The Visual Elements - Texture

Texture in art is the surface quality of an artwork - the roughness or smoothness of the material from which it is made.

JAN VAN HUYSUM (1682-1747)

Detail of Bouquet of Flowers in an Urn, 1724 (oil on canvas)

The Visual Element of Texture defines the surface quality of an artwork - the roughness or smoothness of the material from which it is made. We experience texture in two ways: optically (through sight) and physically (through touch).

Optical Texture: An artist may use his/her skilful painting technique to create the illusion of texture. For example, in the detail from a traditional Dutch still life above you can see remarkable verisimilitude (the appearance of being real) in the painted insects and drops of moisture on the silky surface of the flower petals.

Physical Texture: An artist may paint with expressive brushstrokes whose texture conveys the physical and emotional energy of both the artist and his/her subject. They may also use the natural texture of their materials to suggest their own unique qualities such as the grain of wood, the grittiness of sand, the flaking of rust, the coarseness of cloth and the smear of paint.

Ephemeral Texture: This is a third category of textures whose fleeting forms are subject to change like clouds, smoke, flames, bubbles and liquids.

Our selection of artworks illustrated below have been chosen because they all use texture in an inspirational manner. We have analyzed each of these to demonstrate how great artists use this visual element as a creative force in their work.

Optical Texture

JAN VAN HUYSUM (1682-1747)

Bouquet of Flowers in an Urn, 1724 (oil on canvas)

Jan Van Huysum was one of the most influential Dutch still life artists of the 18th century. Dutch artists developed still life as an independent genre to fill their employment gap when religious art was banned by the Protestant churches during the Reformation. Van Huysum was famous for his magnificent flower paintings whose compositions were a mixture of Baroque chiaroscuro and Rococo flamboyance. As a subject they perfectly satisfied the Dutch love of horticulture and met the demand for decorative artworks for the houses of the rich merchant classes who had taken over from the Catholic church as the main patrons of the arts. The advantage of owning a Van Huysum flower painting over a real bouquet of flowers, which would have been outrageously expensive at the time, was that it was permanent and not subject to decay. It was therefore seen as superior to nature.

You can see that Van Huysum's pictures were not painted as a unified arrangement from life as there are a variety of flowers in the group which bloom in different seasons. He would construct and paint these works from separate studio studies of individual stems, buds and blossoms which he would carefully adapt and compose to create his spectacularly colorful displays.

It was Van Huysum's stunning painting technique that elevated his status to that of the greatest Dutch painter of flowers. At this time, the quality of realistic representation in a picture was seen as a measure of excellence. The Dutch even had a word for it - 'bedriegertje' which means 'little deception'. His outstanding ability to paint the realistic textures of petals, stems, leaves, droplets of moisture, a horde of insects and the distinctive surfaces of terra cotta vases and marble pedestals, left his contemporaries standing still. We do not know a great deal about Van Huysum's painting methods as he was extremely secretive about his technique, to the extent where he refused to allow anyone into his studio while he was working. He once employed an apprentice, Margareta Haverman, but discharged her as he felt that her competent copies of his paintings were devaluing his own.

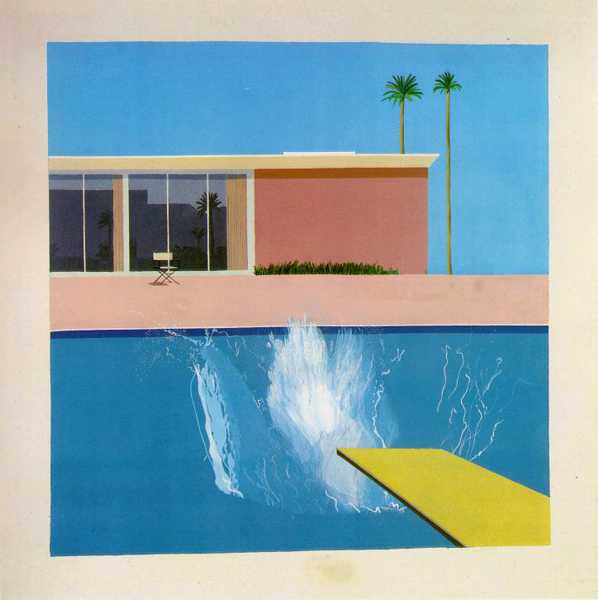

DAVID HOCKNEY(b.1937)

A Bigger Splash, 1967 (acrylic on canvas)

A Bigger Splash' is one of a series of swimming pool paintings that David Hockney used to explore various methods of representing the ephemeral texture of water. It also involved his continual interest in the relationship between painting and photographic methods of recording what we see. You can observe the development of these ideas in the way he uses photography to enable him to see what is invisible to the naked eye. The 'splash' is painted from a photographic source found in a magazine about swimming pools while the rest of the image is based on his drawings of Californian buildings. The ephemeral texture of the 'splash' only becomes visible to the naked eye when it is frozen in a photograph. Hockney originally considered creating a real splash by throwing liquid paint at the canvas but thought it would be more interesting to paint its precise shape by hand. He was amused by the irony that something which only existed for a fraction of second would take him a couple of weeks to paint. The image, therefore, becomes a commentary on the relationship between painting and photography and how each can be used to inform the other.

LUCIAN FREUD (1922-2011)

John Minton, 1952 (oil on canvas)

Lucian Freud's portrait of his friend and fellow artist, John Minton, is one of his early masterpieces. His works of this period have something of the intense character of Northern Renaissance portraits by artists like Robert Campin and Roger van der Weyden. They are painstakingly painted in fine detail with soft sable brushes to render the subtle variations of the tone and texture of the eyes, skin and hair. Freud's unrelenting focus on each and every square centimeter of Minton's head plots a map of microexpressions that reveals a state of unease in the sitter. Variegated textures combine to communicate this underlying sense of disquiet: the tussled layers of his hair, the wateriness of his eyes, the oiliness of his skin, his loose mouth and the muscularity of his lips, and all in concert with the tilt and elongation of his head. This is a meticulously observed portrait whose surface textures work together to reflect the psychological state of their subject.

DUANE HANSON (1925-1996)

Man on a Bench, 1977 (vinyl, polychromed in oil, with accessories)

Photo: Metropilot ©

Duane Hanson takes optical texture to the ultimate level of realism in his life size sculpture of a 'Man on a Bench'. He cast this dejected figure from life, heightening its accuracy with subtly painted veins shining through its translucent wrinkled skin. The addition of fastidious details like naturalistic eyes, lashes and stubbly eyebrows, thinning grey hair, socially defining and age-appropriate clothes lifts the work to an uncanny level of deception.

Due to its human scale and verisimilitude it is hard to ignore this sculpture. It has a remarkable presence which is strengthened by the placement of the work where it invades the space of the spectator demanding a response to its despondent subject - a barometer of your empathy or apathy towards your fellow man.

Hanson's work is a commentary on contemporary life from a working class perspective. Some of his subjects are brutal and violent, some tackle sensitive social issues and some simply reflect man's sense of alienation in our world today. They are a modern reincarnation of the spirit of Realism that was reawakened by the noise of Pop Art.

Physical Texture

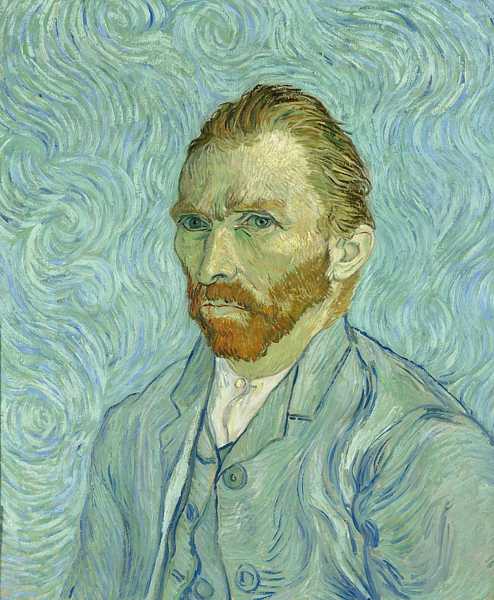

VINCENT VAN GOGH (1853-1890)

Self Portrait, 1889 (oil on canvas)

In his famous self portrait of 1889 from the Musée d'Orsay, Vincent Van Gogh uses the physical texture of paint not only to fashion his own likeness but also to reveal his psychological disposition. The planes of his face and texture of his hair are boldly hatched in contours of expressive brushstrokes which, despite their feverish energy, hold together as a tightly drawn portrait. The psychological intensity of the image unwinds from his eyes like a wave discharging its energy through the swirling strokes of his jacket and into the turbulent flow of the background. Today we see this painting as one of the most powerful psychological portraits in the history of art but Van Gogh viewed his work in a less intense light. He wrote about this portrait in a letter to his brother Theo, "Today I’m sending you my portrait of myself, you must look at it for some time – you’ll see, I hope, that my physiognomy has grown much calmer, although the gaze may be vaguer than before, so it appears to me." [1]. This is why Van Gogh is so universally loved. He paints with such instinctive honesty and vulnerability that he is unaware of what he is actually revealing about himself.

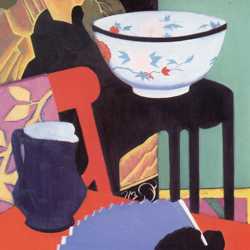

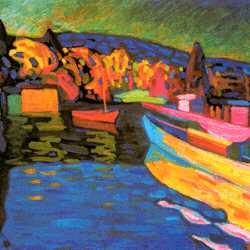

KARL SCHMIDT-ROTTLUFF (1884-1976)

Self Portrait, 1906 (oil on canvas)

Van Gogh's vigorous painting technique was a major influence on the paintings of Karl Schmidt-Rottluff. His forceful style provided the inspiration for Schmidt-Rottluff to push his own art towards the psychodrama of Expressionism. Although Schmidt-Rottluff's vivid Expressionist palette may be more strident and his impasto brushwork more energetic than Van Gogh's, he disappointingly reveals less of himself than you might expect. His use of visual elements is heightened for expressive impact but he is too consciously aware of their aesthetic effect. Consequently the result lacks the endearing candour of Van Gogh's portrait. It is, however, the type of painting that advances the canon of art by developing new expressive possibilities for color and texture. Its radical technique offers subsequent generations the licence to abstract these elements as separate aesthetic components in their own right.

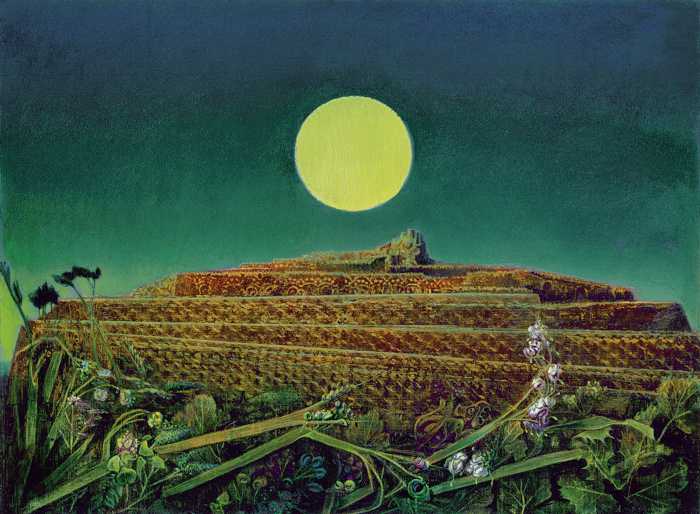

MAX ERNST(1891-1976)

The Entire City, 1935-36 (oil on canvas)

Max Ernst used the physical texture of surfaces as a source of Automatism, a device used in Surrealism to unlock the 'unconscious mind'. To this end he devised various techniques such as 'frottage' [2] and 'grattage' [3] to transfer textures onto paper and canvas. In 'The Entire City' he creates a textured surface by scraping paint over a canvas that has been laid upon planks of wood and wire mesh. The resultant texture is then searched as a potential source of images, similar to the way that psychologists use Rorschach blots.

In this work Ernst uses 'grattage' to unearth a form that evokes the terraced architecture of an ancient civilization. He then develops this idea with a painted sky for a background and flowers and plants for a foreground. The processes that Ernst employs combine a range of techniques that generate a Surrealist vision: an image born in the 'unconscious mind' and raised to consciousness through the 'free association' of Automatism.

JOAN EARDLEY (1921-1963)

Seeded Grasses and Daisies, September, 1960 (oil on board with grasses and seedheads)

Joan Eardley was an extraordinary Scottish painter whose style ranged from kitchen sink realism to expressive abstraction. Her subjects also ranged between the urban and the rural: from the gritty humanity of her portraits of children amidst the post-war slums of Glasgow to her powerful landscapes and seascapes of Catterline on the north east coast of Scotland.

Joan Eardley painted her Catterline landscapes outdoors come hail, rain or shine. She would often work on several paintings in the same location, gradually building up an awareness of her surroundings. It was her desire to paint what she felt about the landscape and not simply to represent what she saw in it. This involved getting to know a location over a period of time so that she was sensitive to its changing character. She would then try to focus on those key elements that contributed to the emotional impact of the landscape. In 'Seeded Grasses and Daisies, September', her total immersion in the subject led her to incorporate stalks of meadow grass and flowers in order to ground the abstract texture of the work in reality. Here, the image and its medium literally become one and the same.

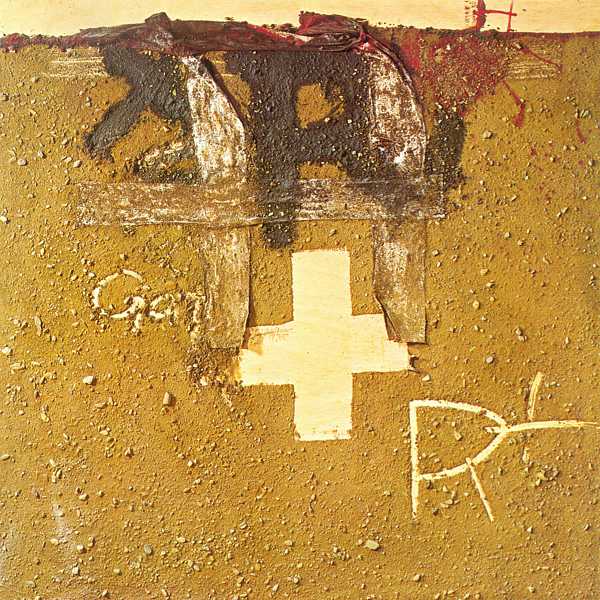

ANTONI TÀPIES (1923-2012)

Cruz y Tierra (Cross and Earth), 1975 (mixed media)

Antonio Tàpies saw texture as a language 'of great expressive forcefulness' that had not been fully explored in art. He experimented by mixing building materials such as sand, cement, marble dust, tar and straw with his paints. He combined these unrefined media to create a weathered, impasto surface into which he scratched, carved and collaged enigmatic evidence of the human presence.

Tàpies viewed his paintings as walls with all their metaphorical layers of meaning: the inscribed marks and ciphers of humanity; declarations of love and hate; bloodstained scars of violence and disorder; separation and confinement; construction and destruction; the elements of nature; smooth, serene, tortured, broken and repaired surfaces; the romantic ruins of a crumbling civilization; a witness to the passage of time and the physicality of matter.

'A cross could be a shape for expressing something spacious; such as the coordinators of space. That could be called its first significance or its first relevance. A cross could equally stand for crossing something out. It could also be a sign of obstruction. An overturned cross, an X so to speak, could be the symbol of mystery, something for the other side. Then I could paint a cross in such a way that a connection is made between two bars, and in doing so convert it into a symbol of the unlimited. So, many different crosses and X symbols occur in my works.' [4]