Paintings by Vincent Van Gogh

An exploration of Van Gogh's early paintings in Holland and how his ideas and techniques developed in Paris, Arles, Saint-Rémy, and Auvers-sur-Oise.

VINCENT VAN GOGH (1853-1890)

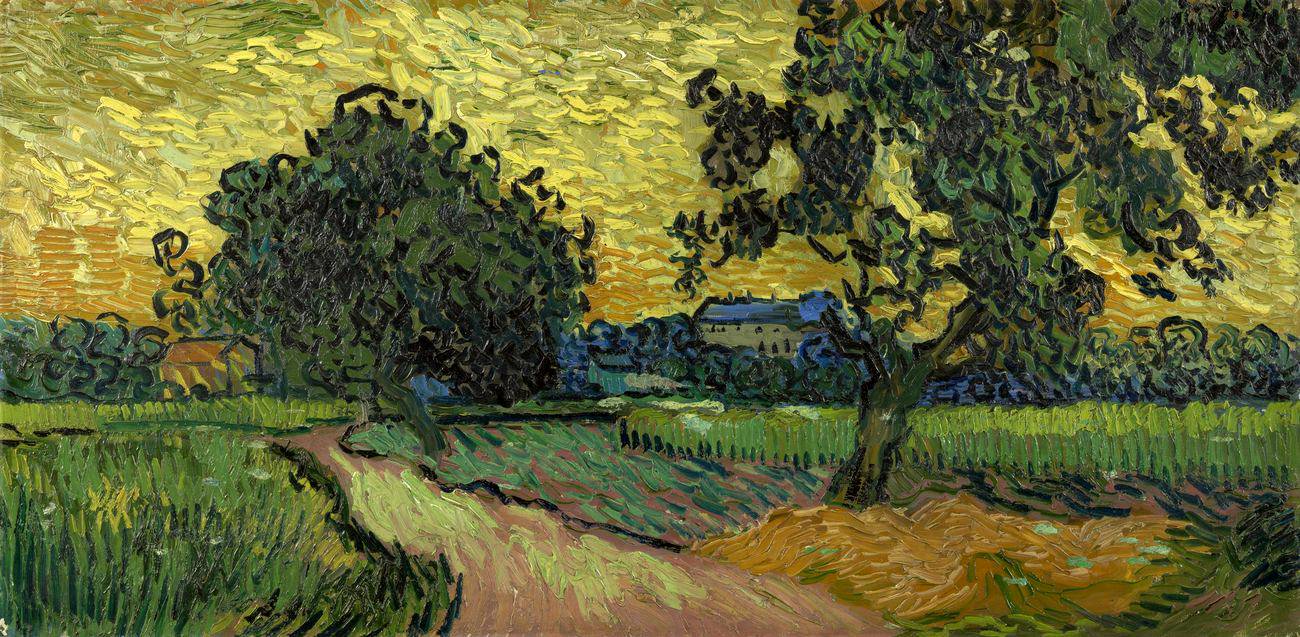

'Chateau in Auvers at Sunset', 1890

(oil on canvas)

Vincent Van Gogh is one of the most popular artists of all time. His radical paintings are characterized by what he called his ‘terrible clarity of mind’, an elevated level of perception that raised his creative energy to euphoric heights. In a letter to his brother Theo he wrote, "I have a terrible clarity of mind at times, when nature is so lovely these days, and then I’m no longer aware of myself and the painting comes to me as if in a dream. I am indeed somewhat fearful that that will have its reaction in melancholy when the bad season comes....." His melancholic counterpart to this visionary state was a disorder, believed to be temporal lobe epilepsy. This affliction caused him to experience extreme mood swings which marred all his personal relationships. Although this illness was responsible for periods of depression, he also had intervals of exhilaration when he painted with an instinctive understanding of the emotive nature of color, and how to use it at its highest pitch. The raw energy of his vigorous brushwork and his passionate use of vibrant color touch the heart of his public, who feel that he selflessly compromised his presence of mind to engage with his subjects on such an intense level. In effect, he provides the emotional safety net that allows us to experience his extraordinary view from the edge from a secure standpoint.

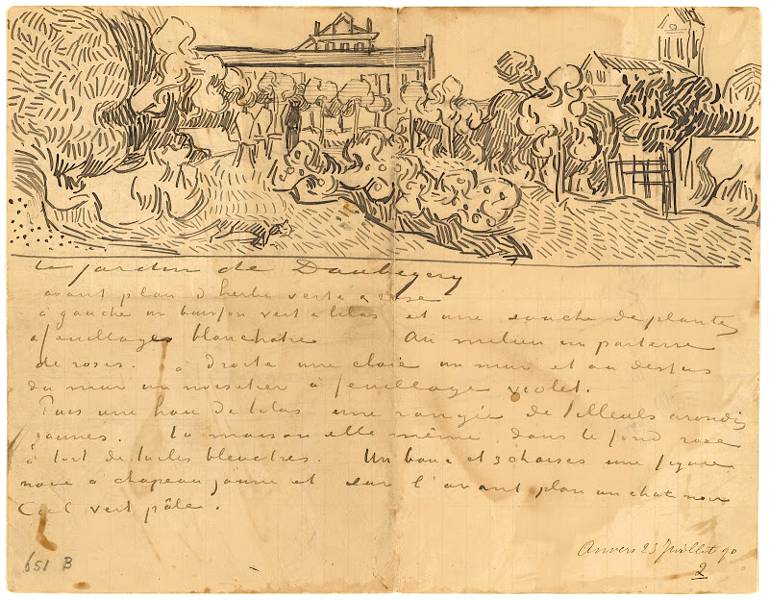

An historic misunderstanding of his illness has given rise to his ill-considered reputation as the crazy Dutchman who painted in an uncontrollable frenzy and cut off his earlobe in a fit of despair. However, this tabloid caricature is far from the truth. Van Gogh did endure dark days of depression, but he was too ill to work when his disorder took hold. In the intervening periods when he was well, he painted with a remarkable clarity of thought that is revealed in over 650 letters to his brother Theo, many of which explain the rationale behind his artistic choices and some of which he illustrated to explain his ideas. Very few artists have left such an honest, coherent and unpretentious analysis of their artwork that endorses the passion, perception, and integrity of their output.

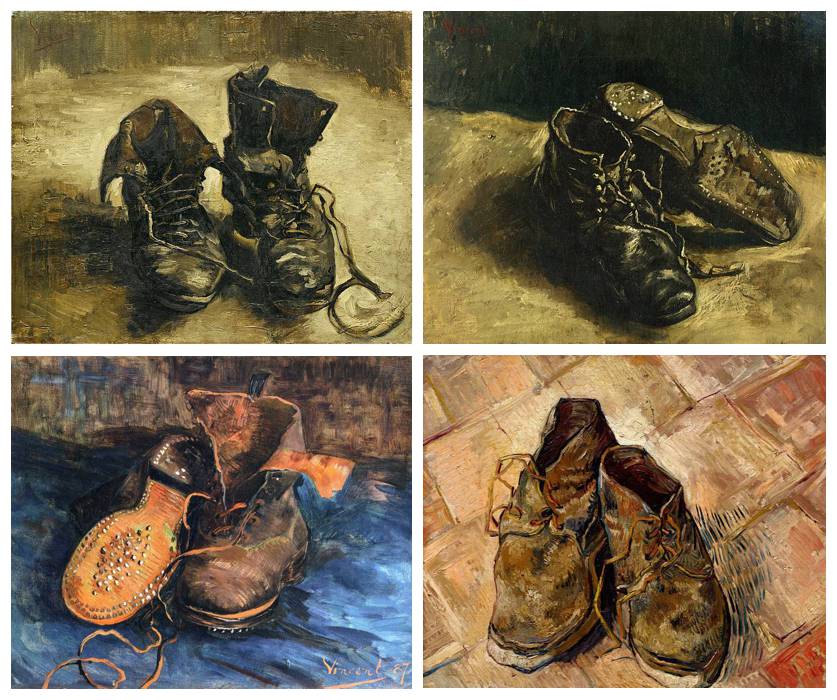

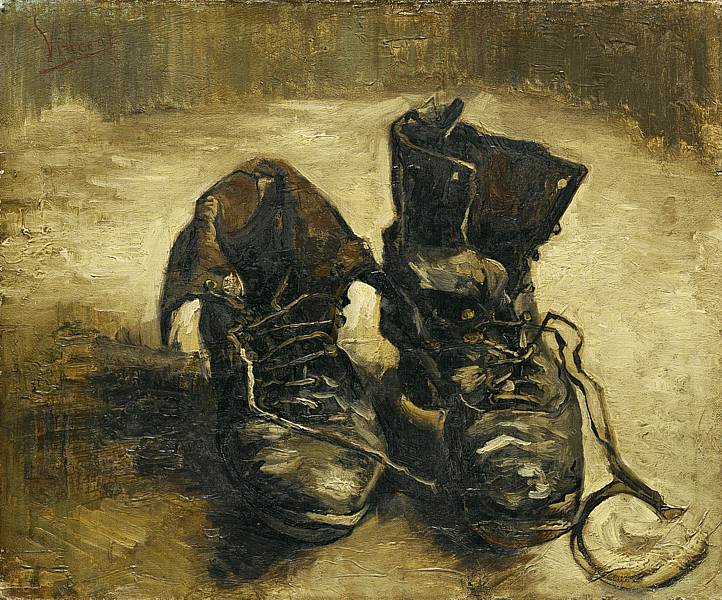

VINCENT VAN GOGH (1853-1890)

'Shoes', September-November 1886 (oil on canvas)

Van Gogh was born in Groot Zundert, Holland in 1853 to Theodorus Van Gogh, a protestant minister, and his wife Anna, a keen watercolourist who encouraged her son's interest in art. As a child he was a loner with a difficult nature who grew into a troublesome adolescent with no clear direction in life. His father's brother, Uncle Cent (short for Vincent) who was a successful art dealer, found him a job as a clerk at Goupil & Co., the international art dealership in the Hague. At first Van Gogh worked hard in the post, but after a few years he lost interest in the type of paintings he was handling. As a result, his performance deteriorated eventually leading to his dismissal. His next step was to follow in his father's footsteps and train for the ministry, but this proved to be another dead-end as he could not cope with the rigorous studies involved. Determined not to be defeated, he took up a position as a lay preacher in the Borinage, an impoverished coal mining region in Belgium. He threw himself into the work with excessive zeal, giving up his comfortable lodgings to a homeless man, and distributing his clothes among the poor. His excessive self-denial and overzealous approach to the work undermined his ability to support his congregation and gradually led to a deterioration of his physical and mental health. When the church authorities witnessed his destitute condition, they were embarrassed by his behaviour and dismissed him. After living rough for a few months with nowhere to stay, he returned to his family home to recuperate. Following a period of convalescence and frustration at his inability to work under any authority, he finally resolved to devote himself to his art, an interest that had engaged him since childhood. The year was 1880 and he was 27 years old.

His Dutch Roots (1880-1886)

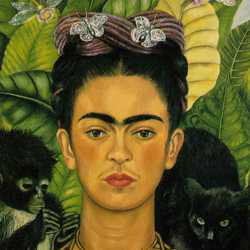

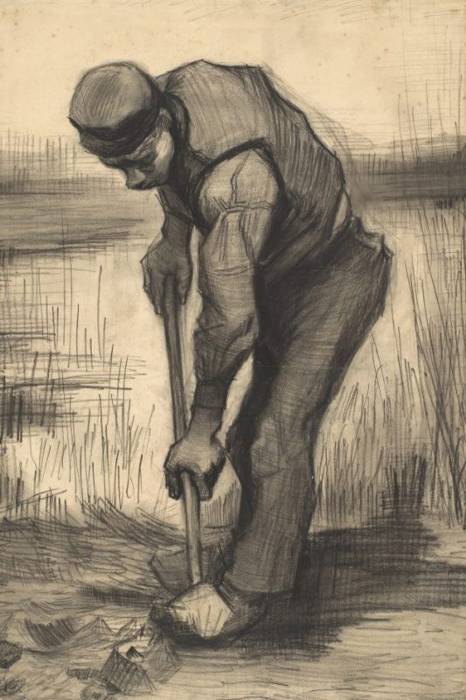

VINCENT VAN GOGH (1853-1890)

'Digger', Summer 1885 (chalk on paper)

Van Gogh threw himself into his artwork with the same obsessive zeal he displayed as an evangelist. At last, he had found his natural calling and felt a deep sense of fulfilment as his work improved. However, this contentment was short-lived as his unpredictable outbursts resurfaced, probably linked to his obsessional pace of work. As a result, his family and personal relationships faltered, and on Christmas Day 1881 he stormed out of the house after a furious argument with his father about religion. Once again, he found himself homeless but, with the financial and emotional support of his brother Theo, whom he would come to depend on for the rest of his life, he moved to the Hague to pursue his development as an artist.

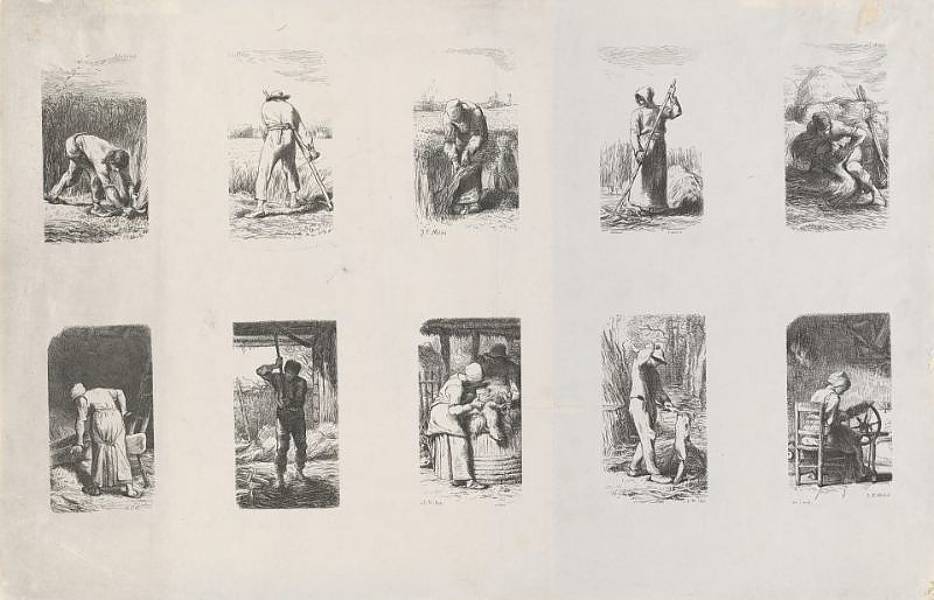

Van Gogh’s early paintings adopted the dark earthy palette of traditional Dutch art, but with a hint of modernity in the choice of his subject matter. He had long admired the contemporary Realist paintings of the great French artist Jean-François Millet (1814-1875), who depicted the life of peasant workers with a deep sympathy for the inequalities and hardships they endured. Millet's recognition of social injustice was something that Van Gogh identified with after his time among the poor of the Borinage. In a letter to Theo from 1879 he described the desperate conditions he witnessed there, "Its a sombre place, and at first sight everything around it has something dismal and deathly about it. The workers there are usually people, emaciated and pale owing to fever, who look exhausted and haggard, weather-beaten and prematurely old, the women generally sallow and withered. All around the mine are poor miners’ dwellings with a couple of dead trees, completely black from the smoke, and thorn-hedges, dung-heaps and rubbish dumps, mountains of unusable coal." With his first-hand appreciation of the deprivations they suffered, Van Gogh embraced the humble existence of miners and farm workers as the subject of his early work, demonstrating his respect for the dignity of their labour.

During this period, Van Gogh focused mainly on developing his drawing skills, practicing techniques from 'The Bargue-Gérôme Drawing Course', a 'teach yourself how to draw course' that is still in print today. In a letter to Theo he wrote, "I’ll tell you, then, that I’ve sketched the 10 sheets of Millet’s Labours of the Fields (in approximately the dimensions of a sheet of the Bargue Cours de dessin) and that I’ve completely finished one of them, namely The Woodcutter." In September 1889, Van Gogh produced a series of small paintings, including ‘The Woodcutter’ based on these prints.

Van Gogh also took painting lessons from his cousin-in-law, Anton Mauve, a Dutch realist artist who was a leading member of the Hague School. Although he was heavily influenced by both the style and content of Mauve's work, his lessons were terminated as Mauve could not tolerate his unconventional character, declaring that he was impossible to teach.

By virtue of his emotional instability, the Van Gogh we all know evolved as an uncompromising self-taught artist, which is one of the things that people love about him. You don’t need any special knowledge or have to understand its historical context to appreciate his art. You instinctively experience and empathize with it on a visceral level due to its profound honesty and poignant humanity.

VINCENT VAN GOGH (1853-1890)

'The Potato Eaters', 1885

(oil on canvas)

After leaving the Hague, Van Gogh spent the autumn of 1883 painting the sparse landscapes of Drenthe in northern Holland, before returning to his family's new home in Nuenen in the south of Holland. His father, who had been reassigned to the church there, welcomed him back like the prodigal son. Nuenen was a rural town of farmers, weavers, and peasant labourers; a congregation of humble workers that were ideally suited to Van Gogh's preferred subject matter. It was here in 1885 that he painted his first major work, 'The Potato Eaters'.

Van Gogh saw 'The Potato Eaters' as his crowning achievement to date; a demonstration of all that he had learned in the previous five years. The numerous preparatory studies he produced for the final version are a testament to his determination to make a significant statement through this work. With its flawed draughtsmanship and mournful color, he was aware of its technical deficiencies from an academic viewpoint. However, he instinctively knew that he created something that sincerely expressed his deepest feelings on the subject, a quality he believed could stand on its own and endure the test of time: "I know myself that there are flaws in it; all the same, precisely because I see that the heads I’m doing now are becoming more powerful, I dare assert that the potato eaters will also hold up in association with subsequent paintings." (Letter to Theo).

'The Potato Eaters' shows Van Gogh's sympathy for the hard life of the agricultural labourers. It portrays the modest meal of a Dutch peasant family as they sit down to eat at the end of a tiring day. The clock on the wall reads seven o'clock. A single oil lamp spotlights the haggard features of the four adult figures around the table. The child of the family is silhouetted with her back to the viewer, probably positioned there as her gentle features would have proved a problem given the coarseness of his painting technique.

Van Gogh creates a unity of colour and texture between the gnarled hands and faces of the peasants and the food and coffee they are sharing. His rugged earthy colours symbolise their closeness to and dependence on the land for their survival. In a letter to Theo he explains the ideas and techniques behind the work, ‘I had finished all the heads and even finished them with great care — but I quickly repainted them without mercy, and the colour they’re painted now is something like the colour of a really dusty potato, unpeeled of course. While I was doing it I thought again about what has so rightly been said of Millet’s peasants — ‘His peasants seem to have been painted with the soil they sow'.'

'The Potato Eaters' is the dark masterpiece of Van Gogh's Dutch period. Although it was initially criticised for its inept drawing and cumbersome technique, its raw emotional energy was the key that would, in due course, release art from the representational restraints of the 19th century academies and open the door to the expressive freedoms of Fauvism and Expressionism in the 20th century.

Following the death of his father in 1885, Van Gogh moved out of the family home and rented a small room above an art gallery in Antwerp. At first things were looking up and he attended classes at the Academy of Fine Arts to advance his drawing skills. However, once again his emotional vulnerability resurfaced, and he spiralled into a state of ill health through self-neglect and overwork. His unstable behaviour, volatile opinions and rejection of the Academy's ideals led to conflicts with his tutors and his inevitable failure of the course. Unwilling to resit the year, he left the Academy and moved to Paris to live with Theo in Montmartre.

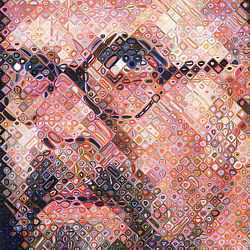

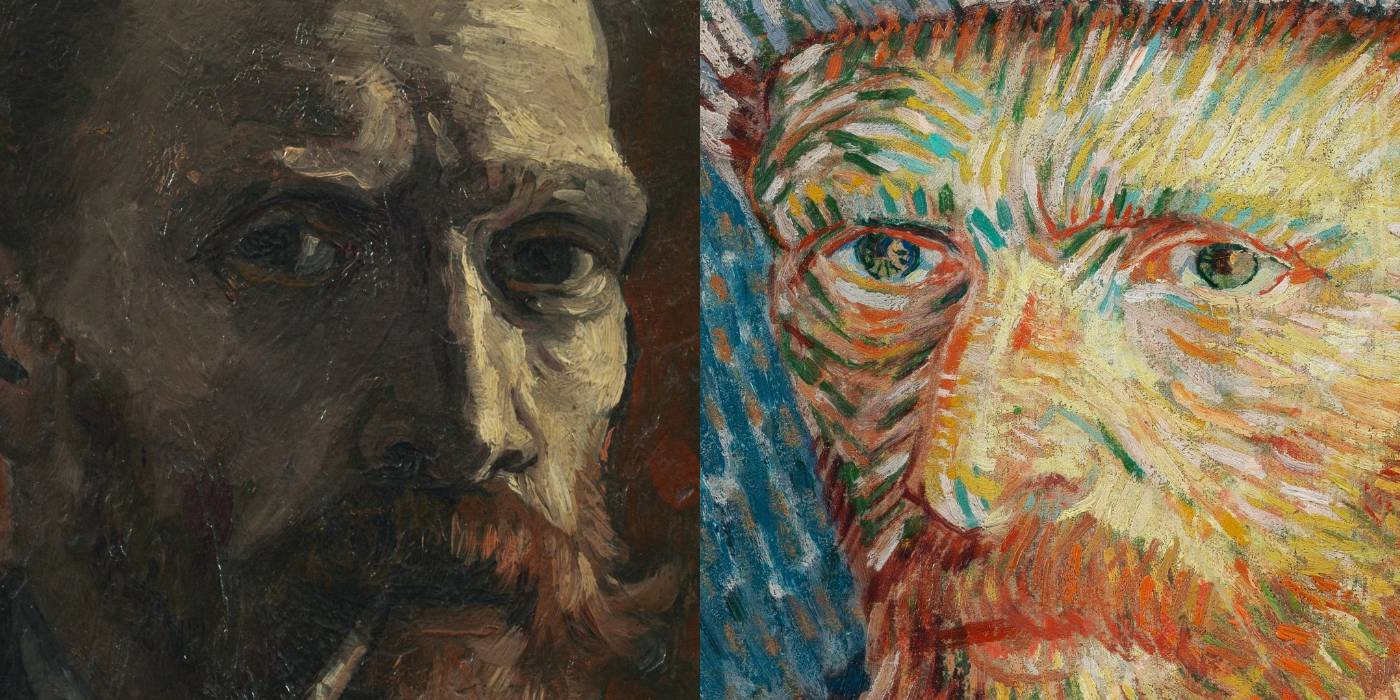

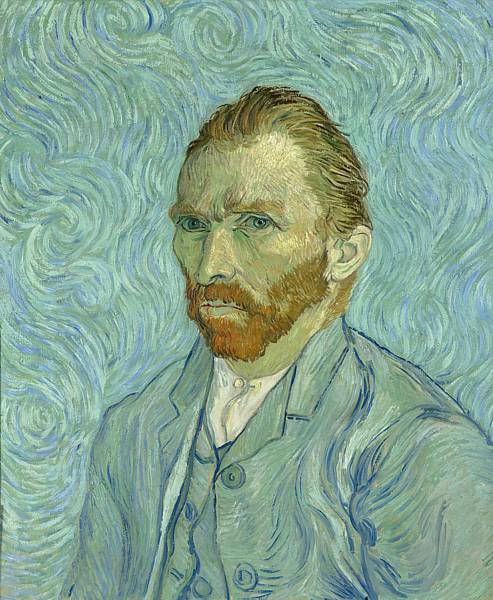

Paris transformed Van Gogh. When he encountered the vivid colors and spontaneous brushwork of the Impressionists, he discovered a new artistic language that opened his mind to the expressive possibilities of his art. Here was a group of artists whose radiant artworks eclipsed the cheerless hues of the Academic tradition. Theirs was a refreshing and vibrant approach to painting that mirrored his own passionate outlook. You can see the dramatic effect of their influence on Van Gogh's style in the details of his two self-portraits above, one painted a few months after he arrived in Paris, the other a year later.

VINCENT VAN GOGH (1853-1890)

'Self Portrait with Pipe', September-November 1886

(oil on canvas)

Van Gogh's 'Self Portrait with Pipe' was painted six months after he moved to Paris in 1886 and is still typical of his earlier paintings. The dark earthy tones, characteristic of traditional Dutch art, are used to create an image of humble dignity. This work is influenced by the art of his former tutor, Anton Mauve. The style of the image, particularly the beard and hair, bear a strong resemblance to a Mauve himself. It is peculiar how Van Gogh ages himself dramatically in one of his earliest self-portraits in trying to emulate the status of older artist. The one feature that distinguishes his work from conventional Dutch art is the unrefined expression of his brushwork, a quality that he would adapt as he absorbed the influence of Impressionism.

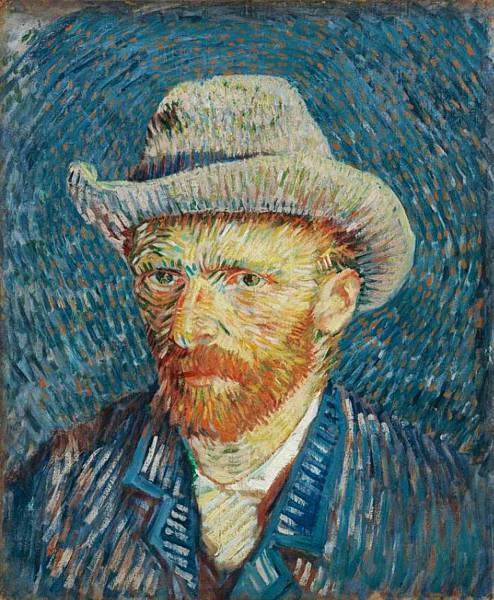

VINCENT VAN GOGH (1853-1890)

'Self Portrait with Grey Felt Hat', September-October 1887 (oil on canvas)

His 'Self Portrait with Grey Felt Hat' was painted a year later and shows a radical change in style. When Van Gogh first arrived in Paris, he was impressed by the Pointillist techniques of Georges Seurat who painted in tiny dots of unmixed colors which fuse optically into subtle hues as the spectator steps back to take in the image. However, without Seurat's delicate analytical approach to the technique, Van Gogh's attempts at pointillism were generally more robust, but they do start to reveal the main element of his true genius - an instinct for the expressive power of color. Many of Van Gogh’s early portraits are experiments in adapting Impressionist and Pointillist techniques by modifying their analytical use of vibrant colors to suit his more emotional approach to painting.

In this work we have a perfect balance between the vitality of Van Gogh's color and the energy of his brushwork. His confidence and control of color is developing. The tones of the face form a traditional portrait, but the colors used to create them explode like a multicoloured firework. He harnesses the expressive energy of his brushstrokes by controlling their rhythm, size, and direction as they radiate outwards from his eyes to build up the blue and orange aura that frames his head.

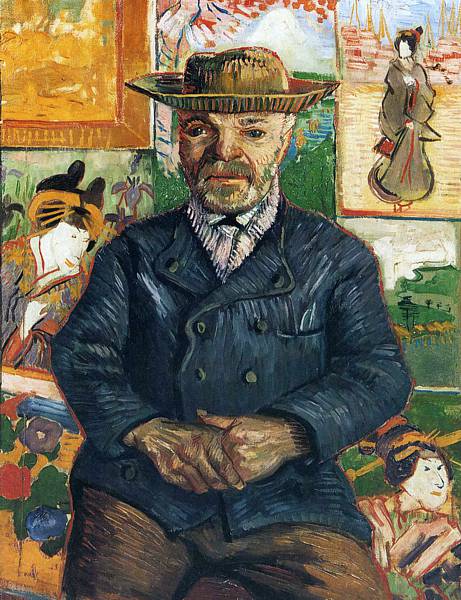

VINCENT VAN GOGH (1853-1890)

'Père Tanguy', 1887

(oil on canvas)

Julien Tanguy ran an art supply shop that also functioned as a small gallery in the Montmartre district of Paris. He was an enthusiastic supporter of the Impressionists, often supplying them with art materials in return for their paintings which he sold in his shop. Affectionally nicknamed Père (father), due to his kindly nature, he was one of the first dealers to exhibit Van Gogh's paintings.

This painting of 'Père Tanguy', is the second, and best of three portraits of the dealer painted by Van Gogh. It reveals another development in his style with the introduction of Japanese woodblock prints as a background to the work. Prints by Ukio-e artists such as Hokusai and Hiroshige were admired by many of the Impressionists and Van Gogh had a vast collection of these that he used to decorate his studio. In a letter to Theo, he mentions that 'My studio’s quite tolerable, mainly because I’ve pinned a set of Japanese prints on the walls that I find very diverting.' Their bold use of flat color and firmly outlined forms became a significant feature in Van Gogh's art, a characteristic that would evolve as his work matured. You can see the first signs of this in the way he outlines the figure of Tanguy in red, linking it to similar details in the prints.

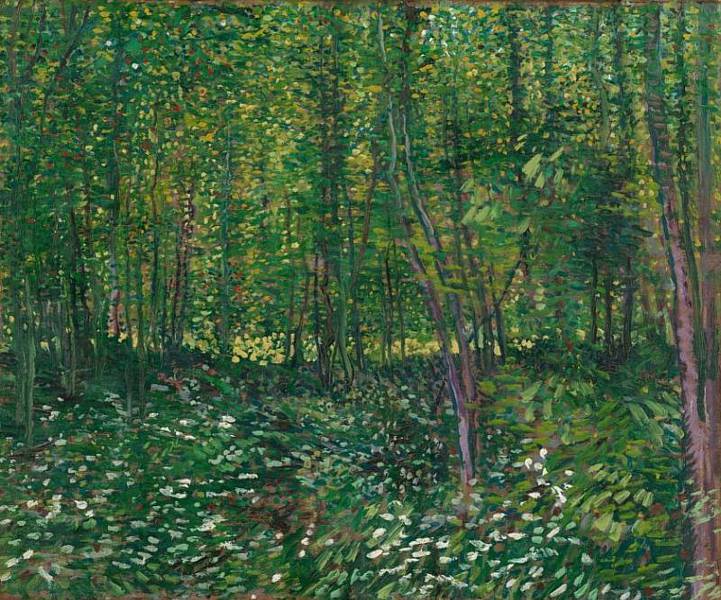

VINCENT VAN GOGH (1853-1890)

'Trees and Undergrowth', 1887

(oil on canvas)

Another aspect of French Impressionism that Van Gogh embraced was painting outdoors. Traditionally artists would sketch a landscape on the spot and use the study as a reference when finishing the work in the studio. The Impressionists did not draw a distinction between a sketch and a finished painting as they needed to work quickly to capture the vibrant qualities of light and color before they changed. As a consequence, their images sacrificed some detail but gained an expressive vitality that was impossible to achieve through a more refined technique. Their spontaneous method perfectly complemented Van Gogh's impulsive approach to painting and changed the course of his art.

In 'Trees and Undergrowth', Van Gogh immersed himself in the depth of the forest where the atmosphere is dappled with a spectrum of green and yellow tones. You cannot see the sky through the lush foliage, only the effects of its light in the green glow of the undergrowth. The entire surface of the painting is stippled in a myriad of Pointillist brushstrokes which progressively darken to suggest the illusion of depth as they recede into the woods . Your eye is gradually drawn into the work by the dabs of white wildflowers in the foreground. In the centre of the painting a horizontal band of yellow dots suggest a sunlit clearing beyond the trees, whose vertical trunks lead the eye into it like the receding transversals in a perspective drawing.

VINCENT VAN GOGH (1853-1890)

'The Yellow House', 1888

(oil on canvas)

Although the Parisian art scene provided the stimulus that Van Gogh needed to boost his creativity, his challenging personality alienated many of the artists and dealers that he met there. He was a social misfit in the cultured 'café society' that the Impressionists enjoyed, and he needed to relocate to a more agreeable environment. In a letter to his little sister Willemien he wrote, 'I believe that I’ll make more progress and that things will run their course. It’s my plan to go to the south for a while, as soon as I can, where there’s even more colour and even more sun'.

Van Gogh imagined 'the south' with its clear blue skies, rich green cypresses, golden fields and red earth to be the French equivalent of the images he loved from his collection of Japanese prints. So, on 20th February 1888, he set off for the town of Arles in the south of France with the romantic notion of establishing an artists' colony where all would work together in the Provençal sunshine, a perfect antidote to the Parisian gloom.

The first artist he invited to join him was Paul Gauguin, who initially refused but finally agreed when Theo offered to pay his fare. Van Gogh was bursting with expectation and ideas for Gauguin's arrival. He prepared one of the rooms he rented in 'The Yellow House' as a communal studio and decorated it with paintings of 'Sunflowers', an optimistic symbol of the life he envisaged in the days ahead. He explained in a letter to his brother, ''I’m painting with the gusto of a Marseillais eating bouillabaisse, which won’t surprise you when it’s a question of painting large Sunflowers. I have 3 canvases on the go, 1) Three large flowers in a green vase, light background.... 2) Three flowers, one flower that’s gone to seed and lost its petals and a bud on a royal blue background.... 3) Twelve flowers and buds in a yellow vase.... 4) So the last one is light on light, and will be the best, I hope. I’ll probably not stop there. In the hope of living in a studio of our own with Gauguin, I’d like to do a decoration for the studio. Nothing but large Sunflowers." He eventually ended up painting seven versions of 'Sunflowers', one of which has since been lost.

VINCENT VAN GOGH (1853-1890)

'Sunflowers', 1888

(oil on canvas)

This version of 'Sunflowers', which is now in the National Gallery in London, has been called 'the most popular still life in the history of art'. Although Van Gogh said he painted it with 'three chrome yellows, yellow ochre and Veronese green and nothing else', he also uses crimson for the seeds, and blue for his 'Vincent' signature and the lines that divide the vase and separate the foreground and background. However, this unpretentious painting is a genuinely radical concept. It is both modern, inspired by his love for the flat graphic images of Japanese prints and their symbolic use of color, and traditional as it references the genre of Dutch Vanitas still lifes from his own heritage in the dead seed heads that have lost their petals.

'Sunflowers' is a remarkably simple composition with fifteen flowers arranged symmetrically in vase, but the painting needs this simplicity to display the expressive power of its elements: color, texture, and shape. One of the first things you notice is that there are no shadows to mould the shapes of the vase and flowers or to tie them to the foreground. Color and texture are used to render the shapes of the objects, and each plays its part in the dynamics of the work.

-

Color: Color is the main element of the work which is painted almost entirely in yellow hues. Yellow is used to generate the vitality of the sunflowers rather than describe their form. This color had a profound meaning for Van Gogh who uses it like no other artist to embody his feelings of elation and the energy of nature. If you see this painting hanging in the National Gallery with its heavy brown frame against a dark wall, it is so radiant that it looks like a backlit image. It seems to have no need of tone and appears to generate its own energy.

-

Texture: The texture of the paint and the structure of his brush strokes add depth to the painting and transmit the intensity of Van Gogh's response. In both his drawings and paintings, Van Gogh had devised an economic vocabulary of marks that manage to strike a balance between the naturalism and stylistic expression of the subject. The seed heads are stippled; the leaves and petals are heavily stroked with some added detail scratched in using the end of his brush; the background is a thick impasto of cross-hatched brushstrokes that enhance the presence and punch of its chrome yellow ground; and the stalks are a simple flat green. The only real concession to light and shade is a dollop of white to represent a reflection on the top half of the vase. The actual physicality of the paint throughout the work adds so much substance to the image that it makes any need for tonal modelling redundant.

-

Shape: The basic composition of the painting is created using a counterpoint of yellows, with the dark flowers silhouetted against a light background, while the light half of their vase is contrasted with the darker foreground. The interplay of the positive shapes of the flowers with the negative space of their illuminated background generates a dynamic interaction that adds to the life of the work. The two-fold shapes of the sunflowers are a mixture of the soft round forms of the seed heads and the sharp jagged petals of the flowers, a disparity that seems reflect the discord in Van Gogh's own personality. Like many great paintings, the work often tells you as much about the artist as it does about the subject. When you put so much of yourself into an artwork, it is only natural that you will expose elements of your own character.

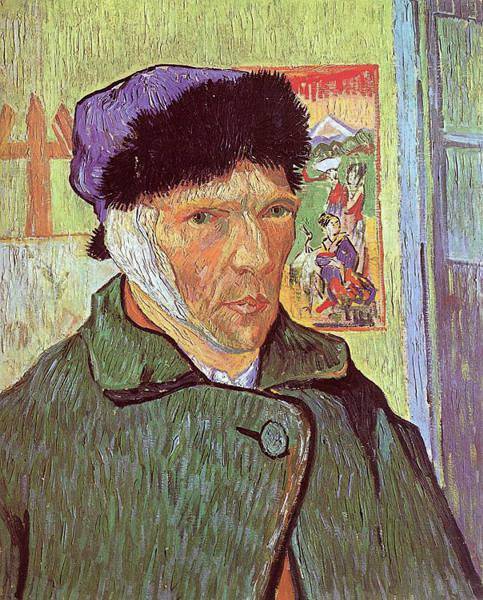

VINCENT VAN GOGH (1853-1890)

'Self Portrait with Bandaged Ear', 1889

(oil on canvas)

Van Gogh's hopes for his Arlesian brotherhood of artists were crushed by Gauguin before they ever had a chance to develop. From the outset he was a reluctant participant who was sceptical of Van Gogh's vision for a creative haven in Arles. The two artists were essentially incompatible personalities whose partnership was doomed to failure. Van Gogh was an idealist whose identity lay in the heightened emotions of his art, while Gauguin had a more cynical nature that was quick to criticise. After some initial civility on both their parts they began to argue, with Gauguin growing in frustration at Van Gogh's pipe dreams. At first, despite their contradictory opinions, Van Gogh was in denial that their relationship was disintegrating. He put down Gauguin's exasperation as a quirk of his bohemian nature, but as their arguments escalated and the tension grew, his mental state deteriorated until one night he threw a glass of absinthe at Gauguin and threatened him with a razor. In fear for his safety, Gauguin packed his bags and took refuge in a local hotel.

On realising that his delirious behaviour had put an end to his dream of an artistic community in Arles, Van Gogh suffered a complete breakdown. In this deranged state he cut off part of his left ear, wrapped it in newspaper and, according to a contemporary account, handed it to a girl outside the brothel where she worked as a cleaner with the instruction to “guard this object carefully.”

When Gauguin returned to the 'Yellow House' the following day, he was surprised to find the police controlling a crowd outside the property. However, on entering he was horrified to see the blood-smeared walls and furniture with Van Gogh lying comatose on his blood-stained bed. Once it was established that Van Gogh was still alive, the police took him to the hospital in Arles, and Gauguin departed for Paris never to return. Van Gogh was discharged after two weeks but relapsed due to anxiety and overwork and was subsequently readmitted. When he eventually improved enough to return to the 'Yellow House' he was hounded by some members of the community who formed a petition to have him removed from the town.

One of the main artistic differences between Gauguin and Van Gogh was that Gauguin combined both observation and imagination in his paintings. He encouraged Van Gogh to adopt a similar approach, but he could not adapt his style. In a letter to his friend, the artist Emile Bernard, he explains, ‘….I can’t work without a model. I’m not saying that I don’t flatly turn my back on reality to turn a study into a painting — by arranging the colour, by enlarging, by simplifying — but I have such a fear of separating myself from what’s possible and what’s right as far as form is concerned.’

Van Gogh needed a subject in front of him to respond to, and it is the simplicity and sincerity of this response that raises Van Gogh's art to the highest level. When you look at one of his paintings everything is honest and direct: the drawing seems elementary, the painting technique looks uncomplicated, and the subject is unpretentious. You are almost fooled into thinking 'I could do that' until you try. Although the individual elements of the work may appear to be unrefined, they take on an inexplicable quality when filtered through Van Gogh's extraordinary vision. His paintings have that rare appeal that speaks to children, their parents, and their grandparents, generation after generation, irrespective of their knowledge and understanding of art. They are transcendent and timeless.

You can see the honesty of his response in 'Self Portrait with Bandaged Ear'. It tells the story of his time in Arles in three simple images. The artist's easel places him in his studio, the Japanese print represents his hopes for his Arlesian community of artists, and the frankness of the way he portrays himself acknowledges what he has lost in pursuit of his idealistic dreams. Paradoxically, even though the subject addresses Van Gogh's physical and psychological distress, the vitality of his expressive technique and exhilarating color leave you with a surprising sense of hope, a triumph of his spirit in the face of his adversity.

VINCENT VAN GOGH (1853-1890)

'Fountain in the Garden of the St.Paul Asylum', 1889

(brown chalk and ink on paper)

With nothing left to keep him in Arles and growing more worried about his illness, Van Gogh moved to the nearby town of Saint-Rémy and voluntarily checked into the asylum of Saint Paul de Mausole. The admissions register records a report from the doctor in Arles hospital who states that Van Gogh ‘suffered an attack of acute mania with generalised delirium. At that time he cut off his ear. At present his condition has greatly improved, but he nevertheless thinks it helpful to be cared for in a mental asylum’. After being examined on entry to the asylum, their physician reported, ‘I consider that Mr Van Gogh is subject to attacks of epilepsy, separated by long intervals, and that it is advisable to place him under long-term observation in the institution.’

Van Gogh spent a year in their care, but his mental health gradually declined over the period. His condition was not fully understood by contemporary medicine and the treatment he received was no more than the cold bath therapy that athletes use today to treat sore muscles. He experienced convulsions and episodes of depression every few months but, in his intervening periods of lucidity, he produced around 130 paintings. Ironically, as his condition deteriorated his creativity intensified. In a letter to Theo he wrote, ‘As far as I can judge I’m not mad, strictly speaking. You’ll see that the canvases I’ve done in the intervals are calm and not inferior to others.’ The works he produced in Saint-Rémy, notably his paintings of 'Irises' and 'Starry Night', are among his very best.

At first Van Gogh was confined within the walls of the asylum and focused on painting the ivy laden trees and flowers in the garden. The institutional routine gave him a more stable lifestyle which seemed to strengthen his artistic sensibilities. In his ink drawing of the 'Fountain in the Garden of St.Paul's Asylum' we can see that the stylistic vocabulary of his mark making (dashes, strokes, stipples and hatching) has become consistent for both his drawings and paintings. Unlike his earlier work where his drawings were either formative lessons or exploratory studies for his paintings, the two disciplines now flow as one creative stream, each capable of holding their own as an expressive medium.

VINCENT VAN GOGH (1853-1890)

'Irises', 1889

(oil on canvas)

Van Gogh started to paint the irises in the asylum garden within the first week of his stay. He was sufficiently inspired by their natural beauty to produce four different studies: two still lifes with irises in a vase, an isolated plant in the garden, and a close-up view of the flower beds. In the latter study, which we have illustrated, his use of color is intense, ablaze with contrasts. The purple irises (the red in their pigment has faded leaving them blue) harmonise with their emerald leaves and stems, but conflict with their yellow-green background that fills the negative space between the flower heads. Similar vibrant contrasts occur between the green bush and its orange flowers in the background, and the emerald leaves and their reddish-brown soil in the foreground. The effect of these contrasts is to amplify the intensity of color throughout the picture.

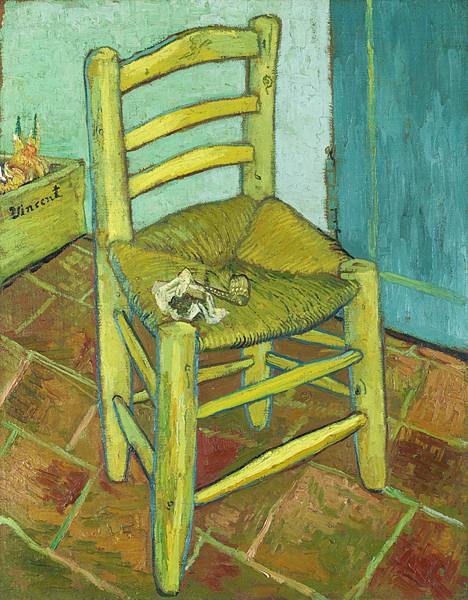

The style of the painting shows the ongoing influence of Japanese prints in its flatly painted flower heads and leaves, outlined with dark contours to emphasise their organic shapes, rich colors, and rhythmic patterns. Even the composition has a Japanese feel about it with its close-up, cropped arrangement that unconventionally reads from right to left. A single white iris interrupts the swaying movement of the flowers, possibly a visual metaphor for his seclusion. He used this type of symbolism in earlier paintings such as his series of 'Shoes' (1886-88), 'Van Gogh's Chair with Pipe' and 'Gauguin's Chair' (1888), where he employed still life objects as coded portraits of himself and Gauguin.

In September of 1889, Theo submitted 'Irises' to the Salon des Independants exhibition, but it never sold. However, on 11th November 1987, it was sold at Sotheby's New York for a staggering $54,000.000, making it one of the most expensive paintings ever.

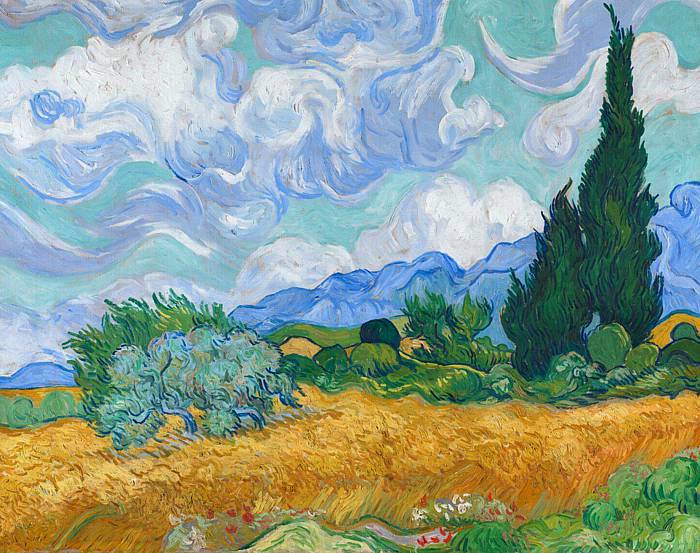

Cornfield and Cypresses (1889)

VINCENT VAN GOGH (1853-1890)

Image 1: 'Cornfield with Cypresses', 1889

(oil on canvas)

National Gallery, London

Image 2: 'Cornfield with Cypresses', 1889

(oil on canvas)

Private Collection, Switzerland

About a month after he was admitted to Saint Paul's, Van Gogh was allowed to paint outside the walls of the asylum. Ever since he arrived in Provence, he had been captivated by the local cypress trees, the dark green conifers that are often associated with mourning due to their familiar presence in cemeteries. In a letter to Theo he reveals, 'The cypresses still preoccupy me, I’d like to do something with them like the canvases of the sunflower because it astonishes me that no one has yet done them as I see them.'

This preoccupation takes form in several paintings of 'Cornfield and Cypresses'. Although his ideas were still based on first-hand observation, his brushwork was becoming more rhythmic, deliberately exaggerating the lyrical quality of his technique to express the energetic forces of nature he sensed in the landscape. He tries to explain this in a letter to Emile Bernard, 'But in the meantime I’m still living off the real world. I exaggerate, I sometimes make changes to the subject, but still I don’t invent the whole of the painting; on the contrary, I find it ready-made — but to be untangled — in the real world.'

To Illustrate this, we can examine two examples from the series:

Image A of 'Cornfield and Cypresses' was the earliest example of this subject and painted out-of-doors in July 1889. The fact that this 'Cornfield and Cypresses' painting was done in radiant sunshine where every detail catches the eye, naturally focuses Van Gogh's attention on the observation of the subject more than his stylistic considerations. Shortly after painting this he had a seizure which prevented him from working for several weeks.

Image B of 'Cornfield and Cypresses' is believed to be a studio reworking of Image A, painted in August during his convalescence from the attack. This was something that Van Gogh did with several paintings to refine his style and 'untangle' the essence of the work. In this version you can see a reduction of the detail, a more saturated and harmonic balance of color, and a greater flow to his brushwork. He was attempting to understand and emphasise those components of the painting that were key to its emotional exchange.

VINCENT VAN GOGH (1853-1890)

'Starry Night', 1889

(oil on canvas)

In his nocturnal landscape, 'Starry Night', Van Gogh finally achieved what Gauguin had encouraged him to create: a painting that relies on both observation and imagination. 'Starry Night' shares the same landscape as 'Cornfield and Cypresses' but with an additional development: an imaginary village with a traditional Dutch church in the middle of the Provençal countryside. This is an astonishingly intense work and a radical departure from his dependence on first-hand sources. He unites the celestial power of the stars with the primal forces of nature by linking the blaze of stellar energy to the flourish of cypresses and the rolling landscape. He achieves this by using the same flowing rhythm and size of brushstrokes for both close and distant elements, thereby flattening the perspective of the picture plane and consolidating its surface in a revolving vortex of color, pattern and texture. 'Starry Night' is not simply a landscape; it is a spiritual declaration of Van Gogh's faith in the power behind creation. The heavens and the earth are one in this wondrous universe.

VINCENT VAN GOGH (1853-1890)

'Self Portrait: Saint-Rémy', 1889

(oil on canvas)

Van Gogh's self-portrait from the Musée d'Orsay brings together all the elements of his later work: a choice of color that reflects his emotional state and a style of drawing that pulsates with energy. It was painted shortly after he left the St. Remy asylum in July 1889 and shows that he was still struggling with his state of mind. It is one of the most powerful self-portraits ever painted.

This work portrays Van Gogh's internal crisis: his piercing eyes hold you transfixed but their focus is not on what is happening outside, but inside his head. The energy of the picture builds from the eyes which are the most tightly drawn feature. The flow of his brushstrokes spread across the planes of his face, gaining energy as they ripple through his hair and jacket, finally bursting into the churning turbulence of the background. The pale blues and greens that he uses are normally calm colors, but when they are contrasted against his vivid red hair and beard, they strike a jarring note which perfectly sets the psychological tone of the portrait: the unflinching image of a man holding it together as he withstands his inner demons.

VINCENT VAN GOGH (1853-1890)

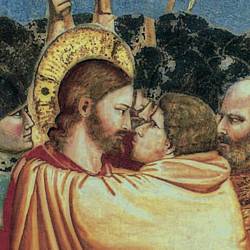

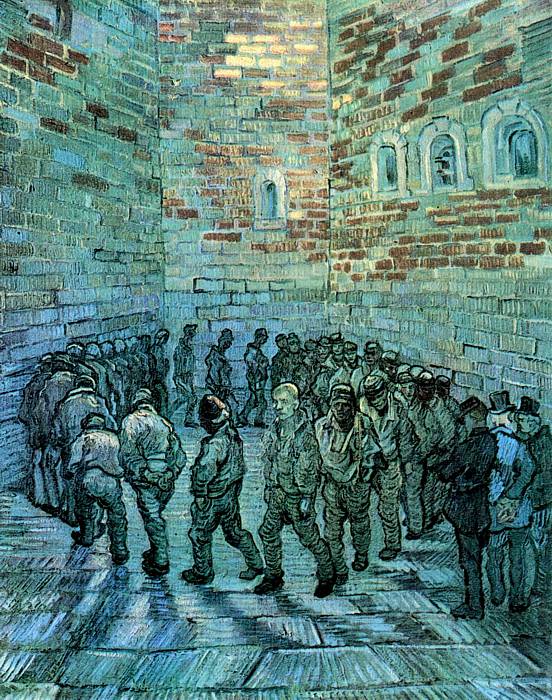

'Prisoners Round' (after Gustave Doré), 1890

(oil on canvas)

In the spring of 1890, Van Gogh's health was improving and Theo informed him that dealers were showing an interest in his work. The artist Camille Pissarro, a father figure to the Impressionists, suggested that a move back up north would be beneficial and arranged for him to continue his treatment in Auvers-sur-Oise under the care of Dr. Gachet, an eccentric physician and amateur artist.

Van Gogh was making significant progress in his art but after a trip to visit Theo in July, he realised that his brother was having financial problems. Theo was thinking of quitting his job at Goupil's and starting up his own business to lay a more solid foundation for his wife and new child. Van Gogh was concerned that Theo's increased responsibilities and reduced income would affect his ability to support him. He expressed these fears in a letter to his brother, 'Once back here I too still felt very saddened, and had continued to feel the storm that threatens you also weighing upon me. What can be done – you see I usually try to be quite good-humoured, but my life, too, is attacked at the very root, my step also is faltering. I feared – not completely – but a little nonetheless – that I was a danger to you, living at your expense....'. The distress he felt in becoming a burden to his brother, in addition to the threat of his relapsing illness, triggered a downward spiral in his mental stability that completely overwhelmed him. Despite Theo's attempts to convince him of his continued support, he could not shift his melancholic mindset and on 27th of July 1890 Van Gogh took his own life.

Several days after his death, Emile Bernard described the tragedy in a letter to the writer and poet Albert Aurier, 'On Sunday evening he went out into the countryside near Auvers, placed his easel against a haystack and went behind the chateau and fired a revolver shot at himself. Under the violence of the impact he fell, but he got up again, and fell three times more, before he got back to the inn where he was staying (Ravoux, place de la Mairie) without telling anyone about his injury. He finally died on Monday evening, still smoking his pipe which he refused to let go of, explaining that his suicide had been absolutely deliberate and that he had done it in complete lucidity. A typical detail that I was told about his wish to die was that when Dr. Gachet told him that he still hoped to save his life, he said, “Then I'll have to do it over again.” But, alas, it was no longer possible to save him....

....On the walls of the room where his body was laid out all his last canvases were hung making a sort of halo for him and the brilliance of the genius that radiated from them made this death even more painful for us artists who were there. The coffin was covered with a simple white cloth and surrounded with masses of flowers, the sunflowers that he loved so much, yellow dahlias, yellow flowers everywhere. It was, you will remember, his favourite colour, the symbol of the light that he dreamed of as being in people's hearts as well as in works of art....

....Many people arrived, mainly artists, among whom I recognized Lucien Pissarro and Lauzet, the others I did not know, also some local people who had known him a little, seen him once or twice and who liked him because he was so good-hearted, so human....

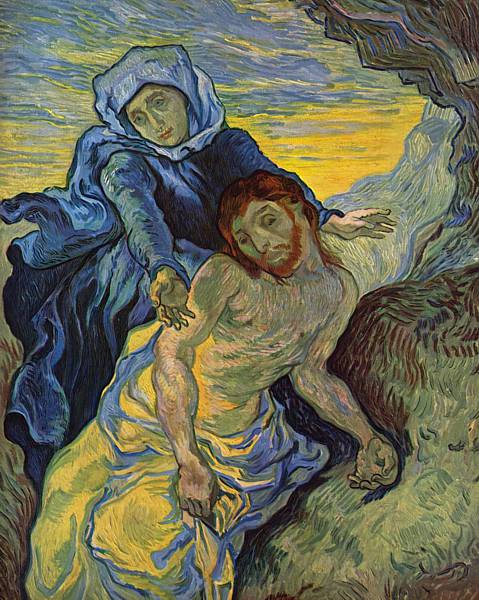

....There we were, completely silent all of us together around this coffin that held our friend. I looked at the studies; a very beautiful and sad one based on Delacroix's La vierge et Jesus. Convicts walking in a circle surrounded by high prison walls, a canvas (painted in the St. Paul's Asylum) inspired by Doré of a terrifying ferocity and which is also symbolic of his end. Wasn't life like that for him, a high prison like this with such high walls - so high…and these people walking endlessly round this pit, weren't they the poor artists, the poor damned souls walking past under the whip of Destiny?....

....But that is quite enough, my dear Aurier, quite enough, don't you think, about this sad day. You know how much I loved him and you can imagine how much I wept. You are his critic, so don't forget him but try and write a few words to tell everyone that his funeral was a crowning finale that was truly worthy of his great spirit and his great talent.

With my heartfelt wishes

Bernard.'

VINCENT VAN GOGH (1853-1890)

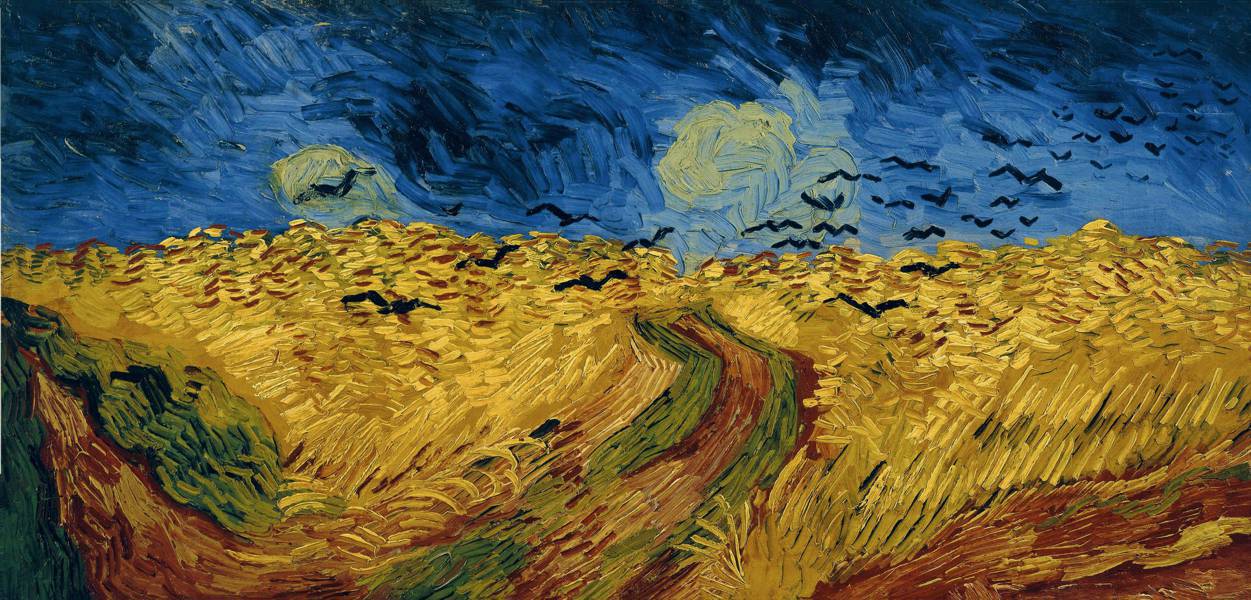

'Wheatfield and Crows', 1890

(oil on canvas)

Van Gogh's 'Wheatfield with Crows' is often considered to be his final work, but this is a common misunderstanding made by linking its ominous atmosphere to his tragic death. It is typical of his later work where the energy of his brushstrokes spontaneously echoes and amplifies the vital forces he experienced in looking at his subject. There is no preliminary drawing or planning involved, just a visceral response to what he sees and feels.

He describes the work in the same letter to Theo where he expressed his fears about becoming a burden to him, 'There – once back here I set to work again – the brush however almost falling from my hands and – knowing clearly what I wanted I’ve painted another three large canvases since then. They’re immense stretches of wheatfields under turbulent skies, and I made a point of trying to express sadness, extreme loneliness.'

One change he makes in these final works is in the dimensions of his canvas. In the last few weeks of his life he uses a double-square format (100cm x 50cm or 80cm x 40cm) to paint several panoramic views of Auvers-sur-Oise. In marked contrast to the foreboding mood of 'Wheatfield with Crows'', 'Chateau in Auvers at Sunset' (at the top of our page) is a more serene use of this format where he creates the gentle calm of a warm evening as the sun goes down. Gone are the black outlines of his Japanese influence which have fragmented and incorporated into the rhythms of his own brushwork. His palette is also limited to five or six colors. Van Gogh instinctively knew that the more he intensified his colors for their emotional impact, the more he had to restrict their number in order to avoid any chromatic dissonance. His succinct description of 'Chateau in Auvers at Sunset' reflects the unpretentious simplicity of his approach. 'Finally a night effect – two completely dark pear trees against yellowing sky with wheatfields, and in the violet background the castle encased in the dark greenery.'

The paintings of Van Gogh's final weeks embody each phase of his artistic growth in a passionate and dramatic style that introduces the principles of Fauvism and Expressionism fifteen years before they were defined.

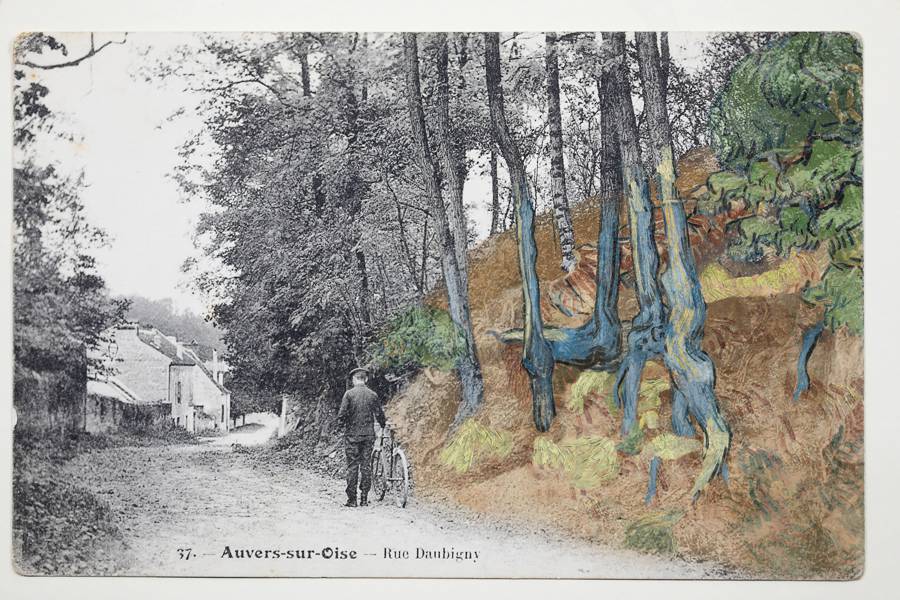

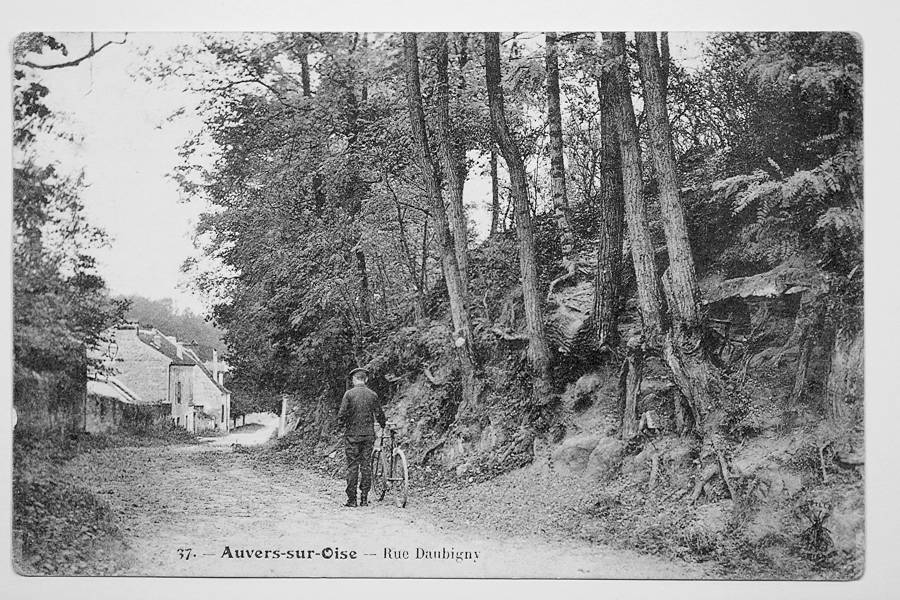

VINCENT VAN GOGH (1853-1890)

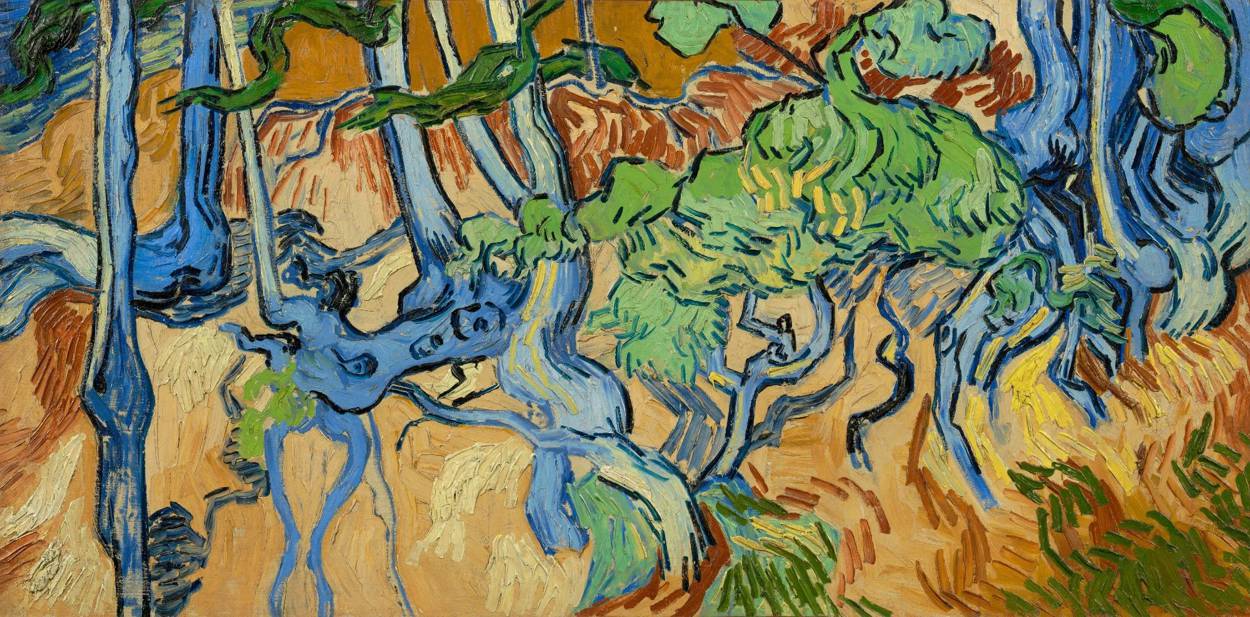

'Tree Roots', 1890

(oil on canvas)

VINCENT VAN GOGH (1853-1890)

Post card ‘rue Daubigny, Auvers-sur-Oise’ in which the painting ‘Tree Roots’ (1890) by Van Gogh was recognised, 1900-1910,

©arthénon

You can drag the arrows across the postcard to compare the overlapping image of Van Gogh's painting to the original scene.

For many years it was thought that 'Wheatfield with Crows' was Van Gogh's last painting, but we now have evidence to the contrary. In 2012, Louis van Tilborgh, a senior researcher at the Van Gogh Museum, discovered documentation that pointed to another painting as his final work. Van Tilborgh uncovered an article from 1893 by Van Gogh's brother-in-law, Andries Bonger, who wrote that 'the morning before his death he had painted an underwood, full of sun and life'. Further investigation pointed to Van Gogh's painting of 'Tree Roots' as the more plausible, though less symbolic candidate for this distinction.

To add to the story, Wouter van der Veen, the scientific director of the Institut van Gogh, was researching 'Tree Roots' during the Coronavirus lockdown in 2020, when he discovered a postcard that depicted a cyclist standing on Rue Daubigny alongside an embankment of exposed tree roots. He recognised the location which was only a couple of minutes’ walk from the inn where Van Gogh died, and realised that the configuration of roots corresponded to those in the painting. After the site was carefully cleared of its overgrowth and studied by Dr. Bert Maes, a specialist in dendrology (the science of trees), it was deemed 'highly plausible that this is the location where 'Tree Roots' by Van Gogh was painted'.

Wouter van der Veen has written a book outlining his research and, in respect for those who were risking their lives and caring for the sick during the Covid-19 pandemic, decided to make his book available as a free download to all who wish to read it. You can download it here, 'Attacked at the very root: An investigation into Van Gogh's last days'.

Our illustration shows the postcard where Wouter van der Veen spotted the similarity in the root structures. You can drag the arrows across the postcard to compare the overlapping image of Van Gogh's painting to the original scene.

'Tree Roots' was a final developmental leap for Van Gogh. He drops his viewpoint to exclude the conventional arrangement of foreground, mid-ground and background, to concentrate his attention on the movement of organic forms across the picture plane. There is no fixed point of focus; just an overall pattern of blue trunks and roots with green foliage against an ochre and brown embankment. The painting is at once both realistic and abstract, observational and stylized. When you look at it in the context of painting over the next fifty years, you see how its form resonates in many artworks along the path from representation to abstraction.

It is a painful paradox that, hours before his suicide, Van Gogh was immersed in the creative mindset that produced a work as exhilarating and innovative as 'Tree Roots'. His tortuous mood swings, from the euphoric 'highs' of artistic achievement to the desperate 'lows' of melancholy were increasing with age. The gaps between them were also diminishing, reducing his ability to work and the self-belief that provided. How he managed to create so many sublime images, with a mind that was frayed by emotional instability, speaks volumes of his courage in communicating his unique visionary insights that open our eyes to the extraordinary experience of his everyday world.

Van Gogh Timeline

VINCENT VAN GOGH (1853-1890)

Photograph of the artist (1872) aged 19.

Vincent van Gogh died on 29th July 1890, aged 37. In 1880, at the age of 27, he decided to become an artist. Over the next 10 years he produced around 1,100 drawings and 900 paintings, the best of which were done in the last two years of his life as his style matured. He was largely self taught and not greatly appreciated in his own time, but his originality was recognised by subsequent generations and is now considered one of the most influential and popular artists in Western art.

-

1853 - Van Gogh is born in Groot Zundert, a small town in the south of Holland

-

1869 - Starts work as a clerk for the art dealers, Goupil and Co. in the Hague.

-

1873 - He is transferred to the London branch of Goupil's.

-

1875 - He is dismissed from his job and returns home.

-

1876 - Works as an unpaid supply teacher in London and later as an assistant to a Methodist minister. Returns home for Christmas and works in a bookshop in Dordrecht.

-

1877 - Starts to study Theology with a view to following his father into the religious life but fails his exam.

-

1879 - Moves to the Borinage, a poor coal mining district in Belgium to work as an evangelical missionary.

-

1880 - After a mental breakdown in the Borinage, he decides to become an artist. Theo begins to support him financially.

-

1882 - Sets up a studio in the Hague.

-

1883 - Returns to live with his parents in Nuenen and begins to draw and paint the rural workers.

-

1885 - His father dies in March and later he paints his first major work 'The Potato Eaters'.

-

1886 - Moves to Paris where he is influenced by the Impressionists.

-

1887 - Paints over 15 self-portraits, including 'Self-Portrait with Grey Felt Hat'. Starts to show the influence of Japanese woodblock prints in his work.

-

1888 - Moves to Arles and tries to establish an artists' community with Paul Gauguin which proves disastrous. Paints the 'Yellow House' and seven versions of 'Sunflowers'.

-

1889 - After his breakdown in Arles, he voluntarily admits himself to St Paul's Asylum in St. Rémy. Paints 'Irises', 'Starry Night' and 'Self Portrait: Saint-Rémy'.

-

1890 - Moves to Auvers where he paints panoramic landscapes such as 'Wheatfield and Crows'. On 27th July, he paints his final work, 'Tree Roots', and later in the day shoots himself in the chest. Two days later, he dies from the wound.

-1889.jpg)