Surrealism

Surrealism is the 20th century art movement that explored the hidden depths of the unconscious mind.

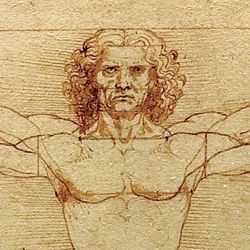

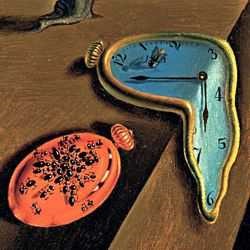

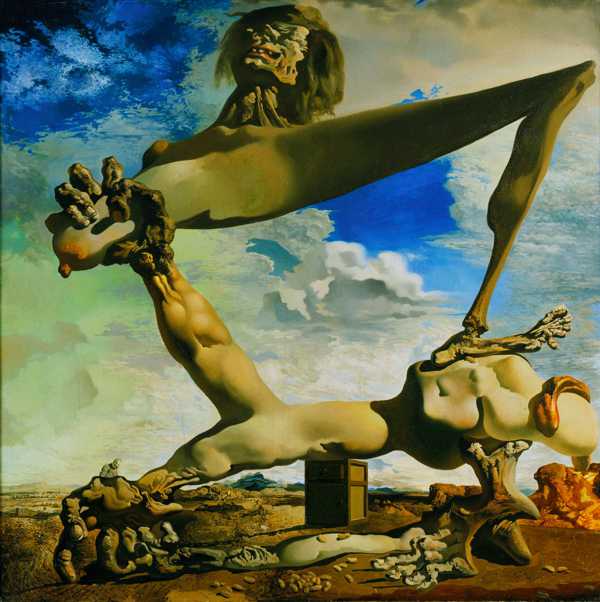

SALVADOR DALI (1904-1989)

Soft Construction with Boiled Beans (Premonition of Civil War), 1936 (Oil on Canvas)

Surrealism was the 20th century art movement that explored the hidden depths of the 'unconscious mind'. The Surrealists rejected the rational world as 'it only allows for the consideration of those facts relevant to our experience'. [1] They sought a new kind of reality, a heightened reality that they called 'surreality', which was found in the world of images drawn from their dreams and imagination.

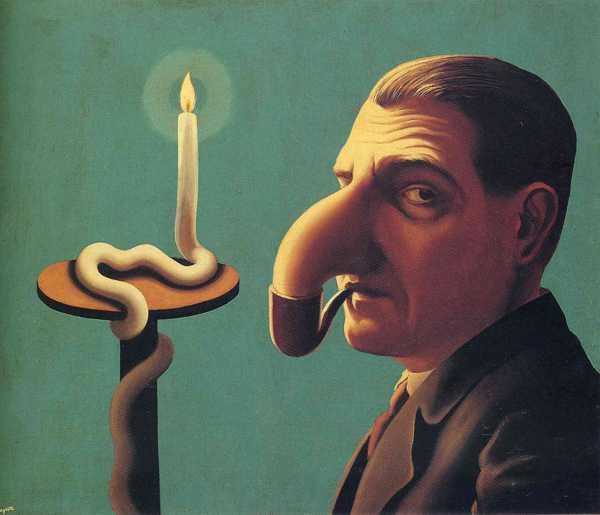

RENÉ MAGRITTE (1898-1967)

The Philosopher's Lamp, 1936 (Oil on Canvas)

Surrealism was founded in Paris where many of the Dadaists had settled after the Great War. It was originally a literary movement but its unusual imagery was more suited to the visual arts and to those artists who were searching for a more consistent approach to art as an antidote to the chaos of Dada.

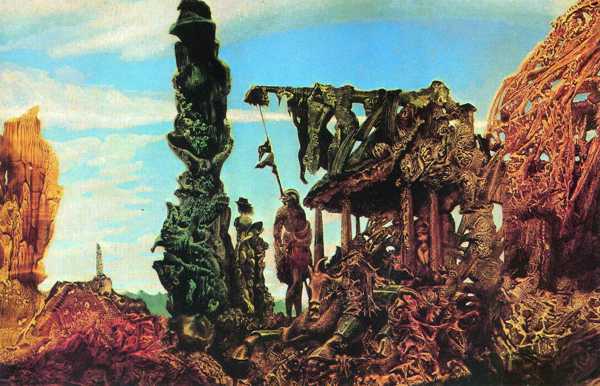

MAX ERNST (1891-1976)

The Eye of Silence, 1943-44 (oil on canvas)

Surrealism was similar in character to Dadaism as both were hostile to the traditions of academic art and the values that it stood for. The main difference between the two movements was in their method of opposition. While the Dadaists were content to blast the establishment with a scattergun of negativity, the Surrealists were in search of a more positive philosophy.

Surrealist Artists

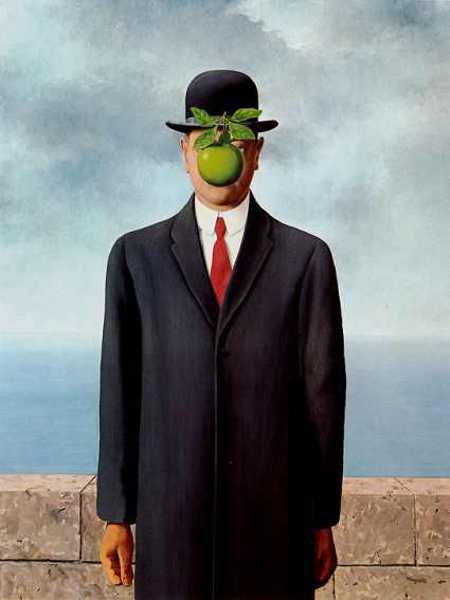

RENÉ MAGRITTE (1898-1967)

The Son of Man, 1964 (Oil on Canvas)

Over the years there have been many artists associated with Surrealism which continues to exert its influence on art to this day. However, those major figures who were responsible for creating the golden age of Surrealism were Joan Miro, Max Ernst, Salvador Dali and René Magritte.

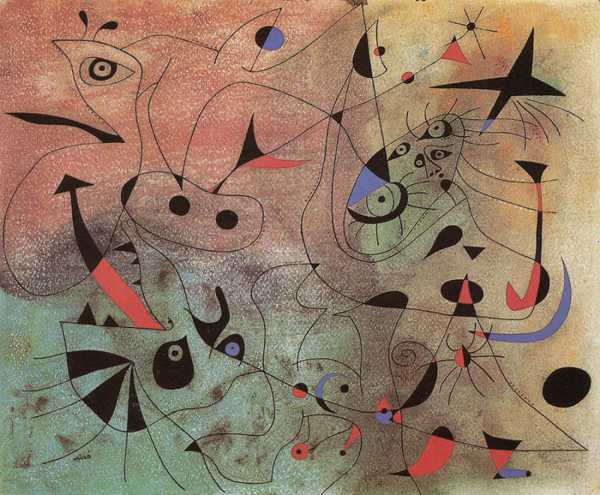

JOAN MIRO(1893-1983)

The Birth of the World, 1925 (Oil on Canvas)

Joan Miro moved from Barcelona to Paris in 1919 where he was introduced to André Breton and the Surrealists by his next door neighbour, André Masson. Breton loved the naive and childlike vision of Miro's art and encouraged him to experiment with Surrealist techniques in order to stimulate his creativity and open his 'unconscious mind'. To this end Miro tried to enhance his imagination by inducing hallucinations through extreme hunger. In this susceptible condition he would sit for hours and stare at the stains and cracks on the plaster walls of his run down studio, sketching the primal forms that were generated by his altered state. This technique was probably inspired by a favourite Surrealist text on the interpretation of stains from the notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci, "I say that a man may seek out in such a stain heads of men, various animals, battles, rocks, seas, clouds, woods and other similar things. It is like the sound of bells which can mean whatever you want it to" [2]

Miro's painting, 'The Birth of the World' perfectly illustrates this form of 'automatism'. He began the work by brushing and splashing the freely painted background, which in itself is an example of 'pure psychic automatism'. [3] However the foreground of the painting is more calculated with flatly painted lines and shapes that are drawn from a vocabulary of primal forms compiled in his sketchbooks. These forms, in relation to the title of the painting, both invite and resist literal analysis provoking an 'unconscious' poetic response as the enduring effect. As Miro said, "The painting rises from the brushstrokes as a poem rises from the words. The meaning comes later."

MAX ERNST (1891-1976)

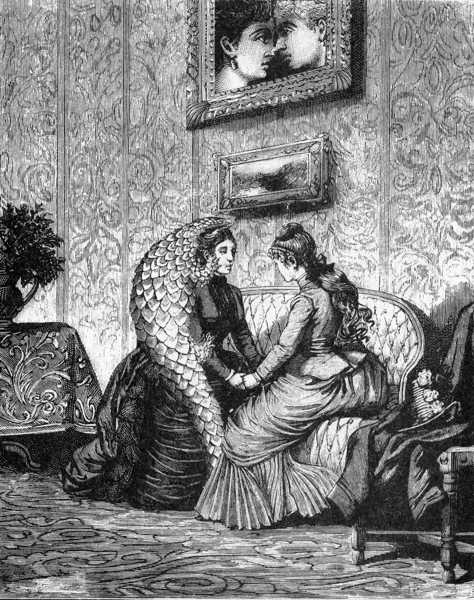

Une Semaine de Bonté, 1933 (engraving based on collage)

Max Ernst explored a wider variety of Surrealist techniques than any other artist. As Surrealism was originally formed as a literary movement, one of the problems for artists was to find Surrealist processes that were specific to the visual arts and not simply adaptations of literary techniques.

Collage and photomontage had already been used to dramatic effect by Ernst when he was a member of the Cologne Dadaists. In the context of Surrealism it proved to be the perfect medium to awaken what Ernst called 'the most powerful poetic detonations'. [4] Consequently he produced a series of Surrealist collage novels including 'Répétitions' 1922, 'Les Malheurs des Immortels' 1922, 'La Femme 100 Têtes' (One Hundred Headless Women) 1929 and 'Une Semaine de Bonté' (A Week of Plenty) 1933, a page from which is illustrated.

The images in these novels were cut and pasted from an assortment of popular scientific and literary publications. Cuttings from the likes of Gustave Doré's illustrations of 'Paradise Lost' and Jules Mary's bourgeois melodrama 'Les Damnées de Paris' were combined in bizarre and irrational relationships. Ernst's choice of sources, however, were not simply random. They represented the repressive Victorian/Edwardian era of his childhood and his collage books were a provocative assault on its authoritarian society. To enhance the subversive power of his imagery, Ernst had each collage recreated as a line engraving to make them look more like authentic illustrations of the time. As you turned the pages, the juxtaposition of images from different contexts stunned your normal cultural response and stirred the depths of your 'unconscious mind'.

MAX ERNST (1891-1976)

Detail of Europe after the Rain II, 1941 (Decalcomania: Oil on Canvas)

Ernst also developed the techniques of 'frottage', 'grattage' and 'decalcomania' to create 'automatic' textures. He would use these as an imaginative source of imagery by staring at them to discover the extraordinary surrealistic creatures and landscapes that lay hidden within.

Frottage (from the French, 'frotter' meaning 'to rub') was the technique of taking a rubbing from a textured surface, like the childhood pastime of creating an image of a coin by covering it with a sheet of paper and rubbing with a pencil.

Grattage (from the French, 'gratter' meaning 'to scratch') was another 'automatic' technique that explored the after-effects of scraping wet paint from the surface of a canvas.

Decalcomania was one of Ernst's more dynamic techniques. This effect is clearly illustrated in his painting of 'Europe after the Rain II'. Its elaborate surface was created by pressing fluid paint between two sheets of canvas and peeling them apart to reveal a luxuriant texture. Ernst would then search this complicated mass for familiar shapes much in the same way that a psychologist would use the 'Rorschach inkblot test' to extract meaning from an 'automatic' response. Once he had unearthed some recognizable figures that formed a subliminal narrative, he would enhance their details manually. Finally he would edit the overall composition by painting out the negative shape of sky to liberate the 'unconscious' image that was hidden within its entangled form.

'Europe after the Rain II' is Max Ernst's scathing commentary on World War Two in Europe. It is an apocalyptic vision of the aftermath of war; a scorched world of rotting remains that are inhabited by the deformed shapes of man and beast. A woman with her back to us stares longingly at the distant horizon grieving for her lost world, her calcified body eternally anchored to this barbarous terrain. A sentry wearing a bird mask helmet and holding a spear stands guard beside her, an ironic symbol of the 'great European New Order' that Hitler proclaimed in a speech of January 1941 (the year of the painting) at the Berlin Sportpalast.

Ernst experienced the devastation and futility of war having served on both the Western and Eastern fronts in World War One. In his autobiography he dealt succinctly with these harrowing events, 'On the first of August 1914, M E died. He was resurrected on the eleventh of November 1918'. [5]

'Europe after the Rain II' is an 'unconscious' visualization of all wars: no idealistic outcome, no victor's spoils, no winners. All that remains is a ravaged world and a scarred humanity whose new guardian now wears a different mask. When interviewed about the relationship between dreams and reality in his work and the strangeness of the images he produced, Ernst replied "If painting is a mirror of a time, it must be mad to have a true image of what the time is. Who made world history? Not the most reasonable people, the madmen did......Through one madness we oppose another madness." [6]

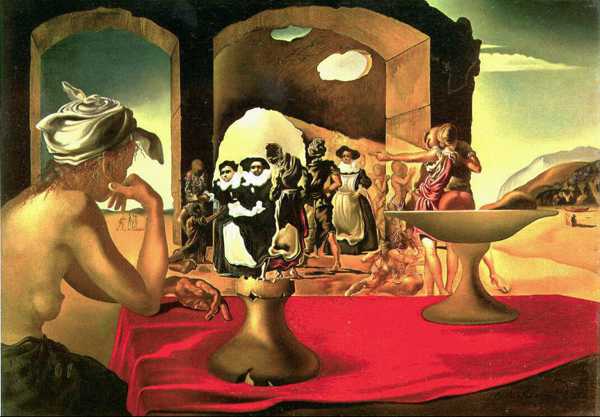

SALVADOR DALI (1904-1989)

Swans Reflecting Elephants, 1937 (Oil on Canvas)

Salvador Dali personifies Surrealism. He was fascinated by the writings of Freud and his interest in psychoanalysis informed his best work. He proudly proclaimed "There is only one difference between a madman and me. I am not mad....There is more to the nightmarish world than people think." [7]

Dali was enthralled by certain delusional aspects of paranoia: how a person sees evidence of one thing and irrationally interprets it as another. By entering a self induced paranoiac state he was able to contemplate one form and conceive it as another - a kind of illusionistic double-take. True to Surrealist form, Dali adopts a mental disorder and turns it into an mechanism for mining the 'unconscious mind'. He called this his 'paranoiac-critical' method and he used it repeatedly in his classic surrealist paintings of the 1930's. Dali's works of this period were also very accessible to the wider public due to the virtuosity of his painting technique. He was able to create very believable images whose lifelike description convinces us that this unconscious world of his dreams is real.

SALVADOR DALI (1904-1989)

Metamorphosis of Narcissus, 1937 (Oil on Canvas)

The 'Metamorphosis of Narcissus' was the first painting that Dali based on his 'paranoiac-critical' method. It was inspired by the various myths of Narcissus which explore an abnormal preoccupation with the self, something that Dali was no stranger to.

In Greek mythology the young Narcissus was renowned for his handsome looks but he was also infatuated by his own appearance. One day he met the beautiful nymph Echo while hunting in the woods. Echo, who was a bit of a chatterbox, had fallen in love with Narcissus but as the result of a curse, she was only able to repeat those words that had previously been spoken to her by another. So when Narcissus spoke to her she could only repeat what he said. In a confused and frustrated state he spurned her advances and ran away. Echo, heartbroken by his rejection, retreated to the wilderness where she pined away until only her voice remained. In the meantime Narcissus continued to reject suitor after suitor until Nemesis, the goddess of vengeance decided to punish him for his egotism. She lured him to an enchanted pool to quench his thirst and as he knelt down to drink, he fell in love with his own reflection in the water. He became so spellbound by the allure of his own image that he was unable to move. Transfixed and brokenhearted, just like the lovesick Echo, he gradually wasted away to nothing and died. At the place where he knelt a flower grew which was named after him.

Dali's tells his story of Narcissus in two forms, one an echo of the other. The form on the left is the figure of Narcissus as he bends to look at his reflection in the pool. His body is turning to stone which both illustrates his inability to move and indicates his eventual death. The form on the right is his dead, petrified body which has transformed into a hand holding an egg. A narcissus grows from a crack in the egg to complete his metamorphosis.

Dali crafts the rest of the painting around this 'paranoiac critical' vision. The composition of the painting is cut in half by the vertical edge of the cliff face on the left. This draws a dividing line between the two forms of Narcissus and the symbolic balance of their color. The warm colors of the Cap de Creus rocks are used on the left, in and around the dying Narcissus, to suggest that there is yet life in his ailing body. (The Cap de Creus is a headland near Figueres, Dali's birthplace, and its typical rock formations appear in many of his works.) The colors on the right have turned ice cold to convey the idea that Narcissus has passed on. His metamorphosed form stands like a tombstone overrun by ants, his spirit encapsulated by the surviving flower. Ants, which also appear in several other paintings by Dali, are used as symbols of transformation as they constantly collect and consume dead matter to recycle its energy.

In the center of the painting, a winding road links both images of Narcissus as it heads off into the distant mountains. Where it passes between the two forms, a group of Narcissus' rejected suitors weep in grief for their loss. A sense of loss is further developed in the figure on the right who stands on a plinth in the center of a checkerboard. This represents Narcissus as he formerly was, glancing round to admire his own physique.

The dramatic lighting, intense color, distant perspective and theatrical arrangement of the composition all nod a debt of acknowledgement in the direction of De Chirico, but what lifts Dali's 'hand painted dream photographs' [8] to a higher order in the Surrealist hierarchy is the ability of his painting technique 'to materialize the images of my concrete irrationality with the most imperialist fury of precision'. [9]

RENÉ MAGRITTE (1898-1967)

The Human Condition, 1933 (Oil on Canvas)

René Magritte's paintings explore the 'unconscious' gaps between the communication and interpretation of the words and images that we use to describe reality. He paints commonplace images that set a trap for our rational faculties with their visual and verbal tripwires. The interplay between the titles and the content of his paintings adds another level of disorientation to these philosophical conundrums.

'The Human Condition' (1933) portrays a canvas on an easel in front of a window. The image on the canvas is a landscape painting which exactly registers with the view through the window. This immediately makes us pause and think, 'How do we know that the landscape behind the painting is what we see on the canvas? Is the image on the canvas revealing or concealing a view of reality?' The answer is that we simply don't know because we cannot move the painting to find out. Therefore, the reality of what exists is either accepted as an act of faith or becomes a construct of the mind, both philosophical perspectives of the human condition.

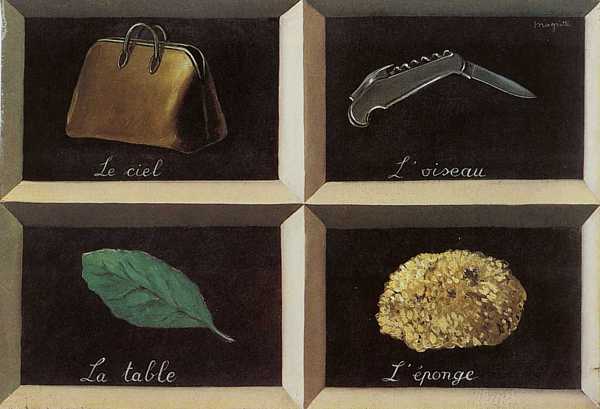

RENÉ MAGRITTE (1898-1967)

La Clef des Songes (The Key to Dreams), 1927 (Oil on Canvas)

Magritte constructs a similar enigma in 'La Clef des Songes' where he creates a gap between the meaning of words and images. The painting looks like a child's picture dictionary and is painted in that bland functional manner. It depicts four objects - a bag, a penknife, a leaf and a sponge, each with an identification label below - Le ciel (The sky), L'oiseau (The bird), La table (The table) and L'éponge (The sponge). This simple image-labelling format is one that we have all learned to recognise and trust since childhood. However, here it does not work in three out of the four examples. The strange thing is that we do not automatically accept that the labelling system is wrong. As one of them is correct we start to search for a new system that works, exploring new possibilities for shape, color and form to try to restore a rational sense of order. It is at this point that Magritte has us where he wants us: absorbed in Surrealist activity by stimulating the creative potential of our unconscious mind through engaging with the impossible.

YVES TANGUY (1900-1955)

Deux Fois du Noir, 1941 (Oil on Canvas)

There is long list of Surrealist techniques that were devised to tap into the 'unconscious mind' and most of the artists explored a range of these in their work. However, the essence of Surrealist art can be summarized in three basic techniques:

- Automatism

- The Interpretation of Dreams

- The Juxtaposition of Unrelated Images

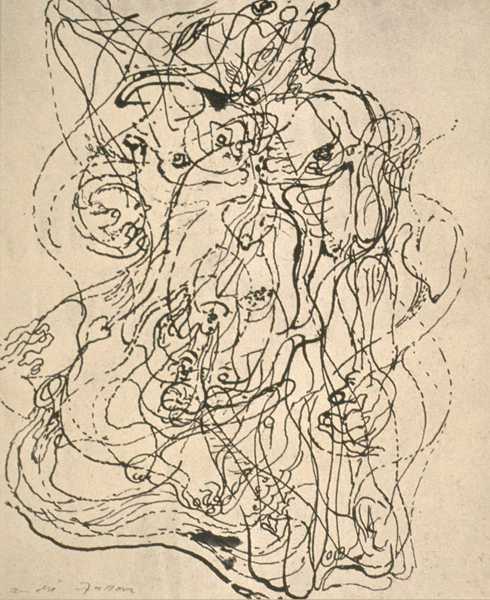

ANDRÉ MASSON (1896-1987)

Automatic Drawing, 1924 (Pen on Paper)

Automatism is based on a technique of Sigmund Freud called 'free association'. He wrote that, 'The importance of free association is that the patients spoke for themselves, rather than repeating the ideas of the analyst; they work through their own material, rather than parroting another's suggestions''. [10] André Breton adapted this therapy as a creative device, renaming it 'pure psychic automatism'. [11] In this technique the artist would empty their mind of conscious thought and then start to draw spontaneously, recording any response that filled the vacuum. The result would be an expression of the 'unconscious mind' revealing the hidden depths of the psyche. Usually the results of this technique were not seen as the finished product but as a foundation on which a more considered image could be crafted, thereby achieving the 'resolution of these two states, dream and reality'. [12] This process came to be known simply as 'Automatism' and was a key element of Surrealist technique.

JOAN MIRO (1893-1983)

Constellation: The Morning Star, 1940 (Gouache and Turpentine Paint on Paper)

Automatism was the first Surrealist technique to be developed and the artworks created through this method are mostly abstract in form but often link to reality through their titles. Automatism was pioneered by André Masson, creatively developed by Max Ernst and elegantly refined in the art of Yves Tanguy and Joan Miro.

The Interpretation of Dreams

SALVADOR DALI (1904-1989)

Slave Market with the Disappearing Bust of Voltaire, 1940 (Oil on Canvas)

As a student of psychiatry, Breton was fascinated by Sigmund Freud's study on 'The Interpretation of Dreams'. In his book of 1899 Freud stated that our deepest memories and instincts were hidden in the 'unconscious mind' and that one method of unlocking these was through the analysis of our dreams. Freud's ideas on the psychology of dreams, albeit adapted to suit Breton's own needs, were to become central to the development of Surrealism.

RENÉ MAGRITTE (1898-1967)

The Return, 1940 (Oil on Canvas)

The master of the hallucinatory dreamscape was Salvador Dali. His illusionistic realism was designed to subvert your senses and open your mind to the irrational. René Magritte also undermined the meaning of the commonplace image with an illogical visual or verbal twist that sabotaged any rational understanding of its context.

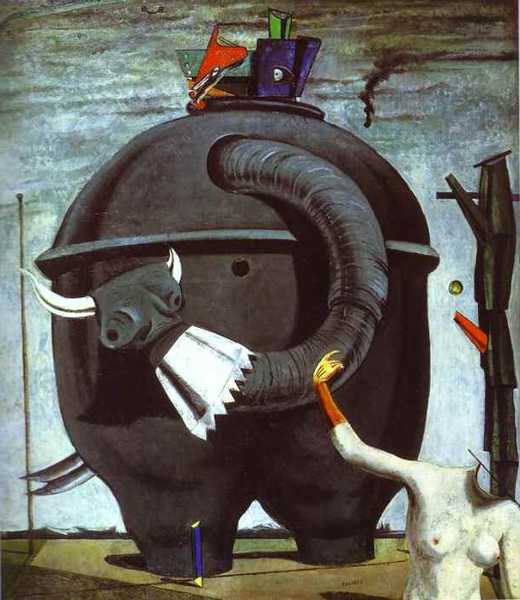

MAX ERNST (1891-1976)

The Elephant Celebes, 1921 (Oil on canvas)

Using the juxtaposition of unrelated images to generate a subconscious response was a device that Max Ernst had previously explored in his Dadaist paintings and collages. However Breton attributes the idea to the French poet Pierre Reverdy who wrote, 'The more the relationship between the two juxtaposed realities is distant and true, the stronger the image will be -- the greater its emotional power and poetic reality.' [13]

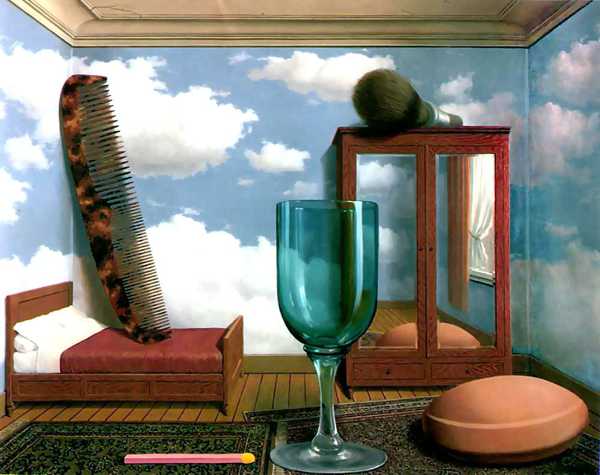

RENÉ MAGRITTE (1898-1967)

Personal Values, 1952 (Oil on Canvas)

This technique was comprehensively explored in the art of Max Ernst and imaginatively reinvented time and again in the poetic visions of René Magritte.

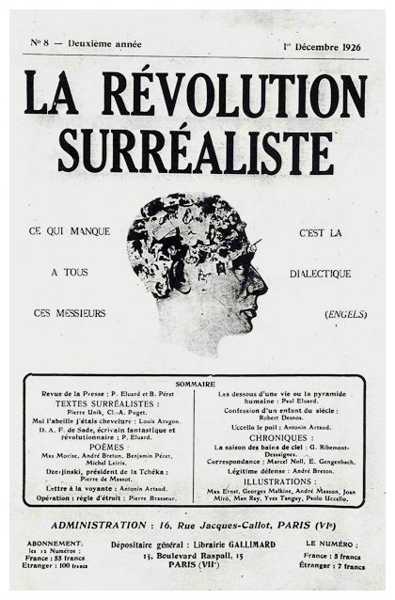

Cover of La Révolution Surréaliste (December 1926)

André Breton was a French writer and poet who wrote the first and second Surrealist Manifestos (1924 and 1929), Surrealism and Painting (1928) and was editor of the magazine La Révolution Surréaliste (twelve issues between 1924-29).

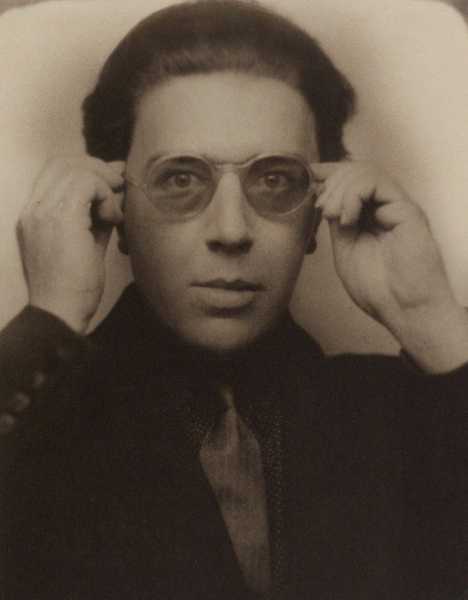

André Breton (1896-1966)

Surrealism was first defined by André Breton in the Surrealist Manifesto of 1924. He presented this definition in a format that we associate with entries in a dictionary and encyclopedia:

'Surrealism, noun. masc., Pure psychic automatism, by which it is intended to express either verbally or in writing, the true function of thought. Thought dictated in the absence of all control exerted by reason and outside all aesthetic or moral preoccupations.

Encycl. Philos. Surrealism is based on the belief in the superior reality of certain forms of associations previously neglected, in the omnipotence of the dream, and in the disinterested play of thought. It leads to the permanent destruction of all other psychic mechanisms and to its substitution for them in the solution of the principal problems of life.' [14]

In the same manifesto, Breton outlined his main aim as 'the future resolution of these two states, dream and reality, which are seemingly so contradictory, into a kind of absolute reality, a surreality, if one may so speak.' [15] He believed that this new state would transform creative thought and liberate society to live on a higher plane of 'super-reality'.

ANDRÉ MASSON (1896-1987)

In the Tower of Sleep, 1938 (Oil on Canvas)

Surrealism was first defined by André Breton in the Surrealist Manifesto of 1924.

-

Surrealism was greatly influenced by the writings of Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis.

-

Surrealism was the 20th century art movement that sought to liberate creativity from the limitations of rational thought.

-

Surrealism explored the hidden depths of the 'unconscious mind'.

-

The Surrealists saw their historical ancestors in artists like Hieronymus Bosch, Giuseppe Archimboldo, Goya, Henry Fuseli, Gustave Moreau, Odilon Redon and genres such as Folk, Primitive, Ethnic and what we now call 'Outsider Art'.

-

The most immediate influence of Surrealism was the Italian artist, Giorgio de Chirico who developed a style of painting called 'Pittura Metafisica' (Metaphysical Art).

-

Automatism was the first Surrealist technique to be developed and the artworks created through this method are mostly abstract in form.

-

Automatism was pioneered by André Masson and developed by Max Ernst and Joan Miro.

-

The interpretation of dreams was a source of inspiration for many Surrealist artists.

-

Salvador Dali was the master of hallucinatory dreamscapes.

-

Dali's illusionistic realism could subvert your senses and open your mind to the irrational.

-

The juxtaposition of disassociated images was a technique that Max Ernst and René Magritte employed to generate a Surrealist reaction in the mind of the spectator.

-

The main artists associated with what we now call the 'Golden Age' of Surrealism comprise André Masson, Max Ernst, Joan Miro, Salvador Dali and René Magritte.