Dadaism - Art and Anti Art

Dadaism or Dada was a form of artistic anarchy that challenged the social, political and cultural values of the time.

MAN RAY (1890-1976)

'Cadeau (Gift)' 1921 (Flat Iron with Brass Tacks)

Dadaism or Dada was a form of artistic anarchy born out of disgust for the social, political and cultural values of the time. It embraced elements of art, music, poetry, theatre, dance and politics. Dada was not so much a style of art like Cubism or Fauvism; it was more a protest movement with an anti-establishment manifesto.

The Spirit of Dada

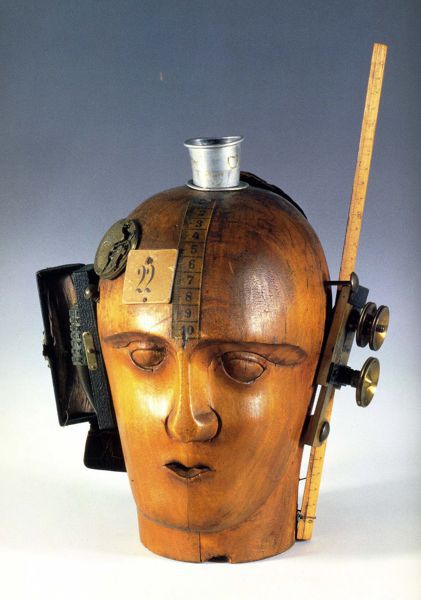

RAOUL HAUSMANN (1886-1971)

'The Spirit of Our Time', 1920 (assemblage)

The ‘Spirit of Our Time’ is a sculptural metaphor for the inability of the establishment to inspire the changes necessary to rebuild a better Germany. It is a satirical illustration of Raoul Hausmann’s statement that the average supporter of what he considered to be a corrupt society “has no more capabilities than those which chance has glued to the outside of his skull; his brain remains empty”. This blockhead of a hat maker’s dummy can only experience that which can be measured by the range of mechanical equipment attached to the outside of his head - a ruler and tape rule, the movement of a pocket watch, a jewellery box containing a typewriter wheel, some brass knobs from a camera, a leaky telescopic beaker of the kind that was issued to German soldiers during the World War 1, and an old purse nailed to the back of his head. With his eyes deliberately left blank, the ‘Spirit of Our Time’ is a blind automaton whose blinkered attitude excludes any possibility of creative thought.

The Dadaists at the Cabaret Voltaire

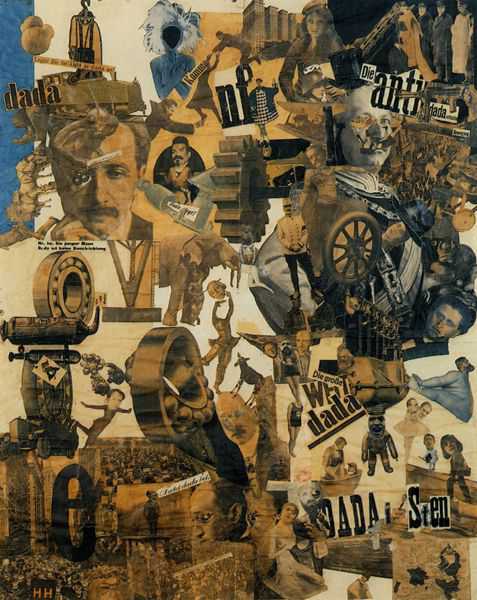

HANNAH HÖCH (1889-1978)

'Incision With The Dada Kitchen Knife Through Germany's Last Weimar Beer Belly Cultural Epoch' 1920 (Collage)

Cabaret Voltaire

During World War 1 many artists, writers and intellectuals who were opposed to the war sought refuge from conscription in Switzerland. Zurich was a melting pot for these exiles and it was there on February 5th, 1916 that the writer Hugo Ball and his partner Emmy Hemmings opened the 'Cabaret Voltaire', a rendezvous for the more radical element of the avant-garde. This venue was a cross between a night club and an arts centre where artists would exhibit their work to a backdrop of experimental music, poetry, readings and dance.

Among the original contributors to the 'Cabaret Voltaire' were Jean (Hans) Arp, Tristan Tzara, Marcel Janco and Richard Huelsenbeck. Their initial 'performances' were relatively conventional but they became increasingly dissident and anarchic in response to the carnage of World War 1. They saw the unremitting slaughter as the undeniable proof that the nationalist authorities on both sides had failed society and that the system was corrupt. United in their protest against the war and in their opposition to the establishment, 'they banded together under the battle cry of DADA!!!!'

Although the Dadaists were united in their ideals, they had no unifying style. Between 1917-1920 the Dada group attracted many different types of artists including Raoul Hausmann, Hannah Höch, Johannes Baader, Francis Picabia, George Grosz, John Heartfield, Max Ernst, Marcel Duchamp, Beatrice Wood, Kurt Schwitters, and Hans Richter.

Anti-War, Anti-Establishment and Anti-Art

Dada's weapons of choice in their war with the establishment were confrontation and provocation. They attacked traditional artistic values with irrational attitudes and provoked conservative complacency with outrageous statements and actions. They also launched a full scale assault on the art world which they saw as part of the system. It was considered equally culpable and consequently had to be toppled. Dada questioned the value of all art and whether its existence was simply an indulgence of the bourgeoisie.

The great paradox of Dada is that they claimed to be anti-art, yet here we are discussing their artworks. Even their most negative attacks on the establishment resulted in positive artworks that opened a door to future developments in 20th century art. The effect of Dada was to create a climate in which art was alive to the moment and not paralysed by the traditions and restrictions of established values.

The Dada Title Fight

Art movements are usually named by critics but Dada was the only movement to be named by the artists themselves. However, the authorship of the name has long been contested and there is no hard evidence to support any individual claim. When Hans Richter joined the group in 1917, he assumed that 'Da-Da' was taken from the Romanian language of Tzara and Janco and meant 'Yes-Yes' - an enthusiastic and positive affirmation of life. Another and more often accepted version was that Richard Huelsenbeck and Hugo Ball discovered the word while looking in a French/German dictionary. In French, 'Dada' means 'hobbyhorse' and they chose it for its childishness and naïvety. Ball stated, 'What we call Dada is foolery, foolery extracted from the emptiness in which all higher problems are wrapped..........'

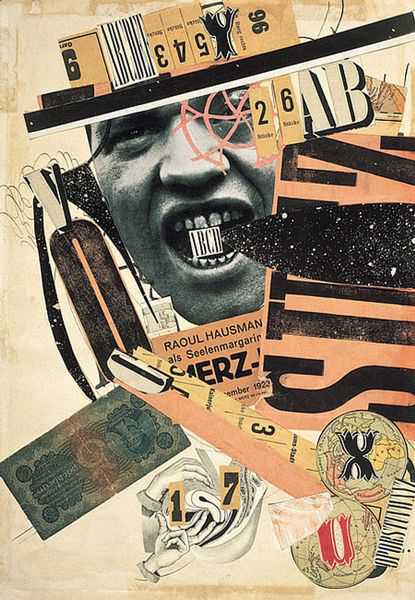

RAOUL HAUSMANN (1886-1971)

'ABCD' 1920 (collage)

Raoul Hausmann's 'ABCD' is a typical Dada collage which he described as a 'poster poem'. It is a visual counterpart to the Dada 'sound-poems' that were heard at the 'Cabaret Voltaire'. In 1916 Hugo Ball proclaimed, "I created a new species of verse, 'verse without words', or sound poems....". However, it would be more generous to attribute their inspiration to Filippo Tommaso Marinetti of the Italian Futurists and Hausmann acknowledges this debt by including the letters 'VOCE', the Italian word for voice. The word 'MERZ', which appears on a ticket in the centre of the collage, refers to the art of Kurt Schwitters who was a co-exhibiter with Hausmann in the early years of Dada. The Czech banknote in the bottom left hand corner is a souvenir from their visit to Prague where they performed a joint recital of Hausmann's sound poem, 'fmsbwtözäupggiv-..?mü'

When you first look at this work your eye is immediately drawn to its main theme: the letters 'ABCD' which are clamped in the teeth of a photographic self portrait. A spiralling arrangement of ticket stubs and typographic elements frame the artist's head. It is difficult to ignore the communicative power of the letters and numbers and you cannot help but enter into a dialogue in an attempt to make sense of them. It's an impossible task but there are just enough recognizable elements to keep your curiosity engaged. The text on the 'MERZ' ticket translates as 'Raoul Hausmann as Emotional Margarine', a sarcastic comment on the Expressionists' painting technique.

Dada Manifestos and Magazines

'DER DADA NO.2' 1919 (magazine cover)

Edited by Raoul Hausmann, John Heartfield, and George Grosz.

A series of 'manifestos' and magazines that attacked the compliant social, political and cultural attitudes that failed to oppose the war was among the range of activities that the Dadaists used to proclaim their principles.

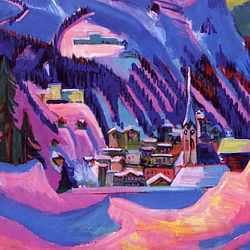

Expressionism, the most recent of the avant-garde movements, was quickly accepted and absorbed by the mainstream. It had proved to be ineffectual in bringing about the level of change that the Dadaists desired. The Expressionists were inward looking and nationalistic, steeped in a German Gothic past. They were part of the problem. In the Berlin Dada Manifesto of 1918, Richard Huelsenbeck launched a scathing attack on the impotence of Expressionism, ‘Expressionism wanted inwardness, it conceived of itself as a reaction against the times, while Dadaism is nothing but an expression of the times. Dada is one with the times, it is a child of the present epoch which one may curse, but cannot deny..........Under the pretext of inwardness the Expressionist writers and painters have closed ranks to form a generation which is already expectantly looking forward to an honourable appraisal in the histories of art and literature and is aspiring to honours and accolades..........Expressionism is not spontaneous action. It is the gesture of tired people who wish to escape themselves and forget the present, the war and the misery..........The Expressionists are tired people who have turned their backs on nature and do not dare look the cruelty of the epoch in the face. They have forgotten how to be daring. Dada is daring per se, Dada exposes itself to the risk of its own death. Dada puts itself at the heart of things. Expressionism wanted to forget itself, Dada wants to affirm itself.’

Berlin Dada

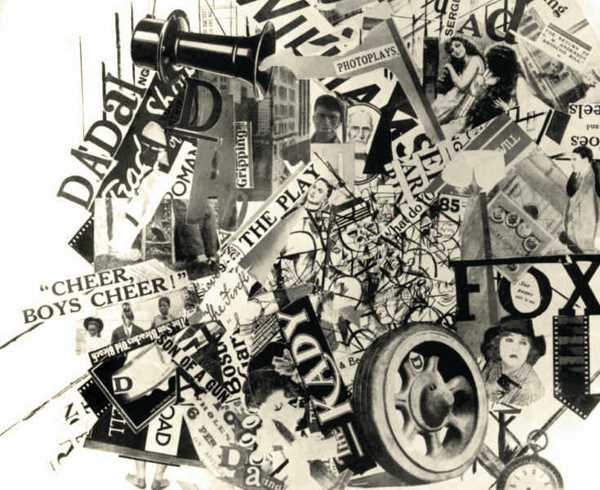

GEORGE GROSZ (1893-1959) and JOHN HEARTFIELD (1891-1968)

'Life and Work in Universal City, 12:05 Noon', 1919 (photomontage)

After the war, the face of Dada began to change. Many of the Dadaists who were exiles in Zurich began to drift back to their home countries and found that life was quite different there. As they relocated to Berlin, Cologne, Hanover and some as far as New York, Dada developed an international reputation but each of these venues had its own distinctive style inspired by the artists who settled there.

In post-war Berlin, Dada became less anti-art and adopted a more political stance. Reality bit hard as the war-weary population struggled to survive the effects of economic meltdown. There was social and political disorder as Left fought Right for control of the government. In this climate the irreverent posturing of Zurich Dada would have been totally inappropriate, so Dada in Berlin emerged with a harder hitting punch.

Raoul Hausmann, Hannah Höch, John Heartfield and George Grosz were the main artists who developed the strident political satire of Berlin Dada. The technique that most of them trusted to deliver their disparaging commentary was photomontage: a collage of photographs and text cut from contemporary newspapers and magazines. The immediacy of this photographic imagery added an air of authority to their work by physically linking their ideas to the real world. The layout of these works was influenced by the flattened and fragmented arrangements of Cubism and Futurism.

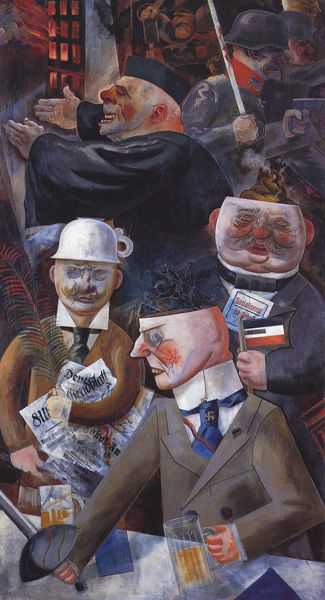

GEORGE GROSZ (1893-1959)

'The Pillars of Society' 1926 (oil on canvas)

The work of George Grosz gradually evolved from the nihilistic protest of Dada to a more focused expression of his disgust at the cruelty and decadence of the bourgeoisie. He was a skilled painter and illustrator who managed to convey his contempt in traditional media. Grosz's vitriolic drawings and paintings exposed the hypocrisy of the politicians, the press, the army, the ruling classes and their corrupt clergy. His work simply held up a mirror to their behaviour in order to reflect their vices. Grosz wrote, "Man has created an insidious system - a top and a bottom. A very few earn millions, while thousands upon thousands are on the verge of starvation. But what has this to do with art? Precisely this, that many painters and writers, in a word, all the so-called 'intellectuals' still tolerate this state of affairs without taking a stand against it......To help shake this belief and to show the oppressed the true faces of their masters is the purpose of my work".

'The Pillars of Society' (1926) is a group portrait that manages to portray 'all the true faces of their masters' in one room. In medieval art, saints were painted carrying symbolic attributes to help identify them to the illiterate. For example, Saint Peter was usually depicted holding keys as Christ told him "I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven". Grosz updates this device with an outrageous dose of irony to identify his oppressors.

In the foreground we have a German officer wearing a monocle and a swastika which, in 1920, was adopted as the symbol of the Nazi party. He has a cruel face with duelling scars on his cheek and a thin slit of a mouth aggressively exposing his teeth. The attributes that he carries are a glass of beer and a sabre, symbols that expose him as a drunken warmonger. However, he is blind to his own brutality as he sees himself as a gallant hussar, illustrated by the delusional thoughts coming out of his head.

Behind him on the left is a portrait of Alfred Hugenberg, the press baron, who is wearing a chamber pot engraved with an Iron Cross as a hat. This symbolizes both the bias of his newspapers and Grosz's opinion of them. His attributes are a pencil for writing articles and a blood stained palm. Historically the palm is a symbol of peace, but stained with the bloody consequences of his newspapers' propaganda, it becomes a symbol of hypocrisy.

Behind him on the right is a portrait that looks remarkably like Friedrich Ebert, the leader of the Social Democratic Party and the first President of Germany from 1919-1925. His attributes are a leaflet that reads, "Socialism is Working" and a flag of the Weimar Republic. Grosz leaves no doubt as to what he thinks of his policies by giving him a pile of steaming faeces for brains.

At the rear of this work is a clergyman whose sanctimonious face is flushed with the long term effects of alcohol. With closed eyes he preaches from the safety of his room, blind to the reality of the burning city outside his window and ignoring the brutality of the civil war that unfolds behind his back.

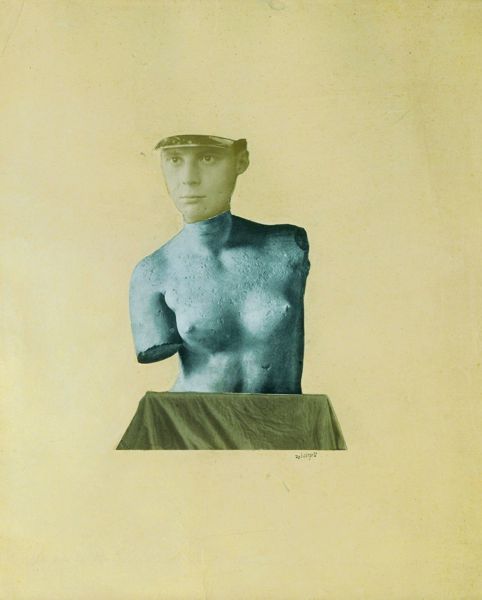

JOHANNES THEODOR BAARGELD(1892 -1927)

'Typical Vertical Misrepresentation as a Depiction of the Dada Baargeld' 1920 (photomontage)

In Cologne, Max Ernst and Johnannes Baargeld were the founding members of Gruppe D (D for Dada) whose 1920 exhibition 'Dada-Vorfrühling' (Dada-Early Spring) caused a public outrage and was closed by the police. The show was held in a pub where the public had to enter through the men's toilet where they were confronted by a row of urinals and a woman in a communion dress reciting obscene poems. They also encouraged visitors to smash up certain exhibits and provided them with a hammer to do so, enlisting their participation in the 'anti-art' spirit of Dada.

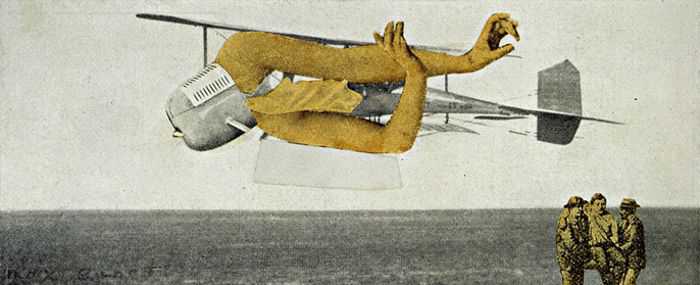

MAX ERNST (1891-1976)

'Murdering Airplane' 1920 (photomontage)

Max Ernst, like most of the great artists associated with Dada, saw imaginative possibilities in the techniques that the Dadaists employed for their 'anti-art' activities. Where Hausmann and Heartfield had used the fragmented imagery of photomontage as a vehicle for political satire, Ernst took a more lyrical approach by creating a visual poetry built from the unconscious associations of juxtaposed images. He summed up his collage technique as 'the systematic exploitation of the chance or artificially provoked confrontation of two or more mutually alien realities on an obviously inappropriate level - and the poetic spark which jumps across when these realities approach each other'.

Between 1919 and 1920, Ernst produced a series of collages where he combined illustrations of militaria with human limbs and various accessories to create an assortment of strange hybrid creatures. The weapons and technology that he chose for these works must have had a fearful resonance for both the public and Ernst himself as he served in the artillery during the war where was injured by the recoil of a field gun.

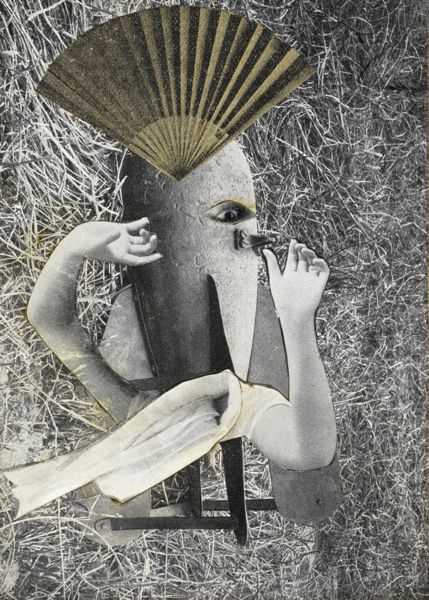

MAX ERNST (1891-1976)

'The Chinese Nightingale' 1920 (photomontage)

In 'The Chinese Nightingale', the arms and fan of an oriental dancer act as the limbs and headdress of a ridiculous creature whose body is an English bomb. An eye has been added above the bracket on the side of the bomb to create the effect of an absurd looking bird. Ernst's whimsical humour has the effect of defusing the natural fear associated with bombs. The title of the work was taken from the fairy tale by Hans Christian Andersen and the image is open to similar allegorical interpretation.

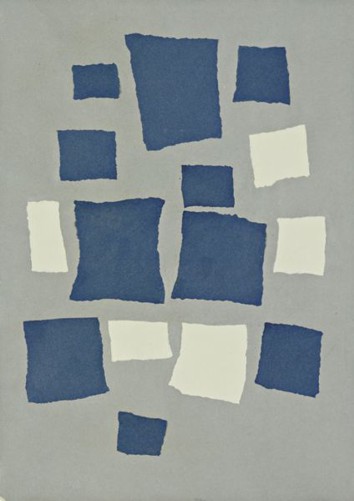

JEAN (HANS) ARP (1886-1966)

'Rectangles Arranged According to the Laws of Chance' 1917 (collage)

Jean Arp was a major artist associated with Dada in Cologne who also began to explore Dadaist techniques in a more positive and creative manner. Although his Dada credentials were beyond doubt, he was never a dyed-in-the-wool fanatic. His work is steeped in aesthetics, which most of the Dadaists would have frowned upon, but what they admired in Arp was the use of chance as an element of his art. The principle of chance was employed as an 'anti-art' device, in both Dadaist art and literature, as it overlooked the skill and craftsmanship associated with traditional artistic values.

From a pure Dada perspective, what should have happened in 'Rectangles Arranged According to the Laws of Chance' is that Arp tore up sheets of paper into rectangles and dropped them onto a larger sheet, sticking them down where they landed 'according to the laws of chance' irrespective of their aesthetic appeal. This result would have been in accordance with Dada principles. What has actually happened is that there has been some degree of positional 'tweaking' after landing to improve the aesthetic interaction between the rectangles. You can't keep a good artist down.

KURT SCHWITTERS (1887-1948)

'Construction for Noble Women' 1919 (assemblage)

Kurt Schwitters, who settled in Hanover at the end of the war, rejected the political activism of the Berlin Dadaists in favour of a more lyrical approach that 'always strives towards art'. When Hausmann proposed him for membership of Club Dada he was rejected by Huelsenbeck on the grounds that he was too commercially minded. Ironically, in his solo first exhibition at the Galerie Der Sturm, Schwitters began to title his works 'Merz' - an abbreviation of 'Kommerz' (Commercial) - coined from a torn fragment in one of his collages which was originally part of a letterhead from the Kommerz-und Privatbank.

Kurt Schwitters created hundreds of 'Merz' collages and assemblages. These works were influenced by Cubism and Constructivism but were purely abstract with all representational references removed. Any need for representation was superseded by the physical reality of the source material that he selectively gathered from the street. He carefully crafted his 'Merz' pictures from a palette of junk with elements chosen for their shape, color, pattern, texture or form. It was Schwitters' choice of materials that linked him to Dada more than any 'anti-art' philosophy. Robert Hughes, the art critic, eloquently describes the allusions conjured up by Schwitters' 'Merz' works, "So many people and so many messages: so many traces of intimate journeys, news, meetings, possession, rejection, with the city renewing its fabric of transaction every moment of the day and night, as a snake casts its skin, leaving the patterns of the lost epidermis behind as "mere" rubbish."

New York Dada

FRANCIS PICABIA (1879-1953)

'Love Parade' 1917 (oil on cardboard)

New York was another popular centre for artistic exiles during WW1. Francis Picabia, a French painter associated with the Cubism, first visited New York in 1913 for the opening of the Armory Show, a major exhibition of contemporary art from Europe and America. Having independent means, he was able to spend the war years travelling between Europe and America promoting modern art.

While living in New York Picabia became fascinated by the myth of the machine as symbol of modernity. He expresses this in his 'portraits mécaniques', a series of absurd fantasies which present mechanical contraptions as a metaphor for human relationships. In an article from the New York Tribune he states, "The machine has become more than a mere adjunct of life. It is really a part of human life...perhaps the very soul...I have enlisted the machinery of the modern world, and introduced it into my studio.”

In 1915 Picabia was visited by his friend, Marcel Duchamp, and together with the American artist Man Ray (Emmanuel Radnitzky) whose assemblages 'Cadeau' and 'Object to be Destroyed' are illustrated at the top and bottom of this page, formed the backbone of Dada in America.

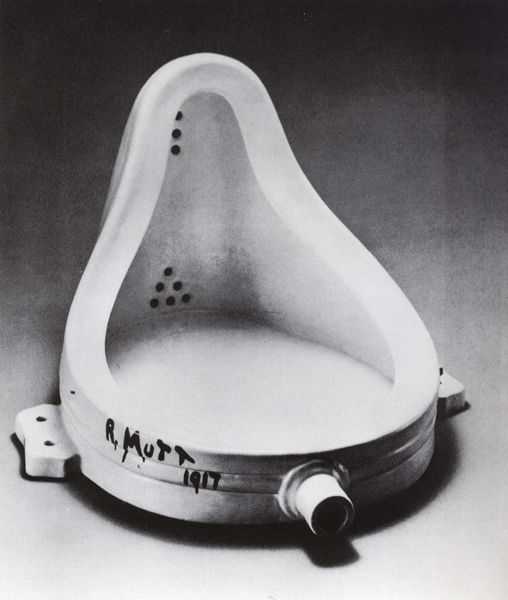

MARCEL DUCHAMP (1887-1968)

'Fountain' 1917 (ready-made)

When Marcel Duchamp arrived in New York he discovered that he already had a reputation, albeit a notorious one, for his painting, 'Nude Descending a Staircase' which had been a source of controversy when exhibited at the Armory Show. However, another of his works was to become an even greater challenge to the artistic establishment.

In 1916, Duchamp was one of a group of artists who formed the Society of Independent Artists in New York. The following year they held their "First Annual Exhibition", a vast show which attracted around 2500 exhibitors. It was open to all who paid the entrance fee with the guarantee that their work would be exhibited - all but one: Marcel Duchamp.

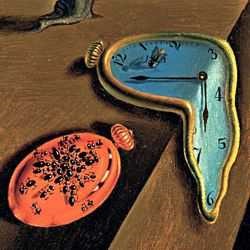

Duchamp's exhibit was a sculpture entitled "Fountain" which was signed with the pseudonym R. Mutt and was the only work to be barred from the exhibition. In effect "Fountain" was a white porcelain urinal that had been lifted straight off the factory shelf and placed on a plinth as an artwork. By signing the object, Duchamp was declaring it to be a work of art and challenging the establishment's position on what could be considered as art. Duchamp believed that everyone had the potential to be an artist and that everything had the potential to be interpreted as art. Through the eyes of Dada all art of the past had been discredited and "Fountain" was the declaration of a new democracy which entitled artists to widen their frame of reference in their quest to draw meaning from the world.

Duchamp produced other sculptures that were conceptually similar to "Fountain" which he referred to as 'ready-mades'. Among these were a ''Bottle Rack''; a "Bicycle Wheel" mounted on a wooden stool and a snow shovel which was hung from the ceiling and titled, "In Advance of The Broken Arm".

The Legacy of Dada

MARCEL DUCHAMP (1887-1968)

'L.H.O.O.Q', 1919 (ready-made)

In Berlin, 'The First International Dada Fair' (1920) was the only attempt to document all the aspects of Dada on an international scale. Although the exhibition was packed with provocative material which gave rise to several prosecutions, it was essentially a flop as the public had lost interest. From 174 catalogued exhibits there was only one sale. Dada had lost its shock value in a post-war culture where the harsh realities of life had numbed the public's sensibility. Ironically, The First International Dada Fair' was the beginning of the end.

The DNA of Dada was self destructive. The Dadaists had condemned cultural conformity but the paradox is that any revolution eventually becomes a conformity in itself. Artists have a basic need to create but the inherent negativity of by Dada's 'anti-art' dogma must eventually limit their creative potential. There were many good artists in Dada who could see that possibility and the best of them adapted the innovative techniques of Dada to their own ends.

By the end of 1920, most of the main protagonists had migrated to Paris where Dada had a short-lived swan song. However, unlike Zurich and Berlin where there was a predisposition towards ideological unity, there were now elements of individuality that were calling for a more positive philosophy which would shortly materialize as Surrealism.

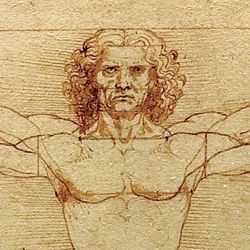

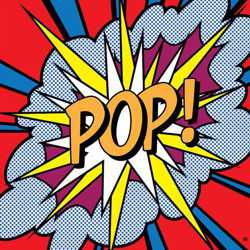

Although Dada only lasted for a few years its impact was considerable. The Dadaists introduced and explored techniques and concepts that we take for granted in art today: automatism, chance, photomontage, assemblage, and the idea that an artwork could be a temporary installation. They also expanded the boundaries and context of what was considered acceptable as art, which in turn inspired future developments such as Action Painting, Pop Art, Happenings, Installations, Conceptual Art and its various post-modern splinter groups.

Dadaism Notes

MAN RAY (1890-1976)

'Object to be Destroyed', 1923 (ready-made)

Dada was a form of artistic anarchy that challenged the social, political and cultural values of the time.

-

Dada embraced elements of art, music, poetry, theatre, dance and politics.

-

Dada aimed to create a climate in which art was unrestricted by established values.

-

Dada was anti-establishment and anti-art.

-

The name 'Dada' means 'hobbyhorse' or the exclamation "Yes-Yes".

-

The Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich was the birthplace of Dada.

-

After the war the Dadaists relocated to Berlin, Cologne, Hanover and New York.

-

The Dadaists published 'manifestos' and magazines to help communicate their ideas.

-

The Dadaists used techniques such as automatism, chance, photomontage and assemblage.

-

The Dadaists introduced the concept that an artwork could be a temporary installation.

-

The Dadaists expanded the boundaries and context of what was considered acceptable as art.

-

Several Dada exhibitions caused public outrage and were closed by the authorities.

-

Dada influenced the development of Surrealism, Action Painting, Pop Art, Happenings, Installations and Conceptual Art.

-

The main artists associated with Dada were Hugo Ball, Tristan Tzara, Marcel Janco, Richard Huelsenbeck, Jean (Hans) Arp, Raoul Hausmann, Hannah Höch, John Heartfield, Kurt Schwitters, Johannes Baargeld, Johannes Baader, Max Ernst, George Grosz, Hans Richter, Francis Picabia, Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp.