The Visual Elements - Shape

Shapes can be used in art to control your feelings about the mood and composition of an artwork.

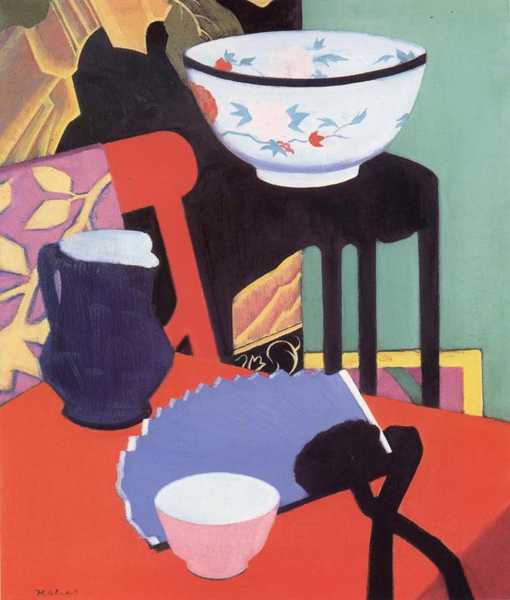

FRANCIS CAMPBELL BOILEAU CADELL (1883-1937)

The Blue Fan, 1922 (oil on canvas)

The Visual Element of Shape can be natural or man-made, regular or irregular, flat (2-dimensional) or solid (3-dimensional), representational or abstract, geometric or organic, transparent or opaque, positive or negative, decorative or symbolic, colored, patterned or textured.

The Perspective of Shapes: The angles and curves of shapes appear to change depending on our viewpoint. The technique we use to describe this change is called perspective drawing.

The Behaviour of Shapes: Shapes can be used to control your feelings in the composition of an artwork:

-

Squares and Rectangles can portray strength and stability

-

Circles and Ellipses can represent continuous movement

-

Triangles can lead the eye in an upward movement

-

Inverted Triangles can create a sense of imbalance and tension

Our selection of artworks illustrated below have been chosen because they all use shape in an inspirational manner. We have analyzed each of these to demonstrate how great artists use this visual element as a creative force in their work.

Two-Dimensional Shapes

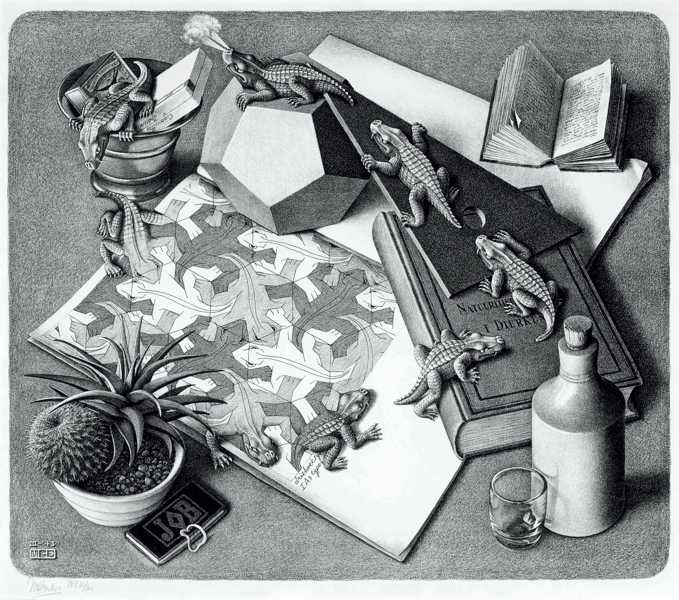

M. C. ESCHER (1898-1972)

Reptiles, 1943 (lithograph)

Two-dimensional shapes: Most of the art we see is two-dimensional: a drawing, a painting, a print or a photograph which is usually viewed as a flat surface. Most two-dimensional art tries to create the illusion of three dimensions by combining the visual elements to a greater or lesser degree.

In Escher's lithograph, the artist is playing with the illusion of two and three-dimensions in the same image. From an interlocking pattern drawn on a page of his sketchbook, the flat outlined shapes of the reptiles are brought to life by the addition of tone. They step out of their two-dimensional world into a three dimensional landscape of solidly rendered objects that have been selected for their variety of shapes and textures. After a short journey exploring this new environment they return to their original format by losing their tone and adopting their former position within the design - a return trip between two and three dimensions.

ANTHONY CARO (1924-2013)

Paul's Turn, 1971 (cor-ten steel)

Three-dimensional shapes: Anthony Caro uses industrial beams, bars, pipes, sections and steel plate which he cuts, bends, welds, bolts and occasionally paints to form the shapes for his constructed metal sculptures. You can walk around and between these three dimensional abstract forms to interact with the changing relationships of their delicately balanced structures.

Although this sculpture is constructed from heavy gauge steel and probably weighs about the same as an average family car, it seems to defy gravity. The open arrangement of its composition and the delicate balance of its component parts collaborate to lift this sculpture from the deadweight of its materials to its elevated status as an artwork.

Representational Shapes

HARMEN STEENWYCK (1612-1656)

'Still Life: An Allegory of the Vanities of Human Life', 1640

(oil on oak panel)

Representational shapes attempt to reproduce what we see to a greater or lesser degree.

Representational art is the blanket term we use to describe any artwork whose shapes are drawn with some degree of visual accuracy. Realism, however, is not the sole objective of representational art. It can be stylized with various levels of detail, from a simple monochrome outline to a fully rendered form with color, tone, pattern and texture. For example, compare the exquisite detail of 'Still Life: An Allegory of the Vanities of Human Life' by Harmen Steenwyck to 'The Blue Fan' by Francis Cadell at the top of the page. Both are still life paintings that use accurate representational shapes but the former evolves as an outstanding study of tone and texture while the latter abstracts and develops color as a major theme of the work.

'Still Life: An Allegory of the Vanities of Human Life' is the pinnacle of representational art. It is painted with a remarkably realistic technique but it is more than just an example of skilled craftsmanship. Each object has a unique symbolic meaning and works together to create a moral narrative within the group. To discover more about the hidden secrets of this artwork please explore our page on Harmen Steenwyck - Vanitas Still Life Painting.

'The Blue Fan' also uses accurate representational shapes which play a major role in the composition of the work but the balance of the other visual elements is altered for creative effect: tone and texture are suppressed to allow the expressive qualities of shape, color and pattern to flourish.

PAUL CÉZANNE (1881-1973)

Still Life with a Peach and Two Green Pears, 1883-87 (oil on canvas)

Abstract shapes, modified by the other visual elements, are the subject matter of Abstract Art.

When Paul Cézanne began to distort the perspective of representational shapes in his paintings, art took its first steps on a journey that led it through the partial abstraction of Cubism and Futurism to a range of pure abstract styles including Suprematism, Constructivism, De Stijl, Abstract Expressionism, Op Art and Minimalism.

In 'Still Life with a Peach and Two Green Pears' Cézanne tilts the perspective of the plate towards the picture plane. This has the effect of flattening the composition and emphasizing the abstract outline of its shapes. The flatness of the painting is further enhanced by the diamond shaped moulding and the circular handle of the cupboard in the background. Cézanne believed that the two dimensional qualities of a painting should not be denied and consequently much of his work involves:

-

creating a balanced arrangement of shapes, some of which may be distorted for the benefit of the composition.

-

defining depth and form with the natural properties of color, where warm colors appear to advance while cool colors recede.

-

adapting his painting technique by using regulated brushstrokes to emphasize the unity of surface in his work.

Cézanne was not interested in the Impressionists' attempts to imitate the fleeting effects of light and color in nature. He called his paintings 'constructions after nature' [1] where the colors and forms that he observed were reconstructed as 'something solid and durable, like the art of the museum'. [2]

Abstract artists attempt to stimulate an emotional response by arranging the visual elements in a harmonic or dynamic configuration, much in the same way that a musician uses sound, pitch, tempo and silence to compose a piece of music. A musical analogy has often been used to help describe the effect of abstract art on the viewer.

Most people find it difficult to look at an abstract image without intuitively trying to interpret it through their understanding of representational forms. When looking at abstract artworks, the viewer often needs to take a transcendent leap and open their mind to the metaphysical properties of the visual elements, embracing a more spiritual response as opposed to an analytical one.

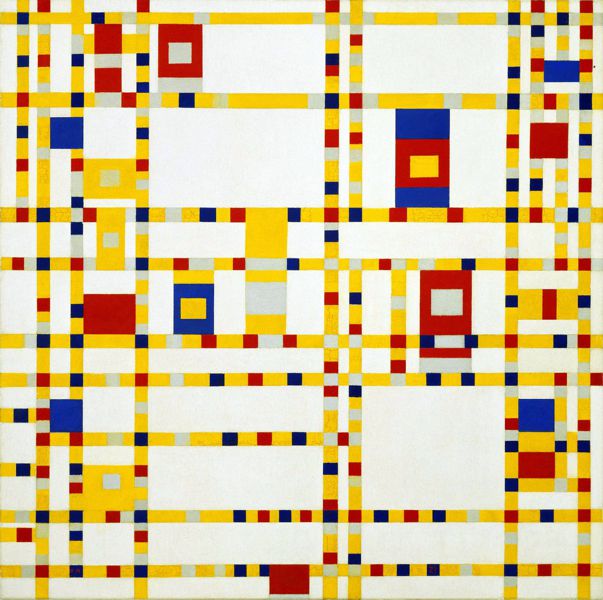

Piet Mondrian, the major artist of the De Stijl movement, was arguably the greatest exponent of 'pure' abstraction in the 20th century. Throughout many years of development he reduced the visual elements of his paintings to horizontals, verticals, rectangles and primary colors with black, white and grey. He gave his paintings objective titles such as 'Composition with Red, Yellow and Blue' to try to disconnect them from any representational interpretation. His art was an attempt to discover a new language of universal relationships whose visual harmony could somehow touch the human spirit.

One of his last great works, 'Broadway Boogie Woogie', is possibly the 'purest' of his paintings but its title paradoxically pulls us back into the realms of representation with its musical reference to Broadway in New York. Consequently it becomes very difficult to look at the work without relating it to an aerial view of the buildings and traffic flow through Manhattan. Once you have that image in your mind, the pulsing of the small squares becomes the movement of vehicles along the streets and colors such as yellow take on unintended references to New York taxis. Despite this representational distraction, it is a testament to the abstract qualities of this painting that it still retains the power to move us.

As a serious art form, pure abstraction is a rarified atmosphere. It requires the artist to look inwards with a rigorous discipline and to rely entirely on their own instincts and experience of the visual elements to inspire their creative vision. The representational artist has a far greater degree of freedom with both the natural and fabricated worlds accessible as the source of their inspiration, but the abstract artist has the unique opportunity to create something that has never been seen before. Perhaps the best art like 'Broadway Boogie Woogie' has a foot in both camps: it can create an idealized image that lifts the spirit but it also has a reassuring hold on reality.

Positive and Negative Shapes

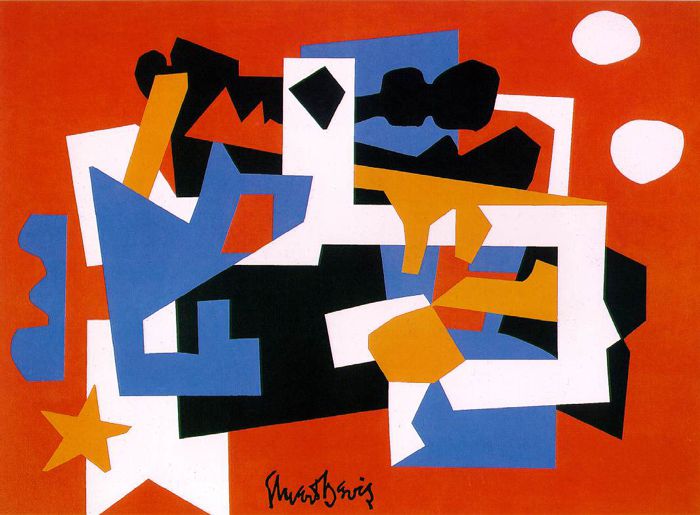

STUART DAVIS (1892-1964)

Colonial Cubism, 1954 (oil on canvas)

Positive Shape: This is the actual physical form of any shape.

Negative Shape: This the space between and around the physical form of any shape.

In 'Colonial Cubism', Stuart Davis plays with our interpretation of space by using color to subvert our reading of positive and negative shapes. He wrote, "I think of color as an interval of space - not as red or blue. People used to think of color and form as two things. I think of them as the same thing, so far as the language of painting is concerned. Color in a painting represents different positions in space." [3]

When we look at certain shapes in this work, their form appears to either advance or recede depending on their adjacent shapes and colors. Despite the fact that they are flat and on the same plane, they alternate between a positive or negative reading of their space.

There were two things that Davis loved which had a profound effect on his painting: New York and jazz. The title of this painting is a humorous reference to the ambience of New York as the inspiration for the shapes and colors of the work while acknowledging the European origins of its style. His love of jazz is reflected in the syncopated rhythm of his shapes as they oscillate between a positive and negative reading across the composition.

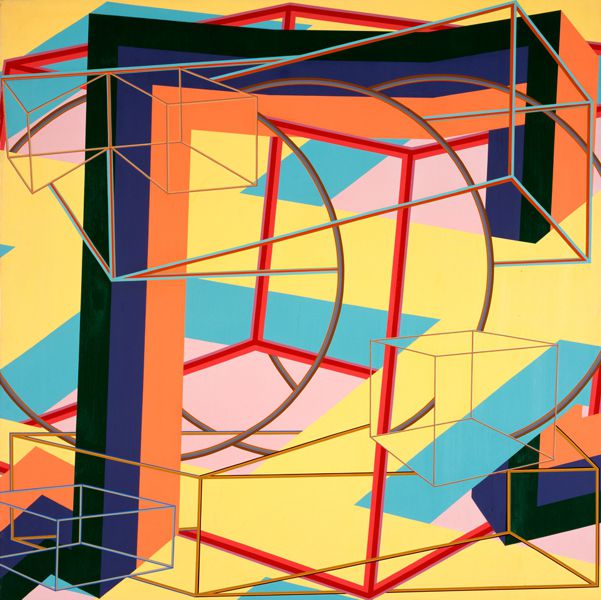

Geometric Shapes

AL HELD (1928-2005)

"S-E" 1979 (84"x84", acrylic on canvas)

Geometric shapes were originally formed mechanically using a ruler or compass. However today, even the most complex geometric forms can be easily created using digital imaging software. In art they tend to be used to convey the idea of rigidity, structure, pattern, perspective and 3 dimensional form.

The American artist Al Held, known for his 'hard-edged' style of Geometric Abstraction, is quoted in Time Magazine as saying, “We’re not going to get rid of chaos and complexity, but we can find a way to live with them.” Held's paintings, like "S-E" above, are a metaphor for this predicament. Their multiple perspectives, different scales, transparency and opacity, consistency and contradiction, all reflect the chaotic nature of our minds and our world. The way he composes the painting by cropping the activity at the edges suggests that this is but a detail of our infinite 'chaos and complexity'. Nevertheless, Held's images are not unsettling, in fact they are actually quite beautiful and inviting. Within the maze of their illusionistic geometry there is enough evidence of continuity of line and shape to keep us engaged in our search for a reassuring visual integrity.

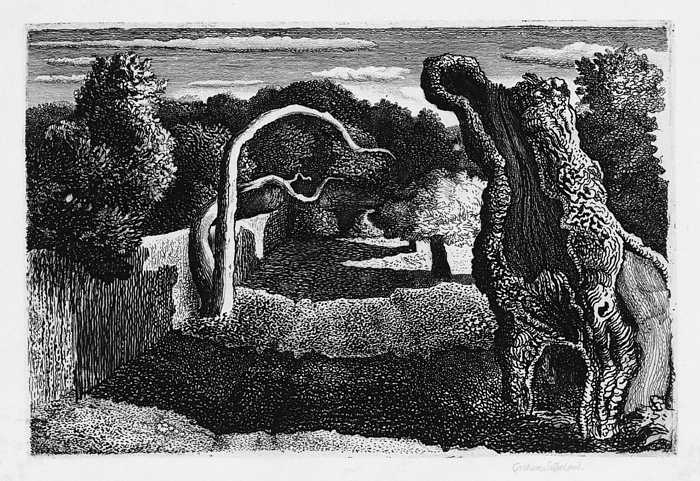

Organic Shapes

GRAHAM SUTHERLAND (1903-1980)

Pastoral, 1930 (etching)

Organic shapes are usually natural, irregular and freeform in character. You can see them in the patterns of growth and decay in nature; in the shapes of seeds, plants, leaves, flowers, fruit, trees, branches; and in the ephemeral forms of clouds and water. They are also associated with anatomical forms such as heart and kidney shapes.

Organic shapes can convey a sense of formation and development, and suggest qualities such as softness, sensuality, flexibility and fluidity.

In 'Pastoral' by Graham Sutherland, the scene is set in a walled garden with a cast of organic forms. Two ancient trees, one a hollowed out trunk, the other a bent and twisted bough, commune in the choreographed language of abstract forms. The younger members of the woodland surround these two elders like an attentive audience absorbing their wisdom and experience. The clouds add a sympathetic backdrop while the garden wall acts like a geometric counterpoint to this organic drama.

Symbolic and Decorative Shapes

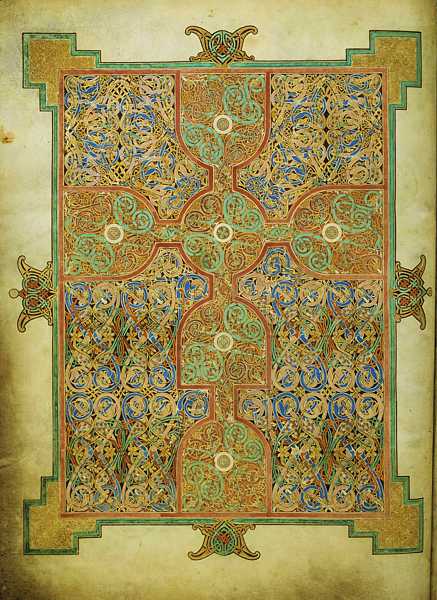

EADFRITH, BISHOP OF LINDISFARNE (died 721)

'Illuminated Ornamental Cross', 715-721,

Lindisfarne Gospels

Symbolic Shapes: A symbol is an object or sign that represents an identity, a belief, a concept or an activity. For example, the symbol of a cross can represent the Christian faith; or be an emblem of the four classical elements (earth, air, fire and water); or the four points of a compass (north, south, east and west); or the flag of Switzerland; or simply a road sign indicating crossroads.

Decorative Shapes: All decorative forms are based on either Nature or Geometry or a combination of both. Within each of these categories lies a huge range of styles that cross historical, geographic and cultural borders including Egyptian, Greek, Roman, Arabian, Turkish, Persian, Islamic, Indian, Chinese, Japanese, African, Asian, Oceanic, Native American, Celtic, Byzantine, Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque, Rococo, Neoclassicism, Arts and Crafts, Art Nouveau, Art Deco, Modernism and Post-Modernism (the eclectic combination of any of the aforementioned).

The 'Illuminated Ornamental Cross' from the Lindisfarne Gospels unites both symbolic and decorative shapes in one design. The symbolic shape of the cross forms the framework for the elaborate network of Celtic decoration. Within its complex ornamentation lies another layer of symbolism: the endless interlacing of knots and spirals, a visual metaphor for our universal coexistence with God, nature and one another.

Transparent, Reflective and Opaque Shapes

RICHARD ESTES (b. 1932)

Donohue's, 1967 (oil on masonite)

Transparent shapes allow light to pass through so that you are able to see what lies beyond them.

Reflective shapes reflect light to create a mirror image of what is reflected on their surface.

Opaque shapes absorb light but also reflect some of it as color. As light is not able to pass through them, you are unable to see through them.

Richard Estes paintings are a perfectly judged balance between the transparent, reflective and opaque forms of the metropolitan environment of New York. In his painting of 'Donohoe's', the image is essentially a view into a diner through one of its windows. However, plate glass windows are not only transparent, they also have reflective properties. Consequently, the view of the window becomes a composite of the inside of the diner and a reflection of the street outside.

Apart from the obvious virtuosity of his painting technique, Estes demonstrates remarkable drawing and compositional skills in the way he edits and balances the shapes and forms that we see through the window (the table, radiator, figures and strip light) with the reflections on the surface of the window (the buildings, pedestrians, traffic lights, signage, smoke and clouds). His paintings always seem to trigger a compulsive curiosity, pulling the viewer into the complexity of their details. For example, note how 'Donohue's' is not actually the name of the diner; it is, in fact, the restaurant across the street whose name is reflected in the window. The visual poetry of this interior-exterior dialogue is both the fascination and hallmark of Estes' paintings.

The Perspective of Shapes

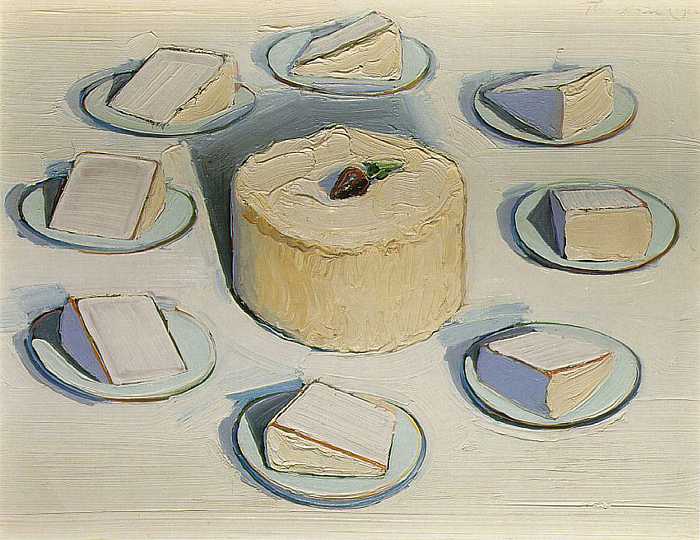

WAYNE THIEBAUD (1920-)

Around the Cake, 1962 (oil on canvas)

Perspective drawing is the technique that artists use to calculate the angles of a three dimensional shape when drawing it on a two dimensional surface.

Wayne Thiebaud's painting 'Around the Cake' is a witty demonstration of perspective drawing. It illustrates two cakes: one in the center of the painting; the other cut into eight equal slices, each on its own identical plate and arranged in a circular order like the numbers on a clock. To evoke a sense of time and motion, each slice of the cake has been rotated by 45° as they advance around the clock. This painting has some of the contemporary irony that you expect to find in Pop Art but Thiebaud's slow sumptuous painting technique draws on the unexpected influences of artists like Giorgio Morandi and Chardin and the art historical lineage that they represent.