Aboriginal Dot Painting

Aboriginal Dot Paintings are what most people think of as modern indigenous Australian art. This unique style of painting which has gained a global reputation since it emerged in 1971, grew out of an encounter between an art teacher and a community of displaced Aboriginal people in Papunya.

'Turtle Dreaming'

© www.artyfactory.com

Aboriginal Dot Paintings are what most people think of as modern indigenous Australian art. This unique style of painting which has gained a global reputation since it emerged in 1971, grew out of an encounter between an art teacher and a community of displaced Aboriginal people in Papunya.

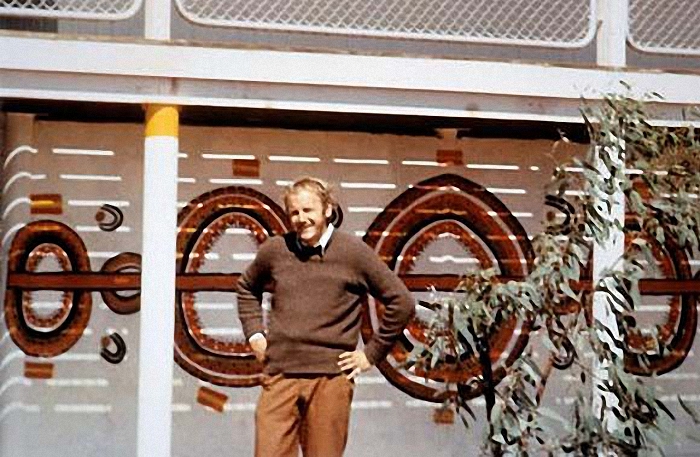

Geoffrey Bardon with the 'Honey Ant Dreaming' Mural at the Papunya School.

In 1971, Geoffrey Bardon, a graduate from the National Art School in Sydney, took up a post as a primary school teacher in the remote government settlement at Papunya, about 150 miles northwest of Alice Springs in the Northern Territory. In order to gain the trust of the various indigenous groups, Bardon integrated socially with the community and immersed himself in their language and culture. As an artist he was intrigued by the 'dot and circle' designs he saw in Aboriginal body painting and sand drawings. In his desire to record the ephemeral nature of this art, which was either washed, trampled or blown away after the event, Barton encouraged his students to commit these symbols to the more permanent medium of synthetic polymer paints (acrylics).

When he proposed the idea for a Papunya School mural featuring a traditional design, he discovered that his students could not participate, as only the older men in the community had the authorisation to paint their ancestral designs. After much discussion among the tribal elders, Old Tom Onion Tjapangati gave permission for his 'Honey Ant Dreaming' story to be used as the subject of the mural and Kaapa Tjampitjinpa, a former stockman, was put in charge of the project, assisted by Long Jack Tjakamarra and Billy Stockman Tjapaltjarri.

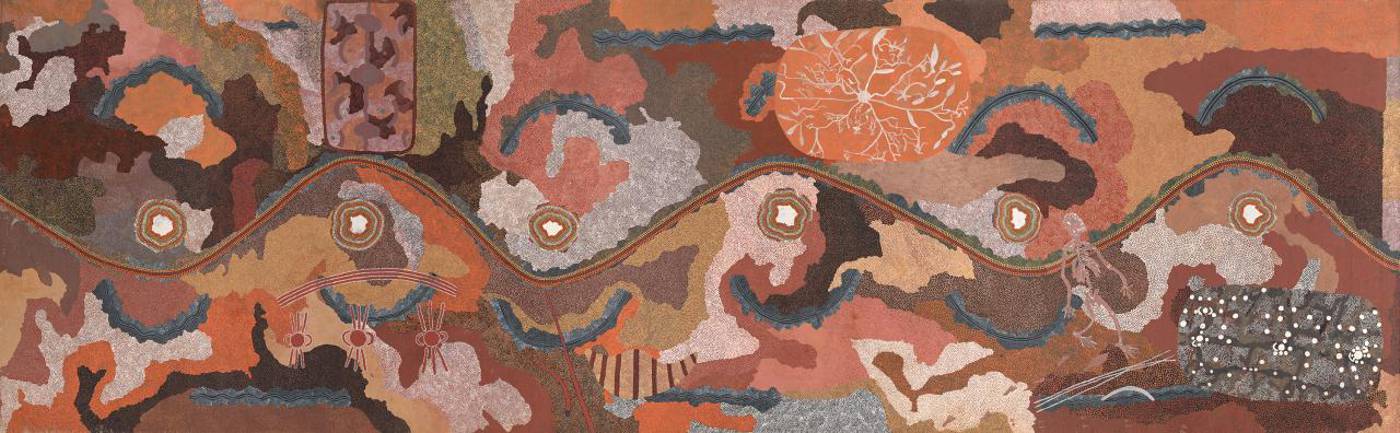

CLIFFORD POSSUM TJAPALTJARRI (1932-2002)

'Mount Wedge' 1985 (synthetic polymer paint on linen)

© Estate of Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri

When the finished mural was a such a success, attracting unforeseen interest from across the country, Bardon arranged an area at the back of his art room so that the men could continue to paint. Former Aboriginal hunters, healers, cooks, stockmen, yardmen and labourers all attended his class and were supplied with polymer paints and boards to develop their creative skills. Not only was the work personally rewarding, but after their humiliation in the wake of the government's 'assimilation' policies, painting the traditional stories from the land of their ancestors helped to restore their sense of cultural identity.

As their catalogue of paintings grew and the demand for their work increased, individuals such as Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri began to emerge as significant artists. In 1972, Bardon organized The Papunya Tula Artists PTY. LTD, a cooperative to promote their work and protect their rights. Kaapa Tjampitjimpa, the artist who took charge of the Papunya mural was appointed as the first chairman of the group which is still in existence today, representing both male and female Aboriginal artists throughout Western Australia

The Origins of Dots in Aboriginal Art

Detail of Ancient Aboriginal carving technique on rock.

The 'dot and circle' imagery that characterises the paintings of the Papunya artists has its roots in Aboriginal rock art, sand drawing (images traced in the sand to accompany story telling) and body painting.

In the ancient rock carvings, artists would bore holes to map out the direction of a line drawing instead of carving an uninterrupted outline directly into the rock. Only when the required shape was completed, would they carve the line by joining up the dots. Over the centuries, many of the line carvings in the rocks have been eroded by the elements leaving the deeper pattern of holes more visible. In the magnified section of our photograph above you can see the punctuated line of the kangaroo carving, a practical technique that suggests the dotted outlines of subsequent Aboriginal art.

Dot and Circle Patterns in Aboriginal Body Art.

Aboriginal Body painting is another indigenous art form that uses 'dot and circle' designs. The man in the photograph above is checking the progress of his body art in a mirror, while the man behind him, possibly the artist, awaits his reaction. The designs, which are always painted by another tribesman, are traditional patterns that vary between the different Aboriginal groups across the country. They are applied for religious ceremonies and display the family group, status and tribal ancestry of the person who bears them. Their pigments are mixed with animal fat to create a greasepaint that lasts throughout the ceremony, which can be up to several days long.

The Development of Dot Painting in Papunya

Kaapa Tjampitjimpa (1926-89)

'Wild Potato' 1974-75 (synthetic polymer paint on board)

© Estate of Kaapa Tjampitjinpa

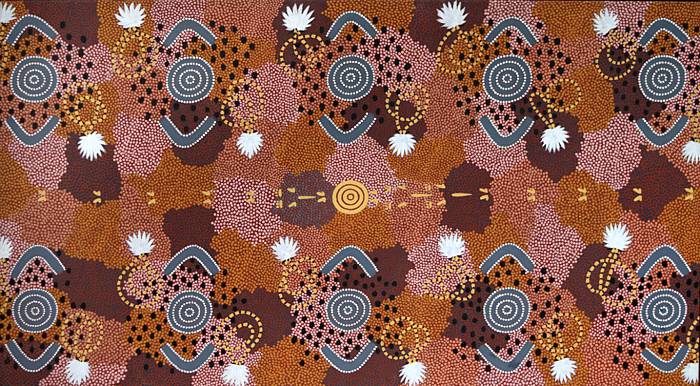

When the Papunya Tula artists first started painting at the back of Geoffrey Bardon's classroom, their main source of inspiration was the dotted designs derived from their body art and sand drawings. Transferring this iconography into polymer paint on board and canvas was a natural artistic progression. Although their imagery appeared abstract to an uninformed Western eye, they were painting the same subjects that any artist from any continent from any era would paint: their Gods, their myths, their customs, their history, their relationship with the natural world and the land that supported them.

Synthetic polymer paint was the ideal medium for the Papunya artists. It came in a wide spectrum of colors that were easy to apply in both flat and dotted areas; it dried quickly to form a waterproof film which was important for working outdoors; and its flexible surface did not crack when a canvas was rolled up for transportation.

There was, however, one major issue that arose from the use of this new medium. When a sacred story was painted on a body or drawn in the sand of their tribal lands, it was only visible to the initiated and could be wiped off or swept away to protect its secrecy. The permanence of acrylic paints meant that sacred and secret knowledge could be retained for public display and would therefore be visible to the uninitiated. This was completely at odds with Aboriginal law.

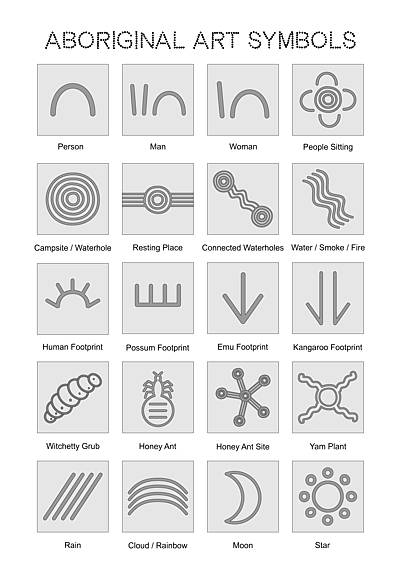

One solution to the problem was to abandon the use of secret symbols and images altogether and work with a vocabulary of conventional symbols that were accessible to all and suitable for public display.

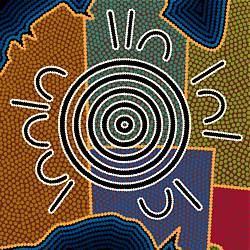

CLIFFORD POSSUM TJAPALTJARRI (1932-2002)

'Sun Tjukurrpa' 1972 (synthetic polymer paint on board)

© Estate of Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri

Another more creative solution, and one that would change the future of Aboriginal art, was to mask any secret information with patterns of dots, an extension of the traditional technique used to outline the elements of a design. A fortuitous by-product of this was the powerful graphic effect generated by the field of pulsating dots. Artists then harnessed this effect to represent different types of terrain (the Land) or express the mystical energy of a spiritual force (the Dreaming), two of the key elements of Aboriginal art.

The visual language of dots permeates most Papunya paintings and the variety of dotting techniques is considerable. Some artists are meticulous and organized in the way they apply dots; others are bold and expressive; some use dots spaced evenly apart; others merge their dots into fields of color; some use dots to outline a shape; others use them to form a shape; some use small dots; some use large dots; some use flat dots; some use raised dots; some use neat dots; some use smudged dots; and some use dots within dots.

CLIFFORD POSSUM TJAPALTJARRI (1932-2002) and TIM LEURA TJAPALTJARRI (1929-84)

'Spirit Dreaming through Napperby Country' 1980 (synthetic polymer paint on canvas)

© Estates of Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri and Tim Leura Tjapaltjarri

Within a few decades, dot painting has come to characterise indigenous Australian art, changing the perception of a culture that had been overlooked by the art world. Starting with the simple introduction of synthetic polymer paints as a new medium for traditional art, the humble model that Geoffrey Bardon established at Papunya has grown through a range of styles, techniques and imagery to become the prototype for Aboriginal art movements across the country, and the first Australian Art movement to register on an international scale.

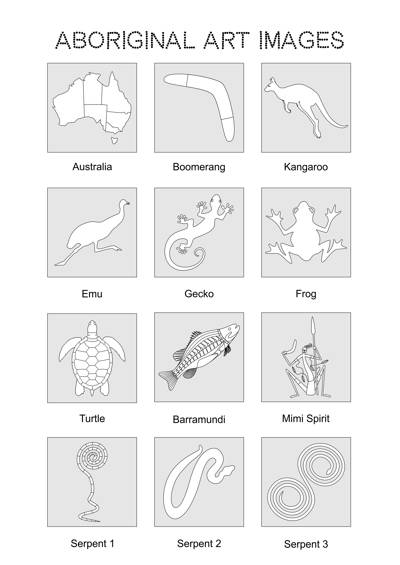

The Painting Process for our Page Illustration

Many of the topics in our Aboriginal Art pages are illustrated with a painting that was inspired by the theme of that page. For each of these we have created a step by step slide show that deconstructs the image to reveal the painting process and inspire possibilities for your own ideas. The images and symbols used to create our illustrations can be found in our menu at the foot of the page. They are available for you to download to help with creating your own artworks.

- aboriginal-dot-art

Aboriginal Dot Art

- aboriginal-dot-art-2

1. The outline of a turtle is drawn with a white color pencil on a black ground.

- aboriginal-dot-art-3

2. The turtle is repeated, rotating its angle in a clockwise direction.

- aboriginal-dot-art-4

3. A third turtle is drawn to complete a balanced rotational movement.

- aboriginal-dot-art-5

4. The surrounding space is filled with undulating shapes to suggest reflections in the water.

- aboriginal-dot-art-6

5. Blue variegated dots are painted between the shapes to suggest the watery depths.

- aboriginal-dot-art-7

6. Concentric spirals of dots are applied to echo the swirling motion of the water.

- aboriginal-dot-art-8

7. The undulating reflections are painted with a flat blue.

- aboriginal-dot-art-9

8. The turtles are painted with their natural colors.

- aboriginal-dot-art-10

9. The undulating reflections are outlined with bright aquamarine dots.

- aboriginal-dot-art-11

10. The pattern of the turtle shells is strengthened with an outline of black dots.

- aboriginal-dot-art-12

11. Sections of the turtles are outlined with bright green dots to increase their vitality.

- aboriginal-dot-art

12. The turtles are finally highlighted with vibrant orange dots linking them to the motion of the water.

(Click on the play buttons or swipe back and forward to explore each stage of our painting.)

Key Stages of the Painting

-

The outline of a turtle is drawn with a white color pencil on a black ground.

-

The turtle is repeated, rotating its angle in a clockwise direction.

-

A third turtle is drawn to complete a balanced rotational movement.

-

The surrounding space is filled with undulating shapes to suggest reflections in the water.

-

Blue variegated dots are painted between the shapes to suggest the watery depths.

-

Concentric spirals of dots are applied to echo the swirling motion of the water.

-

The undulating reflections are painted with flat blue.

-

The turtles are painted with their natural colors.

-

The undulating reflections are outlined with bright aquamarine dots.

-

The pattern of the turtle shells is strengthened with an outline of black dots.

-

Sections of the turtles are outlined with bright green dots to increase their vitality.

-

The turtles are finally highlighted with vibrant orange dots linking them to the motion of the water.