline also provides a visual link from the head of Saint Joseph at the front, to Salome the midwife and his other two sons at the rear of the group. The flow of this line continues through the arm and hand of one son, along the rear harness of the donkey, up through Mary's knee to the donkey's mane, and back to Joseph to complete a loop that unites the entire group.

Giotto: The Scrovegni Chapel - Fresco Painting Techniques

GIOTTO (c.1267-1337)

Fresco Painting Techniques

Giotto uses two fresco techniques for his paintings in the Arena Chapel. Most if them are entirely painted in buon fresco, where the artist applies a mixture of pigments and water directly onto a section of wet plaster. The color bonds with the plaster to become a permanent part of the wall and is as durable as the wall itself. However, one of the disadvantages of buon fresco is that the intensity of the color pigment is slightly diminished when it bonds with the plaster. Enrico wished to avoid this happening to the lapis lazuli blue color that was used for the robes of the most important figures. He saw no point in using an exceptionally expensive pigment and reducing its intensity with the buon fresco technique, so he asked Giotto to paint these blue sections in fresco secco, a type of tempera painting onto dry plaster that retained a greater brilliance of color. Unfortunately, fresco secco is a less durable finish as over time the paint flakes off the plaster. This effect can be seen on the robes of Mary in 'The Flight into Egypt' as only a couple of patches of the original lapis lazuli pigment remain. It is fortunate that Giotto had underpainted her robes in buon fresco to maintain the tonal integrity of the image.

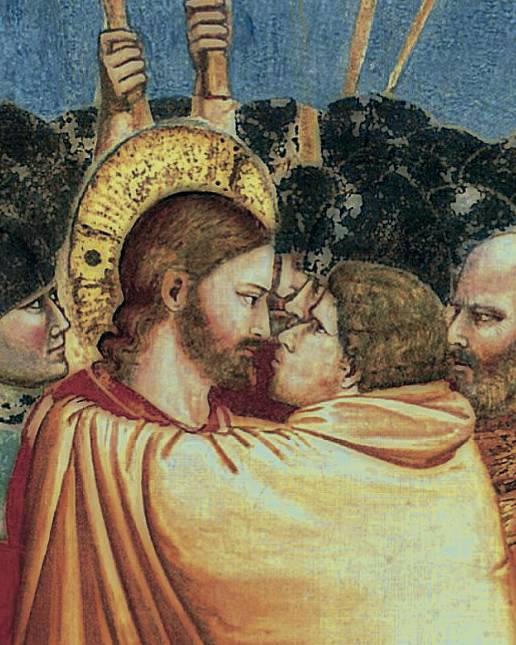

Giotto: The Scrovegni Chapel - The Betrayal of Christ (1304-06)

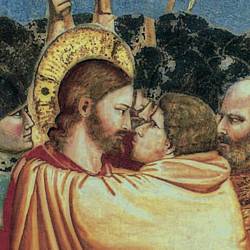

GIOTTO (c.1267-1337)

'The Betrayal of Christ', 1304-06 (fresco)

In his dramatic fresco of 'The Betrayal of Christ', Giotto portrays a confrontation between truth and falsehood as the innocent gaze of Jesus meets the guilty eyes of Judas Iscariot. After The Last Supper, Jesus and his disciples went to the Garden of Gethsemane to pray, when Judas arrived with a crowd armed with clubs and swords and supported by a group of Roman soldiers to add some legal status to their treachery. They were sent by Caiaphas and the elders who had conspired to arrest Jesus and have him put to death. Caiaphas, the high priest, had bribed Judas with '30 pieces of silver' (the traditional compensation payment for the loss of a slave) to identify and hand Jesus over to the armed assembly. Judas, with a callous hypocrisy, arranged to betray Jesus with the sign of a kiss: "The man I kiss is the one you want. Arrest him!" (Matthew 26:48).

GIOTTO (c.1267-1337)

Detail from 'The Betrayal of Christ' (1304-06)

Giotto depicts the moment just before the traitor's kiss where Jesus looks into Judas' eyes and says, "Be quick about it, friend!", letting him know that he sees through his deceit. The psychological drama of the moment is created by their face-to-face meeting as the calm acceptance of Jesus encounters the cunning pretence of Judas. The entire composition of the painting is designed to lead you to this face-off. The movement of figures either side of Jesus draws you towards the heart of the conflict as the mob drives forward to surround and isolate him from his companions. However, there is one exception to this. One of the high priests, who recognises the righteousness of Jesus, steps into the foreground and signals his hesitancy to go through with this deceitful conspiracy. His movement is counterbalanced on the left-hand side by an elder trying to restrain Saint Peter who has retaliated against the arrest by cutting off the ear of Malchus, the High Priests servant.

GIOTTO (c.1267-1337)

Examples of recurring portraits drawn from life.

Giotto's figures are very sculptural in form with their draped garments suggesting the hidden shape and movement of their bodies beneath. His arrangement of the figures parallel to the picture plane is very stage like, where all the most important players are identifiable, offering the viewer a more intimate involvement in the story. In addition, he expands the flow of the narrative across the cycle of frescoes by portraying recognisable characters in different scenes. For example, we have outlined the bearded figure of Caiaphas skulking at the back of the crowd who have come to arrest Jesus, but you can see he also makes an appearance in 'Christ Driving the Buyers and Sellers out of the Temple'. Here he is seen plotting revenge with his father-in-law Annas, the High priest of the Sanhedrin, in retaliation for Jesus' driving out the merchants and money changers from the Temple and accusing them of turning God's house into "a den of thieves". Giotto’s inclusion of personal portraits, arguably the first since the Classical era, adds to the realism of the frescoes and strongly indicates that he drew his figures from life models.

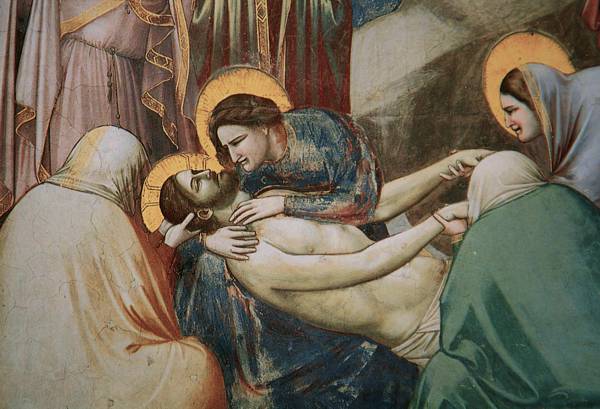

Giotto: The Scrovegni Chapel - The Lamentation over the Dead Christ (1304-06)

GIOTTO (c.1267-1337)

'The Lamentation over the Dead Christ', 1304-06 (fresco)

The 'Lamentation over the Dead Christ' is the most emotional and to many the greatest fresco panel in the Scrovegni Chapel. It is the earliest known portrayal of the dead Christ in the history of art. This is an image of human mortality with all its attendant emotions, emphasising that Jesus was both God and man. As an advocate of Franciscan spirituality, Giotto was inspired by the friars' affinity with Jesus' humanity to create a compassionate context relevant to all. This is Giotto at the peak of his creativity transforming the deepest mysteries of Christianity into accessible scenes of authentic realism that brought the scriptures to life for the common man.

All the innovative elements that Giotto had devised are used in this work to enhance the naturalism of the image. His realistic pictorial space is formed by the overlapping and layering of figures to add depth to the image. Their basic forms and evocative body language complement their expressions and eye contact to create a psychological atmosphere of heartache and distress. The inclusion of the ridge of rock in the background not only provides a setting for the figures, but also works as a compositional device that leads us to the focal point of the painting.

GIOTTO (c.1267-1337)

Detail from 'The Lamentation over the Dead Christ', 1304-06

Each component of the work is designed to draw us into the heartrending embrace between Jesus and Mary, whose grief-stricken face and gentle caress express her fluctuating emotions of loss and love. Her anguish is amplified throughout heaven by the tormented angels who wail and weep at the sorrowful scene below. A solitary sign of hope rests in the budding bush on the barren ridge of rock which symbolises Christ's forthcoming resurrection.

The only trace of Byzantine ornamentation that remains is found in the golden halos that identify Jesus’ revered companions. Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathea, both members of the Sanhedrin but secret disciples of Jesus, stand respectfully on the right, ready and waiting to support his friends and family. Saint John the Apostle throws back his arms in anguish and disbelief as he looks upon his master's dead body. The three Marys, who were first to discover Jesus' empty sepulchre after his resurrection, are among the women present. Mary Magdalen, the remorseful sinner and Jesus' principal female disciple, gently cradles his wounded feet. Mary of Cleophas, who is thought to be the sister-in-law of the Blessed Virgin, and Mary Salomé, who some authorities believe to be the Virgin Mary's sister, help to take the weight of Jesus' body as his mother caresses her dead son.

The 'Lamentation over the Dead Christ' is a deceptively simple but radical composition that allows the physical and psychological language of the figures to tell a story that speaks to all. It both starts and points to many of the future developments of painting in Western art for centuries to come.

Giotto: 'Maestà' - The Ognissanti Madonna (1310)

GIOTTO (c.1267-1337)

'Maestà' (The Ognissanti Madonna) , 1310

(tempera on wood)

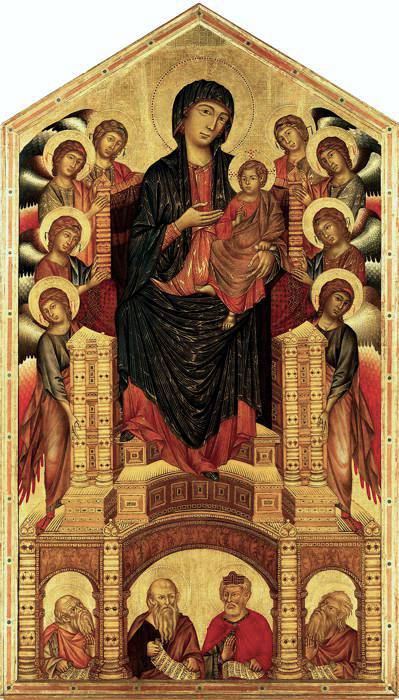

Although Giotto pursued progressive ideas in his art, he did not always dismiss the Byzantine traditions of his day. His Maestà (Majesty), later named 'The Ognissanti Madonna' after the Franciscan Church of Ognissanti (All Saints) in Florence where it first hung, is a tactful balance between the conventional guidelines for religious altarpieces and his personal artistic vision. You can clearly see the resurgence of naturalism in his work if you compare it with Cimabue's or Duccio's interpretations of the 'Maestà' which were painted between twenty and thirty years earlier.

CIMABUE (c.1240-1302)

'Maestà of Santa Trinita', 1280-90

(tempera on wood)

Cimabue's and Duccio's versions, painted respectively for the Santa Trinità and Santa Maria Novella churches in Florence, are still tethered to the Byzantine tradition. Byzantine artists did not have the freedom to express their individuality through the style of their work. The church exercised strict control over the form and content of painting to ensure there was no deviation from religious doctrine in an age where heresy and superstition challenged established theology. This was an art form where the artist had to work within tight stylistic limitations. It was a formal approach that avoided the anomalies of naturalism, generating a spiritual reverence that was inspired more by the magnificence of the artwork than any personal identification with the subject matter.

DUCCIO DI BUONINSEGNA (c.1255-1319)

'Maestà (The Rucellai Madonna)', c.1285

(tempera on wood)

Giotto’s 'Maestà' acknowledges this tradition in the frontal view of the throne and the use of expensive materials in accordance with the liturgical importance of the subject. Gold leaf is applied to represent the background of Heaven, and the pigment used to create the dark blue of the Madonna’s robe is ground from lapis lazuli, a semi-precious stone. However, it is here that the similarity ends. He adapts the structure throne with fretwork windows to view the saints standing behind it, adding three-dimensional depth to the image. He then increases its realism with a more accurate perspective, exquisite decorative details, and the illusionistic texture of its variegated marble surfaces. The figures of the Virgin Mary and Jesus are softened by their three-quarter poses, their naturalistic forms, and the Virgin's intimate eye contact, which invites the viewer to engage with the work on a more personal level. This feeling of empathy is enhanced by the adoration of the angels whose gentle bearing, soft features, and focused attention on the Child Jesus, contribute to the tenderness of the image. Giotto also adds a touch of symbolism in the gifts that the angels present: a crown for Christ the King, a eucharistic casket that represents Christ' sacrifice, and vases of roses and lilies which are generally associated with the Virgin Mary.

Although Giotto's painting may be more progressive for the time, that does not mean to say it is the better artwork. You must decide that for yourself. If anyone tells you that this or that painting is a great masterpiece, you are taking their word for it. However, the only way you will really know that for yourself is to go and see artworks in the flesh. When you view paintings in a blog or a book, they are only several inches high and their color is often inaccurate. You also lose the characteristic energy of the artist's mark-making, the vitality of the texture, and the power of its scale. If you are ever lucky enough to go to the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, you can see these three paintings together in Room 2, where the now hang. They are all around 10ft tall and when you meet them for the first time you immediately understand why they are considered masterpieces. There is no substitute for visiting galleries and venues that exhibit art and looking at real paintings, sculptures and installations.

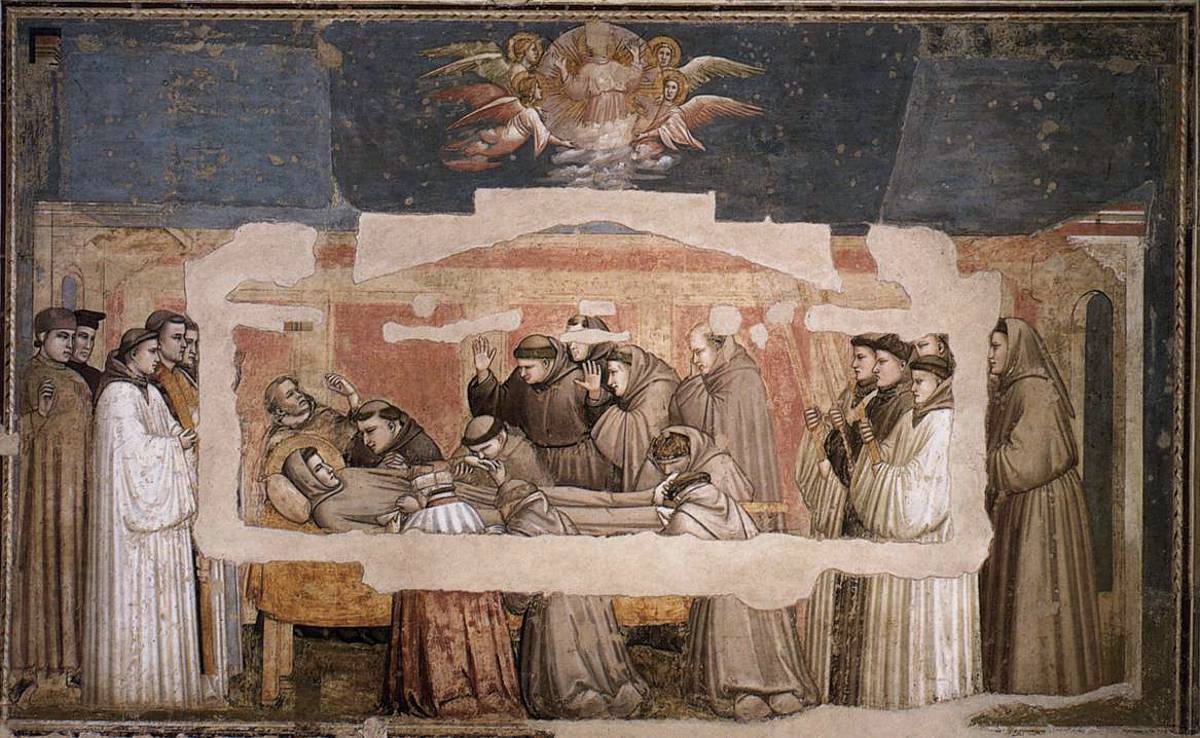

Giotto: The Bardi and Peruzzi Chapels

GIOTTO (c.1267-1337)

'The Death of Saint Francis' 1325, Bardi Chapel (fresco)

GIOTTO (c.1267-1337)

Detail of 'The Death of Saint Francis' 1325, Bardi Chapel (fresco)

Medieval and Byzantine art celebrated the celestial realm without any reference to our terrestrial world. At various times during these eras, painting a living person was considered blasphemy, as only God had the ability to create life. It was seen as an attempt to harness His power and use it for our own ends. Consequently, the conventions of most Medieval and Byzantine art avoided any depiction of the material world, focusing more on the majesty of God, the angels and saints. In contrast, Giotto’s art, which was inspired by Franciscan spirituality, links the human with the divine by portraying the humanity of Jesus as our model to follow. The Franciscan coat of arms carries the Latin maxim 'Deus Meus et Omnia' (My God and all things), emphasising that all life is sacred. This more inclusive viewpoint unites the spiritual with the physical implying that Christ is not only to be found in the kingdom of Heaven, but also in the poor, the suffering, the persecuted, the sinners as well as the saints, and the abundant lifeforms and ecosystems of this world. Through Franciscan spirituality, God's realm was expanded from Heaven to the here and now.

Giotto was the favourite artist of the Franciscans who employed him to decorate many of their churches. The Franciscans themselves, fought an internal battle over the contentious patronage of wealthy businessmen and bankers who funded these constructions, as some believed it contradicted their rule of poverty. It is a testimony to the artist's shrewd management skills that he was able to achieve his own artistic objectives in the face of the conflicting religious, economic, social and personal demands of his patrons.

GIOTTO (c.1267-1337)

The Bardi and Peruzzi Chapels in the Basilica of Santa Croce, Florence.

In the Franciscan Church of Santa Croce in Florence, Giotto was commissioned to paint four side-chapels: the Giugni Bonaparte Chapel (Stories of the Apostles), the Tosinghi-Spinelli Chapel (Stories of the Blessed Virgin), the Peruzzi Chapel (Life of St. John the Baptist and St. John the Evangelist), and the Bardi Chapel (Life of St. Francis). The artwork on the first two have all but disappeared while the Peruzzi and Bardi Chapels are the victims of persistent damp, the disaster of the River Arno flood in 1966, and extremely poor attempts at restoration. The frescoes in both these chapels were whitewashed during the eighteenth century but over-restored with insensitive enhancements and attachments in the mid-nineteenth. Between 1958-61, they were returned to their original state, albeit disfigured by their earlier restorations, the scars of which are visible in the bare patches of plaster that remain. The Peruzzi murals have suffered more as they were painted in 'fresco secco' which is a less permanent technique than the 'buon fresco' method used for the Bardi Chapel.

GIOTTO (c.1267-1337)

Left hand wall frescoes of Bardi Chapel.

Despite the poor condition of these works they give us an insight to Giotto's mature style and his influence on subsequent artists. The paintings in the Bardi Chapel follow the life of Saint Francis, a subject he had previously tackled in the Upper Church in Assisi around 25 years earlier. These images are more subdued in color as the artist has modified their contrast in the interest of unifying his composition. For example, the figures in 'The Death of Saint Francis' work as an integrated group whose expressive intensity builds from either side of the painting to reach an emotional crescendo around the head of the dead saint. The composition itself becomes the consolidating element of the work, fusing his usual devices such as eye contact and emotive body language with the form and arrangement of his figures into a powerful configuration that is greater than the sum of its parts. The idea of an optimal composition that controls the movement and rhythm of the elements in a painting in order to heighten or diminish the drama of the work, is one of the key factors of Giotto's art that appealed to forthcoming artists like Masaccio and Michelangelo and subsequently formed one of the foundation stones of Italian Renaissance art.

Giotto di Bondone Timeline

PORTRAIT OF GIOTTO (c.1490-1550)

Florentine School (tempera on panel)

Giotto is recognised as the founding father of Renaissance art. He resurrected the idea of realism in painting and revitalised a more rational approach to art based on observational drawing, a discipline that had been lost to the ritualistic design of Byzantine art following the symbolism and superstition of the Dark Ages that succeeded the decline of Classical Antiquity. His ideas, inspired by the humanity of Franciscan spirituality, paved the way to a more compassionate gospel based narrative that flourished in the hands of Renaissance masters from Masaccio to Michelangelo.

-

1265 - Giotto was born Colle di Vespignano, a small village to the north-east of Florence

-

1277-78 - Starts work as an apprentice in Cimabue's workshop.

-

1285 - Giotto made his first visit to Rome to see the great artworks of Classical Antiquity.

-

1287 - Starts work in the Basilica of Saint Francis in Assisi.

-

1290 - Giotto married Ricevuta di Lapo del Pela - a Florentine woman nicknamed "Ciuta". They had several children, one of which was named Franceso after St. Francis of Assisi.

-

1297-99 - Worked on the cycle of 28 frescoes on 'Stories from the Life of Saint Francis' in the Upper Basilica of San Francesco, Assisi.

-

1300 - Worked on a commission for Pope Boniface VII of paint a fresco in the Basilica of Saint John Lateran in Rome.

-

1303-06 - Starts work on the Scrovegni Chapel frescoes in Padua.

-

1320-25 - Paints the private chapels of the Peruzzi and Bardi families in the Basilica of Santa Croce, Florence.

-

1328 - He was summoned to work as "first court painter" to King Robert of Anjou, the ruler of Naples, where he worked in Castel Nuovo, the King's residence.

-

1334 - Returned to Florence to be made Capomaestro (Director of the Cathedral Works) where he is said to have designed the lower section of the Campanile (bell tower), one of the main buildings that comprise the Piazza del Duomo.

-

1337 - Giotto dies in Florence and was buried in the Duomo, next to his Campanile.