Italian Renaissance Art - Naturalism

Naturalism in Renaissance art was inspired by the lifelike accuracy of Classical sculpture, a quality that had disappeared from artistic representation during the Dark and Middle Ages.

GIOTTO (c.1267-1337)

'The Lamentation', 1303-05 (Fresco 72"x72")

Scenes from the Life of Christ in the Arena Chapel, Padua.

Naturalism in Renaissance art was inspired by the lifelike accuracy of Classical sculpture, a quality that had disappeared from artistic representation during the Dark and Middle Ages.

Elements of naturalism began to reappear during the Proto-Renaissance in the paintings of Giotto. In contrast to the flat, formal figures of Byzantine art, Giotto introduced more lifelike forms whose eye contact, expressions, postures and gestures conveyed an unprecedented range of emotions. They were also composed within an organized space where overlapping figures suggested the illusion of depth and constructed a narrative flow.

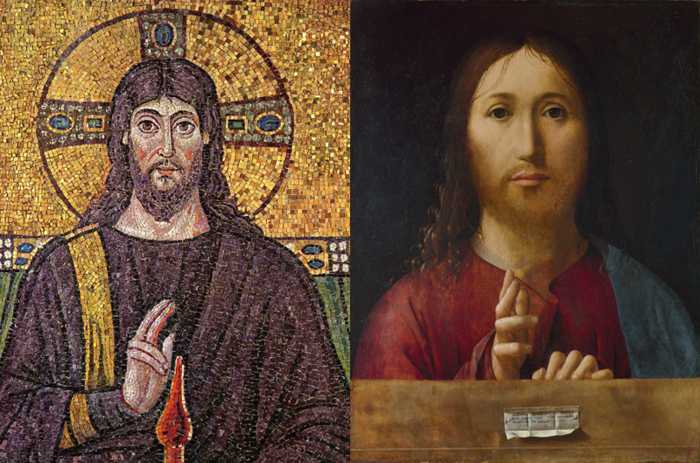

'CHRIST BLESSING'

Left: 'Christ Pantocrator', Byzantine Mosaic (6th century)

Right: 'Christ Blessing' by Antonello da Messina (1465), Oil on Panel

You can see the considerable development of naturalism between Byzantine and Early Renaissance art in the two images of Christ. In Byzantine art, he is depicted as the stylized image of 'Christ Pantocrator' (trans. Almighty or All Powerful), a majestic figure who wears a halo adorned with jewels and highlighted against a background of gold leaf mosaic. In Renaissance painting he is portrayed as the humble figure of Jesus, a naturalistic flesh and bones figure in contemporary clothing to help the common man to identify with his faith.

Naturalistic Drawing: The Study of Anatomy and Nature

Michelangelo (1475-1564)

LEFT: 'Studies for the Libyan Sibyl', c.1510-11 (red chalk drawing)

RIGHT: 'The Libyan Sibyl', c.1510-11 (fresco)

The necessary skills to achieve the exceptional quality of naturalism that we see in High Renaissance art were developed by observational drawing, particularly through the first-hand study of anatomy and nature. We can see the outcome of this development when we look at Michelangelo's sketches for the 'Libyan Sibyl' alongside the finished work from the Sistine Chapel ceiling.

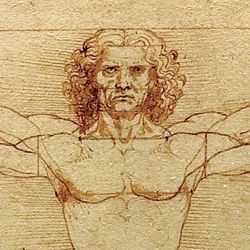

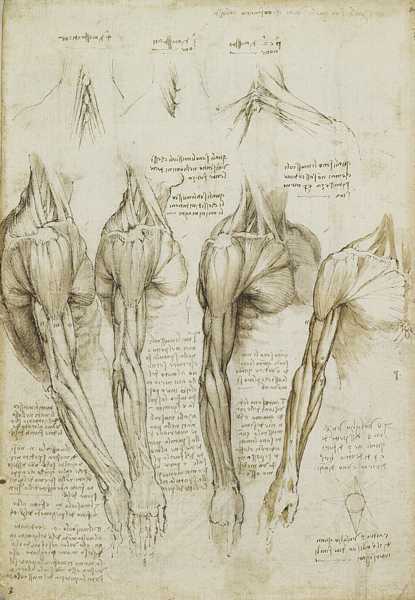

LEONARDO DA VINCI (1452-1519)

'Anatomical study of the muscles of the shoulder, arm and neck', c.1510-11

(pen, ink and wash)

In their endeavour to match the naturalism of Classical beauty, many Renaissance artists took up the study of anatomy to increase their knowledge of the human form. Some, like Leonardo, even went to the extent of dissecting dead bodies to explore the structures that lay beneath the skin.

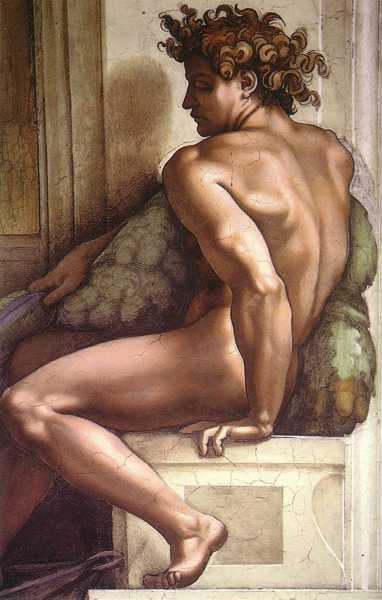

Michelangelo (1475-1564)

'Ignudi detail from the Sistine Chapel Ceiling', c.1508-12

(fresco)

Others like Michelangelo, were not only fascinated by the natural beauty of the human body but also used its expressive power as an emotive force in their work. As the anatomical knowledge of artists increased, the clothes on their models subsequently decreased and the nude returned as an acceptable subject in art for the first time since Antiquity.

LEONARDO DA VINCI (1452-1519)

'The Virgin of the Rocks', 1483-85

(oil on poplar panel)

A greater awareness of natural sciences such as botany and geology enhanced the scenic elements of an artwork to counterbalance the greater naturalism of figures and create a unified composition. You can see how Leonardo uses his knowledge of both these sciences to embellish the foreground of 'The Virgin of the Rocks' with botanical studies and enhance the mystical mood of its background with imaginative rock formations.

The invention of oil paint was another factor that made such a heightened level of naturalism possible. This new medium could produce an intense array of colors, subtle blends of tone and unprecedented detail. Artists were now able to create more lifelike forms with an atmospheric depth that was enhanced by their observation and understanding of natural light and shade.

Linear Perspective

Perugino (1483-1520)

'Christ Giving the Keys of the Kingdom to St. Peter', 1509-11

(Sistine Chapel fresco)

In the Early Renaissance, one aspect of naturalism in art was related to the problem of arranging the figures and buildings in a landscape to create the illusion of depth. A mathematical solution to this was discovered around 1413 by Leon Baptista Alberti (1404-72) and Filippo Brunelleschi (1377-1446) when they developed the laws of linear perspective, one of the key innovations in Renaissance art. Perspective drawing allowed artists to accurately portray the 3-dimensional world on a 2-dimensional surface from a fixed point of view. In Perugino's painting of 'Christ Giving the Keys of the Kingdom to St. Peter', we can see how the receding lines of perspective, created by the courtyard grid, all converge at a vanishing point on the horizon, which is both the eye level of the artist (and viewer) and the center of their viewpoint.

Beauty and Harmony

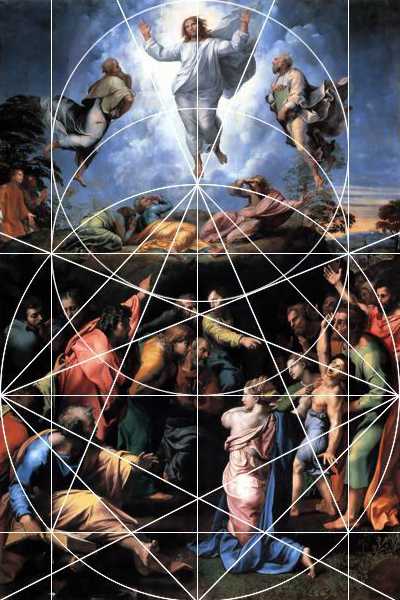

RAPHAEL (1483-1520)

'The Transfiguration', 1516-20 (oil painting) [1]

During the High Renaissance, Naturalism was more concerned with refining the form of the figure within an authentic looking background and combining these in a composition of harmonic proportions. The Ancient Greeks saw mathematics as the foundation of beauty and harmony and many Renaissance artists incorporated this concept into their compositions. The artist whose paintings best combine the key elements of High Renaissance art was Raphael. His style merged the intellectual rigour of Leonardo, the expressive power of Michelangelo and the noble forms of Classical sculpture to achieve what Vasari called 'the ultimate perfection' - a refined and dramatic harmony of the visual elements of art.

The Renaissance process of observing, recording and refining the naturalism of an image became the standard approach to drawing and painting for the next four hundred years.